Stories

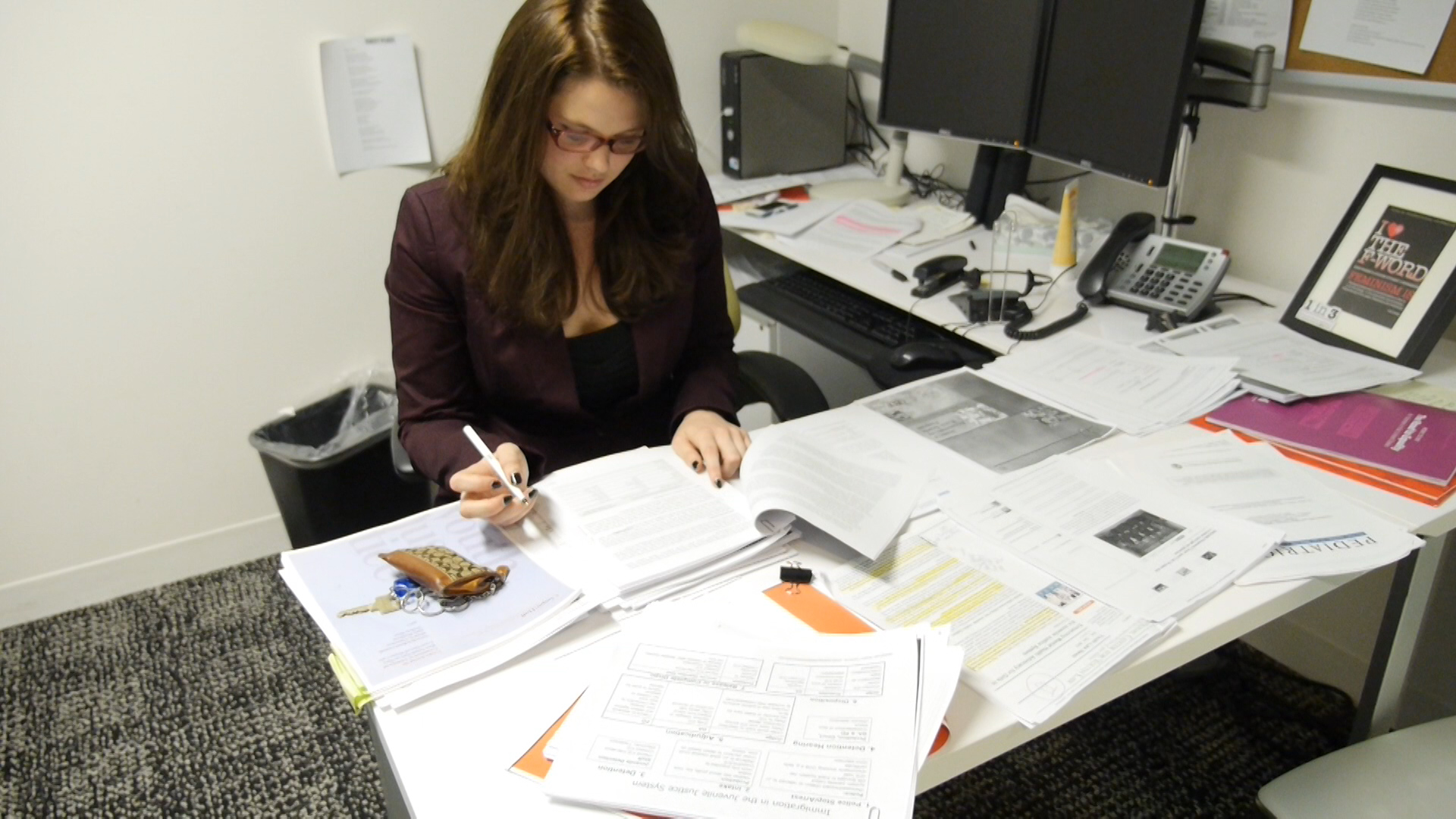

When Sara Hernández (name has been changed) entered foster care in New York City at age 14, she was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. She entered the system after school administrators discovered her diary, in which she wrote about suffering from abuse.

“Being in care, you’re moving back and forth, that becomes overwhelming,” said Hernández. “Then you don’t have the right people around you, you don’t have that love and affection.” While in foster care, Hernández was additionally diagnosed with depression and an eating disorder.

In the United States, children in foster care experience higher rates of health issues, from physical to mental and behavioral, than any other group of children. Most of these medical conditions are chronic, under-diagnosed and under-treated, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics. At the national level, policy-driven opportunities under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) are arising, and at the local level, community initiatives are being implemented, to better address the unique health needs of this population. Girls and young women in the foster care system, especially, stand to gain from these new opportunities.

“Girls are not prioritized, especially poor girls,” said Lindsay Rosenthal, Fellow at the Ms. Foundation for Women in New York City. Her fellowship work, in part, aims to leverage the nation’s new health care law to inspire community-based solutions to better serve girls in foster care. “Girls in foster care are the most marginalized in our country,” said Rosenthal. “They are overwhelmingly very poor, they are also overwhelmingly girls of color.”

In New York City, over 13,000 young people are currently in foster care. Evenly split between males and females, black and Hispanics are largely over-represented among this population. In Harlem, foster care placement rates are over double the citywide average. In the neighborhood of Central Harlem, 73 percent of children in care are black. In East Harlem, 33 percent are Hispanic, while 55 percent are black. In a community where health outcomes are already poor and rates of chronic illness are high among the general population, efforts to address the health disparities these children face are crucial.

While race, economic class and gender are all factors that play a role in health access and health outcomes in the U.S., the reasons children in foster care enter the system, and their experiences while in the system, present a whole other set of challenges to accessing continuous, comprehensive, and appropriate health care.

“I had like seven or six therapists,” said Hernández, running through a mental list of names, as she counted them each out on her finger tips. Her seven years in the foster care system from age 14 to 21 included four different foster care agencies and over 15 different placements in neighborhoods across the city, including Harlem.

“Trust was a big problem for me,” Hernández said. “The more I was treated like crap, the more I couldn’t trust anybody, or open up to them. I was moving around so much that I would end up seeing a new therapist. I would have to tell my story over again. And then one of the biggest problems was that the paperwork always wasn’t right. I just always felt that I had to basically come out, scream, and say, ‘This is me. This is who I am’.”

Constant placement, caseworker and agency changes, based on a child’s evolving needs, placement vacancies and experiences within a placement, can mean a disruption in health care for the child. Medical records and knowledge of the patient’s history can suffer from lack of coordination and communication among the different parties involved.

Abuse, abandonment, or neglect — the reasons foster cases are commonly opened — may also prevent a child in care from trusting an adult enough to share their health needs. These factors create barriers to continuous, quality and appropriate medical services for young people in foster care. For young women and girls in the system, these factors have significant implications when it comes to reproductive health care and services.

“I think a lot of foster care is pride swallowing,” said 21-year-old Imani Brammer, who has been in foster care in New York City since the age of 16. “It’s pride swallowing to even announce that you are in foster care and then you have to swallow your pride again to go to a caseworker and say, ‘Hey, I have a pregnancy scare,’ or ‘Hey, I think I may have an STD.’ Just asking where to go to see a GYN is going to provoke looks and questions.”

In New York City, the rate of pregnancy for girls in foster is double the citywide teen pregnancy rate. A 2005 report from the city’s Public Advocate Office estimated that one in every six girls in care is either pregnant or parenting. The report recommended that the NYC Administration for Children’s Services (ACS), which governs the city’s foster care system, strengthen sex education programs for all adolescents in care.

“I never got any reproductive health lesson from foster care,” said Brammer, a journalism student who explored the subject of reproductive health care and sex education for girls in foster care as a writer for Represent, a magazine for young people in care. “Once something happens, if you have a pregnancy scare, or if you just want to get a checkup, you have to pursue it yourself, and in that instant is when they would tell you. I don’t think it should be like that, because sometimes, you don’t want to wait until it’s too late to have to find out these things.”

Hernández, on the other hand, did receive sexual education while in care from behavioral specialists or other adults, depending on her placement. However, even when sexual education services are available, they can be ineffective in addressing the underlying reasons why girls in foster care may become pregnant, whether intended or unintended, and how they feel once they are pregnant. Girls who were taken away from their families and put into care may have specific motivations for starting new families of their own, according to advocates and researchers.

Hernández recalled a conversation she had with a friend who was also in care. The friend told Hernández she wanted to have a baby. Hernández questioned why she would want to become a mother at such a young age and the friend replied that it was because she felt alone. “A lot of kids end up having kids at an early age, because they feel lonely,” Hernández explained. “A lot of us have low self-esteem. And it was hard for her to provide for this kid, but she just wanted that love from somebody.”

Girls in foster care also experience higher rates of sex trafficking, forced prostitution and sexual abuse than the general population, which occurs both before and during their stay in foster care. Over 70 percent of children and teens who enter foster care in the U.S. have been physically abused and neglected, and/or sexually abused, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics. This factors into their specific reproductive health care needs.

“Becoming pregnant can be a way of reasserting autonomy and control over their own body,” Rosenthal explained. “And re-purposing their body into something that is healthy and positive, rather than something that is for violence and abuse, and coercion and exploitation.”

Pauline Gordon is the New York City Regional Youth Partner for the youth advocacy and service network, YOUTH POWER! “I think a lot of it has to do with trauma,” Gordon said of the high pregnancy rates among girls in foster care. Gordon, who spent five of her own seven years in foster care in Harlem, where she now lives after aging out of the system, explains that mental health care and reproductive health care services must be coordinated in order to better serve these girls. “Many girls in foster care have been victims of sexual abuse and many don’t address it. We need more trauma-focused therapy.”

In Gordon’s Harlem community, there are already examples of coordination among medical providers that serve kids in care. The Helen B. Atkinson Health Center (HBA) on W. 115th street is a part of the Community Health Network (CHN), a system of 11 federally qualified health centers in New York City that provide health care for undeserved populations with federal, state and grant funding. For HBA, this includes a direct relationship with foster care agencies, like the nearby Lutheran Social Service of New York, and taking some patient referrals from the Administration for Children’s Services.

The community health center offers patients a variety of services across various fields of medicine, within one coordinated network and all under one roof. “It really is sort of a one-stop-shop for them to get everything that they need to get and get it in a very quality way,” said Center Director Lissa Southerland.

For girls in care, the communication between a psychiatrist or therapist, a pediatrician, and an OB/GYN can help her achieve more comprehensive care. At HBA, medical practitioners not only coordinate amongst themselves, but with staff social workers and educators, as well.

HBA also caters their services to the specific concerns of their adolescent patients. “We try to create a very safe space for them when they come here and try to make it as comfortable as possible,” said Southerland, “so that they will open up and talk to us about whatever is going on, so that they can get the care that they need.”

One of the ways HBA does this is with their open-access model for adolescent patients. “We don’t turn teens away at all,” Southerland explained. “We will see them on the day that they come. They don’t need to make an appointment. They can walk in. If they need any sort of family planning or reproductive health services — birth control, pregnancy tests, STD screening, HIV testing — we see them right on site.”

Once teen patients finish their visit with the medical provider, they go and see the on-site health educator. “The health educator may be able to tease out any other issues that may be going on that they may not have been able to talk about with their provider,” Southerland explained. The provider and educator consult with each other in order to gain a more holistic picture of the patient’s needs.

On a national level, the Affordable Care Act presents new opportunities to regulate and systematize coordinated and continuous health services for kids in foster care under its Medicaid reforms. Young people in foster care are beneficiaries of Medicaid, government health insurance for low-income and otherwise qualified Americans. The health care law includes the advent of Medicaid health homes, coordinated networks that provide comprehensive health and social services. The ACA gives states the option to establish these centers of integrated and holistic care, with the help of federal funding, for Medicaid patients with chronic and mental health conditions.

The Community Healthcare Network (CHN) leads and co-leads Medicaid health home networks across New York City under the New York State Department of Health. Under CHN, medical providers at Harlem’s Helen B. Atkinson Health Center refer patients to Medicaid health homes. HBA also helps manage care services, with an on-site patient navigator, for patients already enrolled in health homes.

A 2013 report by the Medicaid Institute at United Hospital Fund investigated how participation in these health homes might impact the lives of young people in foster care. The report suggested that New York City and state policy could be enacted to require that health plans for those in foster care — the majority of whom have chronic and/or mental health conditions — contract with Medicaid health homes. The report recommended that new health homes could be created with a pediatric patient population in mind, or that existing health homes be adapted to serve children and adolescents, in addition to adults.

More specifically, Rosenthal sees the potential the health homes have to bring continuous reproductive care to the chaotic lives of girls in foster care. “Moving from placement to placement,” she explained, “that disruption has a huge impact on their emotional well-being, their mental health, on all kinds of things, but especially in terms of reproductive health care. It’s going to disrupt any access that they had to birth control, or a supportive adult who they knew they could trust for having concerns related to their sexual health or reproductive health.”

Under a Medicaid health home, a girl in foster care could maintain her established relationship with her same team of providers, regardless of placement changes. “That is a huge paradigm shift,” said Rosenthal. “It’s a huge opportunity for girls in foster care and we’re very excited about it.”

Hernández has aged out of the foster care system, but plans to work in youth advocacy with this specific population. She likes the idea of health homes for kids in foster care. “I honestly feel like that’s the best way to go. Then we could just be ourselves and not have to repeat our stories over and over again.”

Health Care for Young People in Foster Care from Contessa Gayles on Vimeo.