Video produced by Kelsey Doyle and Goldie Poll

Active Design + Active Programs = Better Health for Everyone

New York City Residents “Shape Up” at a free aerobic class held at the Tony Dapolitio Recreation Center, a center that has been revitalized to house a plethora of exercise programs.

NEW YORK CITY— Active design is being implemented across New York City’s landscape in order to combat obesity and integrate physical activity into the daily lives of New York City’s residents. Yet, the active design movement alone may not be enough to launch a lifestyle change for everyone, especially low-income communities.

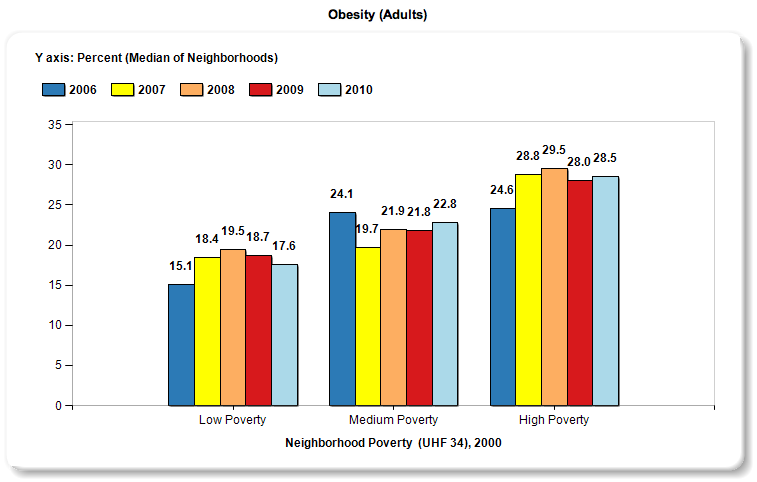

Neighborhoods with high poverty rates, such as Morrisania in the Bronx and Jamaica in Queens, are areas also hindered by the highest obesity rates in New York City along with the corresponding health issues obesity can bring. More than sixty-two percent of residents in the Bronx are overweight or obese, higher than the rate in any of New York City’s other four boroughs. In comparison, in Manhattan, just over forty-two percent of residents are overweight, the lowest percentage in the city. These low-income neighborhoods have the most to benefit from Mayor Bill de Blasio’s Community Parks Initiative (CPI)—an initiative to build a more inclusive and equitable park system via active design guidelines—yet it is going to take more than contemporary playgrounds to get these neighborhoods on track.

The Parks department argues the main issue lies not in the amount of innovative green space available, but in the infrastructure and programs offered at these spaces.

“Public space is built around communities. The most successful parks or the most affluent parks just have a relationship with public space. I used to think design was the most important, but the way you design a space isn’t what really attracts people to that space,” said Elizabeth Bowler, Northeast Program Manager at the National Parks Conservation Association. Bowler has previously worked with New York City’s Department of Parks and Recreation as a crew manager for environmental education, forest restoration, and tree stewardship programs in Harlem and the Bronx.

“What really brings people is the element of programming. Not until you have a need for programs, then will you get people to be invested in the space. You have to tell people about it; it just can’t be there. Community groups that have a lot of pull, they engage kids through their strong presence. As much as parks should be recreational, we are trying to give young people skills.”

According to research from University of California, Berkeley, the University of Michigan, and Griffith University on urban green space, public health, and environmental justice, “geographic access alone may not fully capture the impact of parks on physical activity or obesity. Usage may depend on park characteristics and programs offered.” Programming is key to ensure that these innovative architectural feats are utilized.

Public parks, playgrounds, recreation blacktops, and green spaces in or near the heart of the city already have a well-established infrastructure and programming. Awareness of the yoga classes, maps of bicycle paths, schedules of morning jogging groups, sign up sheets for forest restoration programs are easy to find in Central Park. As one of the top ten tourist attractions and primary destinations in New York City, Central Park receives constant attention to the accessibility of its programs and these programs are what generate awareness. That’s not to say that Manhattan does not also benefit from active design and additional green space. The more innovative space in any neighborhood, no mater the socio-economic conditions the better to promote physical activity, psychological well being, and the general public health of urban residents. However, that level of attention is not necessarily the same across the rest of the city’s 1,700 parks, playgrounds, and recreation facilities.

“The places where the obesity epidemic is the most devastating are typically low income communities and those are more likely to be urban communities. This is an equity issue, an environmental justice issue, and this is why we really have to focus on low-income communities,” said Professor Kristen Day, who specializes in issues of design and health at NYU Polytechnic School of Engineering. “Some of the strategies are the same for middle income communities, but at the most basic and fundamental levels, in low-income areas you want people to be active by choice.”

The CPI aims to re-create 35 parks in fifty-five neighborhoods across the city’s five boroughs, reaching approximately 220,000 New Yorkers living within a 10-minute walk of the targeted parks. While Mayor de Blasio’s $170 million plan has taken a major step in the right direction to promote physical activity in marginalized communities through active design.

Kirsten Sibilia is a partner at Dattner Architects, a New York City based architecture firm that focuses on designing civil and public architecture. The firm dates back fifty years and is responsible for designing the first “adventure playgrounds” in Central Park—setting the tone for the way its architects currently approach open space and urban design.

“As much interaction as we can get between people and the built-in environment is our goal. Places, especially like the south Bronx, where the obesity and asthma rates are high, we really seek out these opportunities and feel good about participating. A lot of agencies in New York that are responsible for big funding are looking for opportunities like these,” she said.

The Parks and Recreation Department currently runs thirty-five recreation centers that offer aquatics, exercise classes, and after-school programs for the residents of New York City. Yet, their programs do not stop there. New and old spaces, unaffiliated with the department are constantly being sought out and repurposed for a multitude of programs. “No matter how interactively appealing a playground or stairwell may be, throwing a basketball out on a blacktop isn’t going to work,” said Chief of Staff Paul Fontana, who oversees the Recreation department, the largest of the three branches. The majority of recreation centers in New York City were formerly bathhouses making their large open space is ideal for basketball courts, dodge ball, and dance programs. “It’s only twenty-five dollars a year for a membership, so it is very affordable for people with very tight incomes…You don’t get eucalyptus scented towels like at Equinox, but its practically free,” said Fontana.

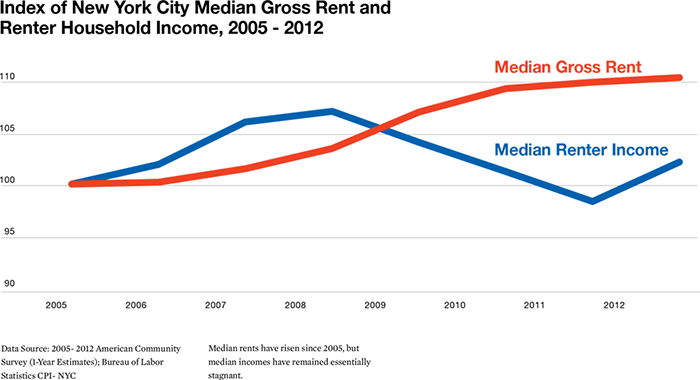

Some argue that New York City’s ongoing struggle for enough affordable housing is one of the biggest obstacles to active living. According to the NYC Bureau of Fiscal and Budget Studies, the supply of rental apartments affordable to working families making less than $40,000 a year is rapidly evaporating.

“First of all, people really can’t afford gym memberships. That’s why there are programs. Second of all, there aren’t many places for people to go,” said Nancy Bruning, a Physical Activity Specialist in Public Health who teaches community fitness classes wherever she can find a space to use.

According to the latest census data, the annual median income for the 229 households living in the most worst section (Morrisania) of the most neglected neighborhood (southwest Bronx) is $8,694 and the federal income poverty level is under $18,000 for a family of three. Affordability of programs is a major concern. The city has tried to address affordable programming through its thirty-five recreation centers. The Tony Dapolito Recreation Center in lower Manhattan is one of the recreation centers throughout the city that runs a myriad of affordable successful programs. Even though this recreation center is located in Manhattan, residents come from all over to use the center because of its extensive programing.

Fontana hopes that the centers will continue to be redesigned for multi-use. Currently the Tony Dapolito has over 7,000 active members. New sites for recreation centers are being sought after.

Free programs, outside of recreation memberships, such as Shape Up NYC or Walk NYC, are also all over the city. If the space is not available for the designated activity, organizers use partner facilities, such as hospitals and schools. Demand for programs like Shape Up are also dictating active design of new facilities and the renovation of old. New Yorkers can track the projects through the Parks Department’s Capital Project Tracker—an online, searchable tool that allows residents to learn more about projects in design, procurement, and construction.

“It depends on the day of course, but people come,” said Coleen, a Shape Up cardio teacher at the Tony Dapolito center. “But you gotta’ be consistent, you gotta’ follow up on it, that’s what I found.”

~ By Kelsey Doyle