Failing the GED and the Homeless in New York City

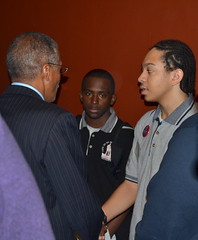

PHOTO BY KRISTEN KIRALY: Shamel Quiles (left) and Tyler Smith (center) advocate for the educational rights of homeless students. Here they are speaking with shelter and school professionals about the impact of homelessness on education. They are both on track to graduate high school.

The homeless population in New York City is growing each year. Half of all homeless parents have not earned their high school diploma, limiting them at best to low-wage, dead-end jobs. The GED exam should be a tool in helping them achieve self-sufficiency, but it is not. New York City has one of the worst GED passage rates in the country.

“If you miss your education during childhood, you’ll be poor and homeless,” says Dr. Ralph da Costa Nunez, president of the Institute for Children, Poverty, and Homelessness. “If you want to deal with this problem, put a GED program in every shelter. Not only do you leave a shelter with a home, you leave with a degree and a better opportunity to go to college and to work.”

With the most recent economic downturn, those without a GED lost their jobs at double the rate of people with the degree, and more than ten times the rate of college graduates. With the unemployment rate continuing to hover around nine percent in New York City, an education is crucial in obtaining and maintaining jobs.

The GED passage rate in New York is the second worst in the country, followed only by the District of Columbia. In 2007, New York was ranked higher than Alabama and Mississippi, but both states have since fixed their flawed systems.

There are 2.8 million people in New York that have not earned a high school diploma. However, less than 2 percent sit for the GED each year. In New York City, the passage rate for those who take the five-part exam is 48 percent, compared to the national state average of almost 73.

Policymakers in New York have yet to target and address the problematic GED passage rates. In 2014, the GED Testing Service will launch a new GED. The national exam will be more difficult to better test for college readiness, which could mean even lower passage rates in New York.

The State Department of Education acknowledges that “the most significant factor in determining student success on the GED Test is preparation.” Across the state 67 percent of people who take the GED do not participate in a preparatory course.

Iowa has one of the highest GED passage rates in the country, consistently hovering in the mid-90th percentile. Iowa also has an intensive preparation system where students are pre-tested, tutored in all problematic areas and then given a GED practice test, all before sitting for the actual exam.

“There are a lot of people who are not finishing high school for a variety of reasons, some personal, psychosocial, or academic, and they aspire to get a GED in lieu of a traditional high school diploma,” says Sarah Brannen, policy director at the Center for an Urban Future and author of the report “Failing the Test.” “Unfortunately, a good portion of the people leaving the New York City high school system is not prepared to sit for the test.”

The four types of GED prep programs in the city are run by the New York Department of Education, community-based organizations, the City University of New York, or public libraries. There are no formal GED programs in New York City shelters, only sporadic classes run by volunteers.

The problem is that there are no statewide requirements. The programs throughout New York City maintain different goals and various approaches to preparing their students. Of the few who pass the GED nationally, 43 percent enter an institution of postsecondary education. However, only 11.6 percent successfully graduate. In New York City, most drop out within the first few semesters.

The programs that succeed in New York City are those that focus on the GED as a stepping-stone to gain acceptance into college. CUNY Prep, a GED program in New York City, falls into this category of “bridge programs.”

Various agencies from New York City, including the City Council and the Department of Education, have created the website www.GEDCOMPASS.org to inform New Yorkers about the GED exam.

“Bridge programs that offer GED prep but also basic skill development dependent on the student’s need are a newer model that people are talking about,” says Brannen. “The problem is that these intensive programs require funding that the state and city really don’t have.”

State funding for the GED was $3.9 million in 2007-2008. The budget has been cut by almost 40 percent in just a couple of years. For 2010-2011, the apportionment of funds for the GED was $2.4 million.

New York City allocates about $1,000 to support an individual in a GED preparatory course. However, the cost of programs that promote college readiness is much more. CUNY Prep is funded by the Center for Economic Opportunity, with $10,000 to $12,000 being spent on each student that completes the program.

The new GED exam launching in 2014 will likely cost more for the city to administer. In 2011, the New York Board of Regents suggested that the state begin charging test takers a fee as a way to discourage unprepared individuals from walking in. With the possibility of higher costs in 2014, this discussion remains ongoing.

PHOTO BY KRISTEN KIRALY: Quiles and Smith speaking with shelter and school professionals about the impact of homelessness on education. There are 66,000 homeless students in New York City public schools, but only 40% will graduate. The GED must be an option for the 60%.

“There is some debate as to what is going to happen in 2014,” says Brannen. “An increased cost has made people in the state and city feel very nervous because resources are already very tight and added cost would leave us in a worse situation.”

One of the groups that will suffer the greatest from added fees is also the most vulnerable: the homeless population of New York City. Nunez argues that what the city does not spend now on these struggling students it will end up paying for later in the form of social programs for the poor.

“The GED is not going to solve the problem of being homeless; alone it is not extremely valuable,” says Nunez. “But it should be the first step to community college and then continuity with education, shooting up to a Bachelor of Arts degree or a high tech vocational school.”

For the full story, please visit kristenkiraly.com.