Educators fight stigma, provide support as HIV increasingly affects older adults

by Jenise Morgan

Karol Markosky wants to talk about safer sex with older New Yorkers and their caregivers. In a culture that too often doesn’t acknowledge sexuality in later life, she feels she is “fighting stigma on the front lines.”

As special programs manager for New York City’s Council of Senior Centers and Services (CSCS), Markosky develops and leads workshops for healthcare and aging service providers on HIV prevention, how to address depression and co-morbidities in HIV-positive elders and other related themes. In collaboration with other organizations, CSCS’s HIV/AIDS and Older Adults Training and Technical Assistance Program, now in its sixth year, also provides direct education to older adults on safer sex.

The Center for Disease Control (CDC) estimates that by 2015 half of people infected with HIV in the United States will be over 50 years old. But the statistic doesn’t simply reflect advancements in treatment and care for those already living with the virus. One sixth of new HIV cases are individuals over 50, according to the AIDS Community Research Initiative of America (ACRIA).

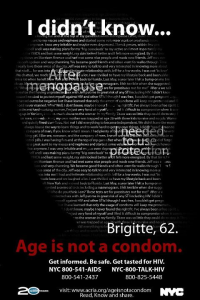

ACRIA, which has worked on HIV and aging for many years and published the widely-cited “Research on Older Adults with HIV” study in 2006, created a series of social messaging campaigns in response to the increase. Launched in April 2012, the agency’s “Age is not a Condom” campaign includes advertisements in New York City bus shelters and a website on which older adults can share their experiences.

Images courtesy of ACRIA

Luis Scaccabarrozzi, director of ACRIA’s HIV Health Literacy Program, says the stories reflect riskier behavior than one might expect. “As much as sex doesn’t stop after 50, I think [there are] a lot of substance abuse and mental health issues that haven’t been resolved after many years,” he says in a phone interview.

For heterosexual elders who watched the AIDS epidemic unfold, contracting HIV may seem like someone else’s problem. “Most of HIV prevention is really about identifying yourself as at-risk,” says Markosky. “If you’ve never identified as at-risk then what’s going to push you to protect yourself or get tested? Nothing.”

While New York state law requires healthcare professionals to offer HIV testing to people aged 13 to 64, no such provision exists for older individuals. The CDC does recommend that practitioners advise people over 64 to take an HIV test if they engage in high-risk behavior, such as having unprotected sex.

Amongst older women, for whom unintended pregnancy is no longer a concern, this scenario is prevalent. In the 2012 National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior study, released by Indiana University’s Center for Sexual Health Promotion, only 7.4 percent of women over 61 reported using condoms the last ten times they had vaginal intercourse.

“Not all seniors will negotiate condom usage,” says Markosky, who often fields questions from women who want to become intimate with a new male partner.

Believing that “providers and patients are unable to reliably estimate HIV risk in older patients,” the American Academy of HIV Medicine now suggests that screenings be offered to all adults.

“I think healthcare providers need to be raising the issue of HIV with everybody, but it’s a special challenge with older women,” says Joan Garrity, a founding member of the Sexuality and Aging Consortium at Widener University.

“There’s an assumption that older women become asexual,” she adds.

Today, women of all ages account for one in three New Yorkers living with HIV, according to the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Post-menopausal women are at particular risk for HIV infection because of physical changes, such as thinning of the vaginal walls.

Jane P. Fowler learned of her HIV-positive status in 1991. Previously married for 23-years, she had become intimate with a longtime friend. “[I]n those days, I knew little about HIV/AIDS, only that a mysterious, fatal ailment was affecting the gay community,” Fowler wrote in a 2003 article for “Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes”. “It didn’t occur to me that I would put myself at risk by engaging in […] unprotected sex.”

Fowler, a retired Kansas City Star reporter, learned she was HIV positive through a routine blood exam at the age of 50. After several years of depression and isolation, the retired Fowler started, at her son’s insistence, to speak out and educate other older women in 1995. “He said, ‘You’re positive. Now do something positive,’” she says.

Now in her 70s, Fowler spearheads HIV Wisdom for Older Women and gives talks around the country. She reminds her female audiences that the only HIV status they can be certain of is their own, and has specific advice for older gentlemen.

“I always tell men, ‘if you can get it up, cover it up,’” says Fowler.

The sense of loneliness Fowler experienced after her diagnosis is common. For older women recently infected by or living with HIV, support groups play a vital role in combating isolation. “It’s a stigmatized disease,” says Dorcas Baker, a site coordinator at Johns Hopkins University Hospital and co-founder of Older Women Embracing Life (OWEL). “It’s like, ‘Grandma, how’d this happen to you?’”

OWEL (“Oh Well, I’m older and have HIV but I’m living”) meets monthly at two churches in Baltimore and Washington, DC. Carolyn Massey, who serves as the organization’s executive director and is HIV positive herself, says that spirituality plays a major role in handling an HIV diagnosis and disseminating information about the virus. “We know from the research that when you start talking about older [African-American] individuals, about half of those affected by HIV considered themselves to have a faith home,” she says.

Forbes Magazine recently reported that 90 percent of women living with HIV in DC “are black, with the burden falling mainly on heterosexual women.”

In 2009 new HIV infections occurred in black women 15 times more than in white women, according to the CDC.

Massey acknowledges the heightened challenge that faces HIV-positive women who may also be concerned with poverty, family issues and other chronic illnesses. “Every person has some burden, some trials, some challenges. And usually we have more than one in tow. HIV, unfortunately, is something that is here. It’s not going away. It’s manageable and preventable, but you have to do the work,” she says.

Related Stories: