Bird Mania

More New Yorkers are taking up birding amid the pandemic. Produced by Sydney Bertun and Serge Kharytonau.

Watching Bird Migration can Reduce your COVID-19 Stress

By Serge Kharytonau

The COVID-19 pandemic has been stressful and tiring for many. It has changed the ways we work, communicate, travel, and most importantly how we experience this stress. New Yorkers have been forced to rethink the ways they deal with anxiety as millions of bedrooms and living rooms have been turned into offices.

A Canada goose spotted in Brooklyn

While some New Yorkers had a chance to build their own gyms at home, or get bicycles for outdoor rides (with some niche stores profiting up to 600 percent from what they made last year), others chose a cheap way to let off steam: birding.

There are more than 300 species of birds that can be spotted in New York City. They are not just beautiful creatures. Scientists say that birds can have a direct positive impact on your mental health.

The relaxing effect of birding could be one of the reasons this hobby has remained popular in America since the late 1880s. According to the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, approximately 46.7 million people observed wild birds “around the home and on trips” in 2011. Although the number of birdwatching enthusiasts fell nationwide by 2 million people in the next five years, it seems like birding community is again on the rise in 2020 as people seek more outdoor activities.

Michele, member of the Brooklyn Bird Club.

Michele moved to New York City from North Carolina a few years ago. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, she has been working as a personal assistant to a globally-renowned cinema director. At the time of the spring lockdown, she chose to leave her office, and return to her family. There, one of her acquaintances invited her on birding walks with a pair of binoculars.

Michele has enjoyed watching birds for a long time. Soon after moving to North Carolina, she has realized the pandemic was a good reason to restart the hobby that she liked so much.

“I already knew about birding a few years ago. But then this past spring during the pandemic I decided to pursue it even more because I had time, and time outside, and I’ve been doing it ever since.”

In mid-July, Michele returned to New York City, and became involved with professional birding walks with Brooklyn Bird Club, which she joined recently. The club was founded in 1909, and is today one of the oldest acting birdwatch groups in North America. This year, the club grew from 100 to over 300 members because of the pandemic. For many people like Michele, birding became a great source of safe in-person socializing.

“It’s kind of like a quite hobby. You can do it safely during the pandemic. Its not like a contact sport or like something when you need to be within six feet of somebody,” Michele said. “I think it brings a lot of peace.”

A Northern Harrier on a tree

New York City is located along a unique natural “bird highway”, the Atlantic Flyway. It is a major migratory route of birds. The Atlantic Flyway stretches from the tropical areas of South America towards Greenland.

Every year, millions of birds follow this path for their spring and fall migration and many of them land in New York City for a while. In search of safe green locations, birds usually stay for short breaks in major city parks. This is where birds feel safe and get enough food and water before they continue their journey.

Central Park, Palham Bay Park, Jamaica Bay Wildlife Refuge, Green-Wood Cemetery, and Prospect Park are particularly popular among birders: they offer the greatest variety of migrating species. However, there are plenty of smaller birdwatching spots in local parks within each of the five boroughs. Visiting one of those is a good idea to avoid long commutes.

Kathy Willens, member of the Brooklyn Bird Club

“During the pandemic people need things to relax, ways to distress. And birding is one of those perfect pursuits,” said Kathy Willens, an Associated Press photographer and birding veteran with three decades of experience. In her opinion, birding has become a great source of safe human communication during the pandemic for both freshly-introduced and mature birders.

“Right now it’s a very relaxing pursuit. People need that during the pandemic. And I did too. I’ve found so many new birders.”

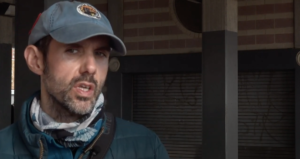

Dennis Hrehowsik, who was elected president of Brooklyn Birding Club in late 2017, noticed that after the pandemic started, birding became a popular way to escape the indoors: “People sought, especially in NYC, activities that they can do in a park. And birding became one of these activities.”

Dennis Hrehowsik, president of the Brooklyn Bird Club

Since birding has become a technology-savvy industry, an amateur birder now uses smartphone applications like iBird, Audubon, or Sibley to help identify birds.

“When I began birding it was really hard to find information besides a field guide that wasn’t passed down person to person. Now I can go online and within about three minutes I can find different solutions to different ID problems from a dozen people,” – said Hrehowsik.

Since March 2020, public interest for birding apps and websites have grown exponentially. Prior to the pandemic, the world’s biggest birding community, eBird, had an average participation growth rate of approximately 20 percent year over year. In March-June 2020, eBird membership grew by around 70 percent (compared to 2019) with almost 200,000 new members.

Bird identification app Merlin ID doubled the number of downloads compared to 2019. Cornell Lab of Ornithology (that runs both eBird and Merlin ID) announced that its identification app had achieved the largest monthly increase in its six-year history – reaching 150,000 new downloads in April 2020.

Another popular app, Audubon Society’s Bird Guide, achieved similar results as the number of installs doubled in March-April 2020 compared to the same period in 2019.

Although anyone can do birding on their own, the exciting part of it, for both beginners and veterans alike during the pandemic, is the ability to interact with other people in fresh air. The pandemic has become a turning point for people who had interest in birding but didn’t get involved on a professional level.

Diana Quick and her camera

Since the COVID-19 outbreak in New York, Diana Quick has come to picturesque Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn to do birdwatching four to five times a week. Quick was involved in amateur birding for many years.

But the pandemic has become a turning point in her relationship with birds. Quick, who has been in nonprofit communications for more than 20 years, recently purchased a 600 mm professional photography lens to get better images of Baltimore orioles, bald eagles, and other “cooperative” birds that she meets during her walks.

Quick photographs birds for her Instagram account. Although she does not yet plan to turn her social media profile into a source of income, she is glad to observe how her interest turned into a passion:

“I’ve been interested for a couple of years, but this year since the pandemic, I’ve had a bit more time to be able to come and I’ve learnt a lot during the last 8 months,” she said. “It’s new, but it’s definitely a passion now. And I think it would be a lifetime passion.”

What More Birdwatchers Could Mean for Conservation Policy

By Sydney Bertun

Michele in Prospect Park.

It’s an early fall morning in Prospect Park. Joggers and strollers share the paths at this time of day, and it’s quiet for New York, save for the occasional biker with a boombox. Michele, a production assistant, is here too.

She walks with a set of binoculars around her neck, eyes cast upward to witness the fall migration. She pauses every so often, noting a bird in her phone. Michele is a “pandemic birder,” or one of the many New Yorkers who have taken up the hobby since March.

“I think it brings a sense of peace,” she said of her new hobby. “There is a sense of wonder that comes with watching birds.”

Michele is typical of many new birders in that she started on her own, but eventually joined a local club. While a lot of information is available online, organizations like the Brooklyn Bird Club are continuing to provide an essential background education. According to the club’s president Dennis Hrehowsik, their membership has increased by 30 percent over the past seven months.

“It’s kind of like learning a language,” he said. “You can’t learn Mandarin just listening to tapes, you have to go to Beijing at some point and interact with people.”

Dennis Hrehowsik and a group of birders on Coney Island.

In many ways birding is the perfect socially distant activity: it’s outdoors, it’s easy to do alone or in a masked group walk, and there are endless ways to learn more about the hobby through apps and books. But the growing interest in birdwatching could have a meaningful impact beyond binocular sales.

Along with increases in fundraising (see video story), more bird watchers means higher bird counts through eBird and NestWatch, two crowdsourcing sites run through the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. The sites have had a 29 percent and 41 percent increase respectively over the past year. The impact of this data could help to shape environmental policy across the country in years to come.

There is actually historical precedent to support this. Citizen-gathered data sets for birds predate the apps and websites birdwatchers use today. The National Audubon Society began its annual Christmas Bird Count in 1900, which ornithologist Frank M. Chapman proposed in response to declining bird populations. The event began with 27 counters in that first year, and has grown to include more than 30,000 participants worldwide according to National Geographic.

In part due to the work of those early Christmas Bird Counts, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act was signed into law by Woodrow Wilson in 1918. While it initially included one treaty with Canada, the law has been updated several times to include new agreements with Mexico, Japan and Russia which protect migratory bird species.

The Christmas Bird Count has continued to be relevant for policymakers on the federal level. In the 1980s, the United States Department of Agriculture launched a program to protect American Black Ducks after their decline was shown in CBC data.

More recently, in 2012, the Environmental Protection Agency cited CBC data as one of 26 indicators of climate change. However, under the Trump Administration, the EPA removed all information about climate change from it’s website.

In lieu of support from the executive branch, the Christmas Bird Count has become even more critical for conservationists. The Audubon Society now produces a yearly Common Birds Decline report from the data, and works with lawmakers to support climate change prevention policies like clean energy tax credits.

While the Christmas Bird Count has been cancelled this year due to the COVID-19 pandemic, increased count numbers through eBird, the online bird tracker run by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology may help to fill some of the gap.

Kathy Willens marks a bird in her phone.

Since it was launched in 2002, eBird has gone through several iterations and is now accessible through a phone app for bird watchers to count with. The data is compiled monthly, and made publicly available via request. According to Jenna Curtis, a project leader for engagement and outreach at the Cornell Lab, there are a wide range of beneficiaries.

“Everyone uses eBird data,” she said. “From students doing science fair projects, to photographers, to government agencies, nonprofits, and statewide conservation organizations.”

Like the Christmas Bird Count, eBird has been a valuable tool for conservationists. In 2018, the State of California approved Endangered Species Act protections for Tricolored Blackbirds based on eBird data, which showed a 34 percent decline in population over a 10 year period.

Other policy initiatives that have come out of eBird data include the “Lights Out” campaign in Dallas, where downtown buildings shut off their lights on days when large numbers of birds are migrating through.

On the federal level, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) uses eBird counts of Bald Eagles to issue permits for wind power projects. According to Curtis, the data set allows USFWS to identify areas of population of high or low “abundance.” Wind projects are only approved in areas with low numbers of eagles to prevent further population decline under the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act.

While it’s difficult to predict exactly what policies could come out of increased counts over the pandemic, Curtis says there is no doubt that it will be useful.

“More data is always a good thing,” she said. “I tell people, even if you log something from your backyard, you’re probably the only one logging a bird there, and that fills a data gap.”

Of the many species that the Cornell Lab of Ornithology tracks, Curtis says the Bobolink is of particular concern because it faces threats on multiple fronts. Bobolinks “breed in open areas across the Northern United States and Canada,” according to the Cornell Lab. Due to habitat loss, they now also breed in eastern hayfields and meadows.

After migrating, the Bobolinks winter in the southern interior of South America. A recent study found that the birds rely on rice fields for food in their wintering grounds, which can contain deadly pesticides.

Because of these dual threats to Bobolink habitat and food supply, they were placed on the 2016 State of North America’s Birds Watchlist, which “includes bird species that are most at risk of extinction without significant conservation actions to reverse declines and reduce threats” according to the Cornell Lab.

The Bobolink is just one of 432 species on the North American Birds Watchlist, or 37 percent of the total species which migrate through the continent. It is difficult to articulate the full impact of these declines, because of the interdependent nature of ecosystems.

Birds are vital pieces of the puzzle. They help to control pests, pollinate flowers and regenerate forests. Their absence signals permanent changes to ecosystems.

While conservationists have been ringing alarm bells for years now, critics say regulations negatively impact American business. In November of this year, the Trump administration moved to roll back protections for birds, which would “greatly limit federal authority to prosecute industries for practices that kill migratory birds,” under the 1918 Migratory Bird Treaty Act according to ABC.

In light of all this, the increased eBird data over the pandemic in combination with new enthusiasm for birding could help make the case for restoring the 125 environmental protections that have been weakened over the last four years once President-elect Biden takes office.

Biden has already committed to rejoining the Paris Climate Accord, and to end new fossil fuel permits on federal lands and waters. These would be significant first steps, climate change being the “single greatest threat to birds,” according to the National Audubon Society.

Experienced birdwatchers like Hreohwsik, president of the Brooklyn Bird Club, recognize that this hobby is about more than just identifying species.

“It’s not really about the gulls,” said Hrehowsik, on a recent group walk. “This is really a walking advertisement for taking care of Coney Island, and taking care of the environment.”