Building a Bridge Between Immigrants and America

By Samyu Sridhar

As we sat in her Sunset Park office, director of Muslims Giving Back Yamina Kezadri thought back to her own father’s immigration story. He left a civil war-torn Algeria for America in 1993, leaving the two-and-a-half year-old Kezadri, his wife, and his other child behind. They would later join him in 1998, but in their absence, he found America to be an unforgiving environment for an immigrant.

“The places that he went to were always the masjids,” said Kezadri, “to seek shelter, to sleep and to, you know, feel safe.” Kezadri sees her father in the newly arrived immigrants that come to Muslims Giving Back seeking help, and she feels galvanized to do everything she can for them. “Just like my father has had the chance to survive, to make it, to bring me to this world, I want to make sure that I do it right for everyone.”

Muslim Community Center prayer space and shelter. Photo by Samyu Sridhar.

Many people who have immigrated to the United States do not have family or a support system here. Without community, and with minimal knowledge of the language and infrastructure, life here can be isolating and tremendously difficult to navigate.

Faith-based organizations in New York are attempting to foster that sense of community through human connection. Newly-arrived immigrants are facing a slew of systemic challenges, including unstable housing situations, lack of work, slow bureaucratic processes, and legal and medical vulnerability. Many don’t have access to the individualized help that is necessary to navigate these challenges; that’s where faith-based organizations are stepping in.

Anthony Pérez, a longtime immigration rights activist and a leading organizer in the migrant outreach efforts at St. Francis of Assisi Roman Catholic Church in Koreatown, envisions a system to help immigrants fully integrate into American society. “That’s where a lot of the nonprofits and churches are seeing that there is a need to fill,” said Pérez. “The need for them to apply for asylum, and to educate them on what the process is and how it can be helpful for them.”

St. Francis of Assisi Roman Catholic Church. Photo by Samyu Sridhar.

Pérez’s own faith is a strong motivator for his work in advocacy and grassroots organizing. He re-engaged with his Catholic faith in 2010, and the St. Francis church was integral in welcoming him back into Roman Catholicism. He wants his work and his lifestyle to represent the ways of St. Francis, and he wants to lead by example. “I’m one of those Catholics that realizes that it’s not just about evangelizing,” said Pérez. “It’s about praying while you walk, not staying in the temple and praying.”

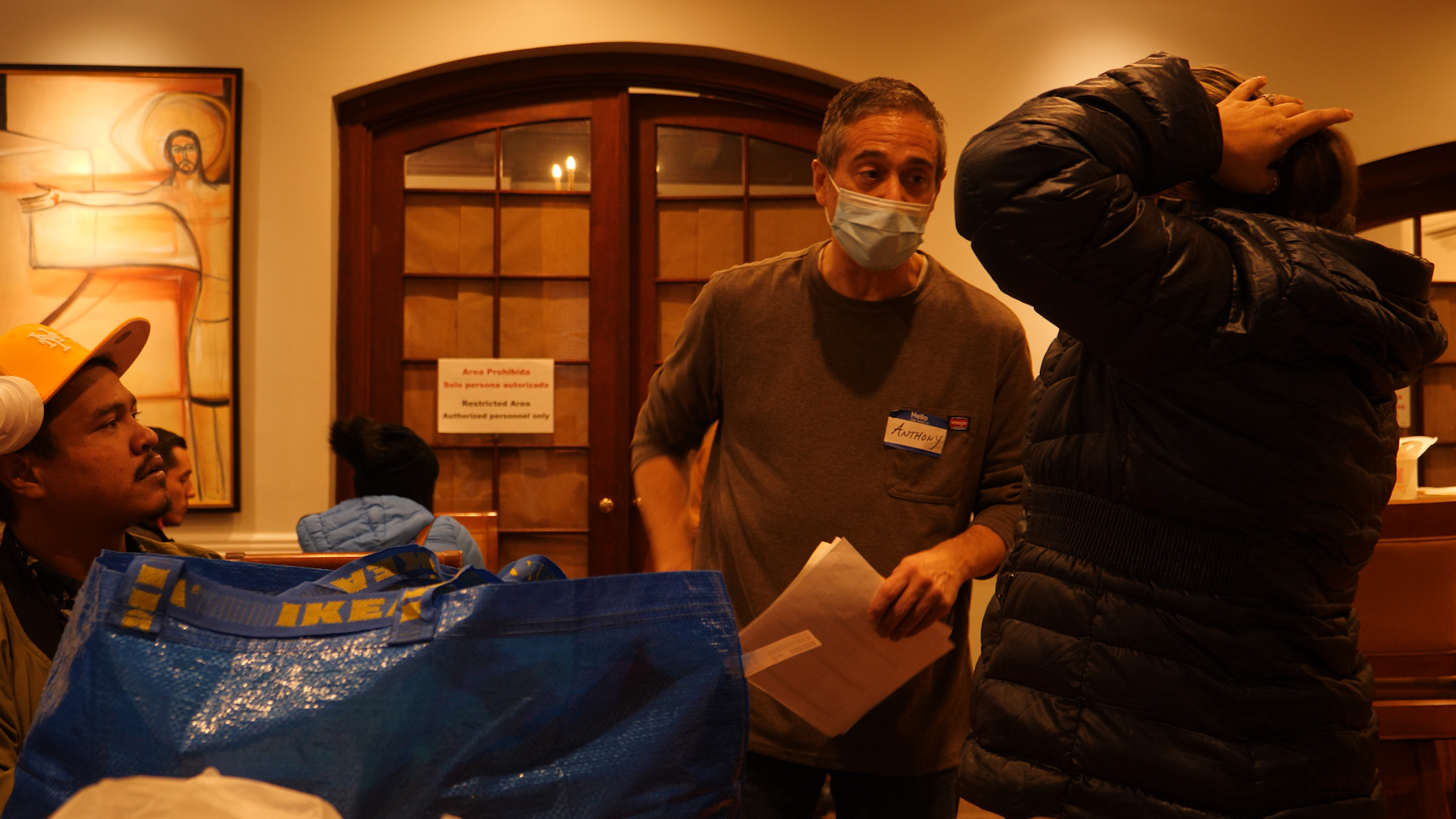

Anthony Pérez explaining forms to two immigrants. Photo by Samyu Sridhar.

Pérez, who has organized for Faith in New York and lobbied on behalf of DACA recipients, feels that it will be necessary in the coming months to “push City Hall hard.” Pérez said that the city government may be well-intentioned, but they just can’t afford to fill vacancies for certain initiatives due to a lack of funding. “In that kind of atmosphere, we know that to be able to provide services for this group of immigrants, we’re going to have to push politically.”

The preliminary 2023 budget for the Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs allots $50.8 million for “key immigrant services,” including IDNYC, ActionNYC, and the Adult Literacy initiative. This number is less than 1% of the city’s total budget and $21.6 million less than the adopted 2022 budget. ActionNYC, a legal services program, and Adult Literacy Initiative, an ESL education program, are both outsourced to a network of community-based organizations affiliated with MOIA, some of which are faith-based.

Though these governmental measures are in place, immigrants are still getting lost in the processes behind these measures. The months-long process of waiting for deportation cases to be heard in order to obtain a work permit leaves a large gap of unsupported time in which immigrants cannot work; many don’t even have access to adequate legal aid. According to the Vera Institute, 60% of non-detained immigrants with a legal defense win their cases as compared to a 17% success rate without a legal defense.

“You can’t press pause on a human being’s life,” said Kezadri.

St. Francis Church’s website says that the migrant center is “inspired by the Franciscan tradition of ministering to people who are alienated, displaced, or persecuted.” Led by Friar Julian Jagudilla and Pérez, the migrant center has taken up Mayor Adams’s call to action by hosting clothing and food donation centers three times a week.

During the clothing drives, Pérez calls asylum seekers waiting in the pews of the church into another room, where he and other volunteers assess their forms and pull from a treasure trove of donated clothes to match their requests. The storage rooms of the church are filled with racks of clothing, organized by gender, size, and age, as well as toiletries and essentials for infants, such as diapers. These items are mostly donated and funded by the members of the church.

Donated clothing storage room. Photo by Samyu Sridhar.

Pérez and Jagudilla have taken their efforts one step further by beginning to meet with migrants to better understand their needs. “At present, the assistance that we’re providing is just hope, and some material needs like food and clothing assistance,” said Pérez. “We are telling them that we are welcoming them, we are inviting them to community events here at St. Francis, and we are just getting some organizing off the ground.”

In those one-on-one meetings, Pérez hears peoples’ personal complaints and creates a plan to address them. Just last week, Pérez had a number of people alert him to the possibility of a hasty eviction from the Stewart Hotel, one of the sites that was chosen to house immigrants following the closing of Mayor Adams’s “tent city” due to upcoming cold weather. They may have to uproot their lives yet again to move to a less accessible area of New York.

“[The immigrants] were in a state of panic because they were being told that they needed to sign some kind of documentation, and be prepared to move at a moment’s notice,” said Pérez. The timeline of these complaints aligns with the announcement of the transition from the Stewart Hotel as an NYC Department of Social Services emergency shelter to a Humanitarian Emergency Response and Relief Center.

“Some of them were feeling intimidated and powerless, and just not knowing what their rights are, were signing it, thinking that they had no say in whether they could stay or they were to be moved,” Pérez added.

Similarly at Muslims Giving Back, Kezadri has been receiving immigrants who have had challenging experiences within the NYC shelter system. Shelters are overcrowded, dilapidated, and prone to violence, and they are not equipped to handle the rising influx of people. “A lot of people are coming back to complain and saying, ‘I don’t feel safe, I don’t feel comfortable, I don’t feel good,’” said Kezadri. “They’re unable to practice, they’re unable to do what they need to do to live.”

Kezadri has been with Muslims Giving Back, an organization that practices “faith in action,” for 10 years; she is now the director, and she oversees every step of the integration process for immigrants. Muslims Giving Back, in collaboration with the attached Muslim Community Center, shelters immigrants in their masjid, provides English classes, holds meal services, facilitates job and apartment placement, helps secure legal aid, and invites new immigrants to join prayer services.

Kezadri is deeply motivated by the core Islamic belief of serving one’s community. Community is an all-encompassing term in Islam; the Quran states that one should “show kindness to parents, and to kindred, and orphans, and the needy, and to the neighbor that is a kinsman and the neighbor that is a stranger, and the companion by your side, and the wayfarer, and those whom your right hand possess.”

“For me, in Islam, that’s the predominant definition, to be peaceful, to serve,” said Kezadri. “When we heard about the migrants coming in through Port Authority, we felt like, ok, what’s going on, what do they need, how can we serve them?”

Muslims Giving Back has a warehouse of food stock and a large, bare-bones space, but they are running almost entirely on donations from and fundraising by the masjid community. Currently at capacity, their resources are stretched very thin. “Unfortunately with what’s happening with COVID, post-pandemic, and now the financial crisis that’s happening, those community members that we’ve been relying on for so long are unable to provide,” said Kezadri.

Food storage room at Muslims Giving Back. Photo by Samyu Sridhar.

Muslims Giving Back has not yet received any funding from the city budget. Kezadri fears that there is an inequitable distribution of resources among different groups of immigrants, and that Muslim immigrants are not a priority. “It’s just politics, and if a certain group doesn’t fit into certain politics, then your priority just basically falls,” said Kezadri.

Charlie Davidson is trying to combat these inequities through advocacy. As the co-chair of Synagogue Coalition on the Refugee and Immigration Crisis, a volunteer-led organization, his goal is to educate the communities within the synagogue coalition to actively participate in political demonstrations and direct service for all immigrant and refugee communities. “Everything that everyone does everywhere is incredibly short-term and reactive, because there isn’t a bipartisan leadership that’s going to cause a rational immigration policy to emerge,” said Davidson.

Motivated by their religious beliefs and their historical experience of oppression, as is stated on their website, the SCRIC has run donation drives, raised funds for resettlement of refugees in New York, and sponsored workshops on the legal and administrative aspects of the immigration process, among other things.

St. Francis Church, Muslims Giving Back, and SCRIC all came to a consensus on what the administration needs to do at the very least: make clear what resources are available to immigrants and that they know their rights. “Before we can tap into those resources, we need to be informed of what those resources are,” said Kezadri.

The passion and determination organizations like St. Francis Church’s migrant center, Muslims Giving Back, and SCRIC are bringing to this humanitarian crisis has been a godsend for people who might have otherwise fallen through the gap.

Viviana Flores had been in the U.S. for 15 days after traveling from Colombia; she was staying in a hotel on 44th street in Manhattan, where her son was sick with a respiratory virus and her husband was injured. St. Francis Church was her first stop. “They have helped us a lot with finding doctors,” said Flores.

For Flores, attending mass was a family affair; she would gather her loved ones and go to church every Sunday. She continues to lean on her faith even as she arrived in the U.S., hoping to attend mass with her family again. “It’s very beautiful,” Flores said of faith and Catholicism. “My soul is strengthened by my faith, which in turn works to solve my problems.”

Three months ago, Mamadou Diallo left Senegal in search of better work in order to provide for his family. He now works in the Muslim Community Center, helping to organize and tidy the masjid and welcome people in for prayer. “Here, Alhamdulillah, [Muslim Community Center] received me. My family is here in MCC. It’s your house, your family. Muslim all is one family.”

Kezadri encourages the immigrants to eat together, pray together, and make friends with one another. She invites members of the masjid community to come socialize with and mentor the newcomers because she believes that community integration is vital to ensuring the immigrants’ long-term well-being and independence in this country. “This is their way to link themselves to their roots,” said Kezadri. “This is their way to feel a sense of rapport and connection.”

Women grouping together for Jummah prayer in the Muslim Community Center. Photo by Samyu Sridhar.