Manufacturing in the City

The Brooklyn Navy Yard

First came the recession and then Superstorm Sandy, for most of its history, the Brooklyn-based countertop maker IceStone has been recovering from some disaster.

“Manufacturing is a tough thing to be doing anywhere in America, but particularly in an urban city,” says Dal LaMagna, its CEO. “Most of the work that is done here is paper pushing, not actually making things,” he admits.

In 2016, there were 78,800 people in manufacturing jobs in New York City. It represents a slight growth from last year, but still, pales in comparison with the 158,600 employed in 2001.

To curb the shrinking of manufacturing, since 2006 the City created 20 so-called industrial business zones (IBZ) in already existing industrial areas all in the outer boroughs.

IceStone, which makes $1.5 million worth of sustainable countertops a year, is one of about 330 businesses based in the IBZ at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Since the 300-acre area is owned by the city, its tenants escape real estate pressures that are an additional recent challenge for manufacturers in other IBZs. Private property owners tend to prefer the development of hotels and mini-storage facilities rather than industrial spaces.

The original purpose of industrial business zones was to create “safe havens” against residential development, says Adam Friedman, executive director of the Pratt Center for the Community Development. “But it is not adequate for today’s real estate pressures from other commercial uses,” he says.

Even when these pressures are absent, the high-cost environment of New York City becomes an ultimate test for companies’ business models.

Constant recovery

IceStone was founded in 2003 by Brooklyn entrepreneurs Miranda Magagnini and Peter Strugatz who bought a struggling factory at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. LaMagna became one of the company’s first investors because he was interested in companies making an impact: in this case, IceStone countertops use post-industrial glass that would otherwise end up in a landfill.

For the first several years the company struggled with quality, discarding a lot of countertops that they made. By the time IceStone settled on a sustainable countertop formula that worked it was 2008, in the midst of the recession. “So [we] were able to make it now, but [we] weren’t able to sell it,” LaMagna recalls.

The business was burning cash, he says. The co-founders left the company and LaMagna stepped in as CEO in 2011. By that time, IceStone had lost $27 million dollars.

The company cut its production costs, reduced the number of employees, and was on track to have a profitable model, when disaster struck again: this time, not by the economy, but the forces of nature. Sandy flooded the factory floor with all the machinery, and the company was almost back to square one.

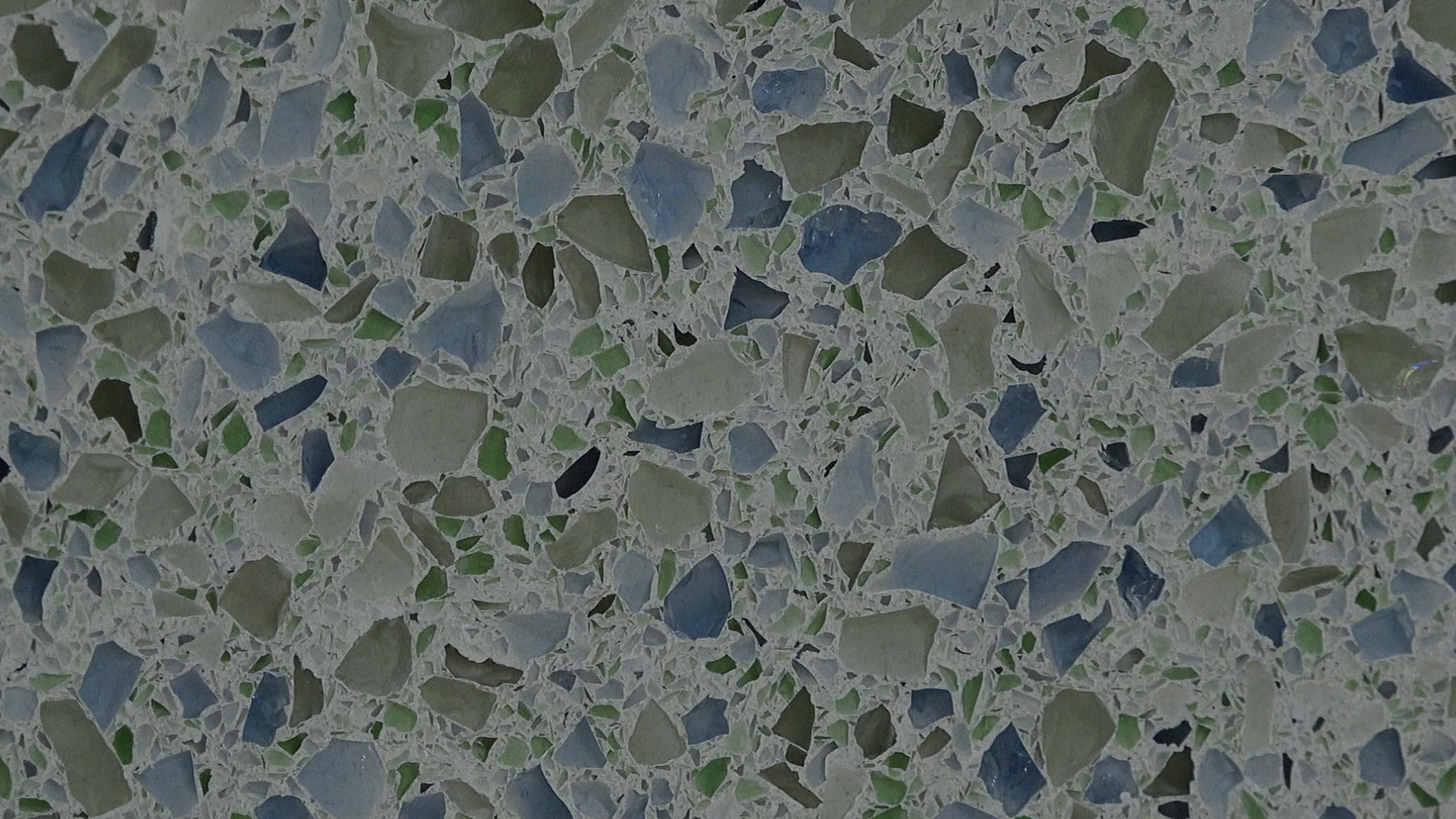

IceStone uses post-industrial glass to make countertops

LaMagna admits that the question of whether the company should stay in New York came up. “You would think that we would move, but we decided not to. This is such a complex factory with a lot of equipment that took more than 10 years to set up. We are here because it’s been set up here already.”

Friedman, who also is on the board of directors of the Brooklyn Navy Yard, argues that manufacturers can benefit from being in New York City if they use a highly skilled creative workforce and make custom-made items, production of which their New York-based clients want to oversee.

“I am not sure IceStone falls into this category,” he says. “Of course, we want to keep them here, the question is, of course, is there a good business rationale for them to stay here.”

Access to identity

Businesses that produce standardized products tend to leave the New York. Last winter, Sweet’N’Low, artificial sweetener manufacturer, closed their packaging facility at the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

Sweet’N’Low artificial sweetener used to be packaged at the Brooklyn Navy Yard

“They were putting chemicals in little paper packets. You could do that anywhere in the world. They really didn’t need to be close to downtown Manhattan. This loss is tragic in a way, but the truth is the space is going to be occupied by other manufacturing companies,” Friedman says.

The Brooklyn Navy Yard has a long waiting list of companies wanting to move in. In addition to location, the Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corporation, a not-for-profit entity that runs it, gives businesses access to their services, such as help in finding grants.

“Places like Industry City and the Brooklyn Navy Yard, Brooklyn Army Terminal, they give you access to technology and expertise. They give you extra services, such as access to capital and reduced rents. They give you address; they give you identity. All those things are really important,” says Charles Euchner, senior researcher at the Center for an Urban Future, a think tank that studies trends of New York City.

New York City’s future in manufacturing “is undoubtedly with small firms that operate in niche markets and take advantage of modern production processes,” Euchner wrote in his report titled “Making It Here,” published in July.

When the average number of workers in manufacturing firms is just 13.4 (compared to 26.3 in New York State), the culture of sharing that forms in such industrial spaces, as the Brooklyn Navy Yard, becomes essential.

Access to these services is something that a lot of businesses want. However, at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, and other IBZs there is not enough vacant space left, Friedman claims.

“There are some vacant properties, but they tend to be very small, and it is a little misleading to consider them vacant. There may not be a building on them, but they are used for truck parking, or storage of materials,” he admits.

Pressure from hotels

Industrial Business Zones were an invention of the Bloomberg administration. However, Michael Bloomberg himself didn’t always favor manufacturing in the City.

“New York City should not waste its time with manufacturing,“ he said in his 2003 interview with the Financial Times. “If you are a pharmaceutical company or a steel company, you do not need to be here.”

This was an odd thing to say for a mayor of a city that historically has had many steel companies, Friedman notes.

Moreover, by the mid-2000s, it became evident that this attitude is not doing the city any good, advocates argue. Residential development was pushing real estate prices in historically industrial areas through the roof, and, with manufacturers moving out, the pool of industrial jobs was shrinking.

The creation of industrial business zones has eased the pressure from residential development, but today the main challenge comes from commercial development.

“This is a different type of displacement, it’s a different type of gentrification,” Friedman explains. “If you were a factory owner going out today to try and find space, it will be extraordinarily difficult because the property, even though it is designated for manufacturing can be used for other things.”

This is explains why there is less and less manufacturing left today in the small industrial business zone around Kent Avenue in Williamsburg. Across the street from the Brooklyn Brewery, in a historic cooperage building is now the popular Wythe Hotel that has inspired the opening of many bars and nightclubs in the area.

Thinking that the property can be converted to something more profitable than a manufacturing facility, many owners are pricing it accordingly, Friedman says. The issue became so pressing that in 2015 Mayor Bill de Blasio introduced a measure that requires special permits for the development of hotels in industrial business zones.

Soon, the Williamsburg industrial business zone will even have an office building also despite that the IBZ regulation specifically prohibits it. In July, the City Council approved the plan to build an eight-story office building at 25 Kent Avenue. The project developers promised to give a fraction of the space to light manufacturing.

The area around it will be recognized as an “Enhanced Business Zone,” a new type of zoning that can be expanded in the future to other industrial areas in Brooklyn.

“It’s really not an industrial business zone at this point in time,” Friedman concludes.

–by Olga Slobodchikova