Stories

Kitaab Club from Ali Withers on Vimeo.

Bay Ridge, in Brooklyn, is home to a new population of Arabic-speaking kids who aren't getting enough English language learning through the public schools, so an outside group has stepped in

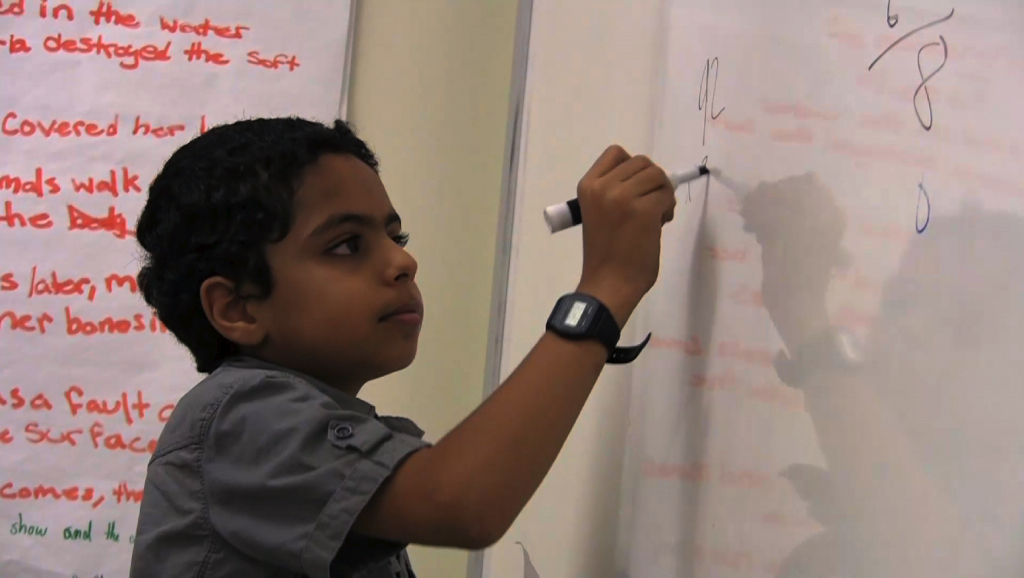

BAY RIDGE, BROOKLYN – Just as the school bell dismisses students from PS/IS 30 in Brooklyn, a new cluster of boys and girls gather under the main overhang. As current students stream past, one young girl in a hijab with a Dora the Explorer backpack walks quietly up with her mother, and a couple older boys dart in, chatting in Arabic. They’re filed nearly into line and marched back into the school for the next part of their day: homework club.

The kids zig-zag around the tutors as they make their way to a fourth-floor elementary classroom, where they pull out small folders of worksheets and story books tucked into Ziploc bags. Evelyn Garcia, the 23-year-old coordinator of this program, Kitaab Club, weaves between the stubby tables and chairs.

“Did you bring your homework today,” she asks one of the boys. He grins at her and his friends.

“I don’t have any homework!” he yells, teasingly.

She hears this a lot. Eventually, she wrangles him into a seat, with a mixture of coaxing and firm tones, and partners off the thirty other six- to twelve-year-olds with volunteer tutors, most from the nearby Fort Hamilton high school, who help the kids complete their homework in math and English, or do extra practice worksheets with them.

“For the most part, the kids come ready to do their homework,” Garcia says. “Except for some who don’t bring it, or forget parts of it.”

Kitaab (or book in Arabic) Club, offered for free by the Arab American Association of New York (AAANY), whose offices are one avenue away from the Bay Ridge school, is one of the emerging answers to assisting kids of Arab-descent access better English-language learning, both on and off the school clock.

The kids in Kitaab are, for the most part, Egyptian, Algerian, Yemeni, and Lebanese, which is representative of the neighbourhood. Bay Ridge, a once Italian-Scandinavian area of south Brooklyn is now home to the densest Arab-American population in the city and the highest population of Arabic-speaking students, which the Department of Education terms “English Language Learner” (ELL).

Being an Arab-descent ELL in Bay Ridge gives most students the same option it does to 77 percent of all New York City English learners: English as a Second Language (ESL) class.

For those who start young, this might amount to a couple years until they reach proficiency. But middle- and high-school Arabic-speaking students, who are much more likely to be new not just to English, but to America, can find themselves scraping through the regular curriculum with three half-hour segments of ESL per week.

“Unfortunately, I don’t think that there’s adequate resources allocated for ESL students,” said Garcia, at an interview in the AAANY office. “Most [new immigrant] students can’t really speak English, so they’re pretty much lost throughout the day.”

The largest elementary school in the neighborhood, PS 102, with 1360 students and 100 Arabic-speaking families, has a common stand-alone ESL program, where kids are pulled out of class by aptitude.

“It’s a challenge with some kids,” said Margaret Sheri, the Parent Coordinator. “If kids come in at fourth and fifth grade, it’s harder to catch up.”

Even though students are grouped by ability, they are not grouped by linguistic background. Arabic-speaking kids find themselves learning English alongside those with mother tongues in Russian, Chinese, and most commonly for New York: Spanish.

Throughout the rest of School District 20, which encompasses other ethnically diverse neighbourhoods like Sunset Park, Bensonhurst, Dyker Heights, and Ocean Parkway, other methods are offered, like Transitional Bilingual Education (TBE), where the curriculum is taught in their mother tongue, or a Dual Language program, where material is taught in English and another language on alternating days, and the children – taken evenly from the two linguistic backgrounds – are expected to become fluent in both.

Less than a fifth of English learners in all boroughs are placed in a TBE track, and only four percent into Dual Language, most of them in Manhattan. The relative fewness of these programs is partly the Department’s mandate, and partly the parental unawareness. Normally, requests for intensive language programs must come from 12 sets of parents at a given school.

“If the parents are recent immigrants, they don’t speak [English] and they are not aware that this is something the can do,” noted Garcia. “They just put [their kids] in ESL classes instead of asking for a bilingual program.

Though there are no bilingual tracks in Arabic, the Department recently announced 29 new Dual Language programs, which accepted their first cohorts in September. Amongst them, was an Arabic-English program for PS/IS 30 Mary White Ovington. It’s not just a first for the school, but a first for the city.

It was their Principal, Carol Heeraman, who noticed that over fifty percent of her ESL students were of Arab descent, and initiated the process for a dual language program at the school.

The present cohort is limited to two kindergarten classes, confirmed an administrator at the school office, with the intention of adding grades as their classes graduate upwards through the years.

Heeraman turned to the AAANY for endorsement and to partner for after-school programs, like Kitaab club.

“It’s kind of a pilot program,” said Linda Sarsour, the Executive Director of the AAANY. “I’m hoping that if they see it’s beneficial to the community and really providing dual language education, that it continues to expand in the area.”

Sarsour said the program was popular with parents, and the waiting lists were jammed by mid-summer.

Educators and community leaders alike have all recognized the added challenge to helping students through their assignments if there’s a communication barrier with the parents. According to a community survey conducted by the AAANY and NYU’s Graduate School of Public Service in Bay Ridge 64 per cent of adult respondents said interpretation and translation would be helpful for all their paperwork concerns.

Sheri, the parent coordinator, said her office sends out information to the Arabic families in their language and has a couple bilingual staff members to help. The Department also provides oral or over-the-phone interpretation services for teachers who need to talk to parents, and translated standard paperwork in 15 of the most common languages.

“Schools have to provide for parents needs,” said Maryann Polesinelli, Director for ELL for District 75, devoted to Special Education, which works closely in ELL programs for students with learning disabilities.“You want to see how [schools] are integrating families, and how they see families as partners in their children’s education.”

Garcia has also seen how communication barriers have a big impact on some of her students.

“We had a first-grader who was an English Language Learner, and the issue with her is that she never brings her homework because she leaves it at school,” she said. “There’s a miscommunication. She can’t understand what is expected of her from her teacher, who can’t tell her or her parents in Arabic what to do, so she’s struggling a lot.”

At Kitaab when this happens, the tutors flip through a thick binder of worksheets of word-searches, spelling exercises or math problems. Sometimes they’ll find a book to read, or if the kid really can’t focus that day, they’ll play dominos.

But the kids are less fortunate in ESL class. Ellen Driesen, the District 20 Representative of the United Federation of Teachers, explained that teachers are pushing for proficiency to keep students ontop of curriculum material, which is becoming increasingly more demanding with the national Common Core Curriculum standards that went into effect in New York this year.

“If you’re coming into a new culture, being in a class of 32 is a killer. And then you’re being pulled out for ESL and you’re expected to keep up to the Common Core,” said Driesen.“There needs to be an awareness of what you’re asking kids to do.”

Garcia and the other Kitaab volunteers have grown accustomed to some students walking in feeling defeated and frustrated.

“There should be resources allocated to these students to make these students successful, and to meet the high expectations that schools and educations keep piling on them,” she said.

Driesen and educators hope that with the new New York mayor, Bill de Blasio, taking office in 2014, there will be a new direction for public education and more attention for ELLs. In the meantime, Kitaab is also planning to expand, creating new places for students on a waiting list.

“We have a lot of students who want to do good,” said Garcia. “They want the help.”