Building a Bridge Between Immigrants and America

By Samyu Sridhar

As we sat in her Sunset Park office, director of Muslims Giving Back Yamina Kezadri thought back to her own father’s immigration story. He left a civil war-torn Algeria for America in 1993, leaving the two-and-a-half year-old Kezadri, his wife, and his other child behind. They would later join him in 1998, but in their absence, he found America to be an unforgiving environment for an immigrant.

“The places that he went to were always the masjids,” said Kezadri, “to seek shelter, to sleep and to, you know, feel safe.” Kezadri sees her father in the newly arrived immigrants that come to Muslims Giving Back seeking help, and she feels galvanized to do everything she can for them. “Just like my father has had the chance to survive, to make it, to bring me to this world, I want to make sure that I do it right for everyone.”

Muslim Community Center prayer space and shelter. Photo by Samyu Sridhar.

Many people who have immigrated to the United States do not have family or a support system here. Without community, and with minimal knowledge of the language and infrastructure, life here can be isolating and tremendously difficult to navigate.

Faith-based organizations in New York are attempting to foster that sense of community through human connection. Newly-arrived immigrants are facing a slew of systemic challenges, including unstable housing situations, lack of work, slow bureaucratic processes, and legal and medical vulnerability. Many don’t have access to the individualized help that is necessary to navigate these challenges; that’s where faith-based organizations are stepping in.

Anthony Pérez, a longtime immigration rights activist and a leading organizer in the migrant outreach efforts at St. Francis of Assisi Roman Catholic Church in Koreatown, envisions a system to help immigrants fully integrate into American society. “That’s where a lot of the nonprofits and churches are seeing that there is a need to fill,” said Pérez. “The need for them to apply for asylum, and to educate them on what the process is and how it can be helpful for them.”

St. Francis of Assisi Roman Catholic Church. Photo by Samyu Sridhar.

Pérez’s own faith is a strong motivator for his work in advocacy and grassroots organizing. He re-engaged with his Catholic faith in 2010, and the St. Francis church was integral in welcoming him back into Roman Catholicism. He wants his work and his lifestyle to represent the ways of St. Francis, and he wants to lead by example. “I’m one of those Catholics that realizes that it’s not just about evangelizing,” said Pérez. “It’s about praying while you walk, not staying in the temple and praying.”

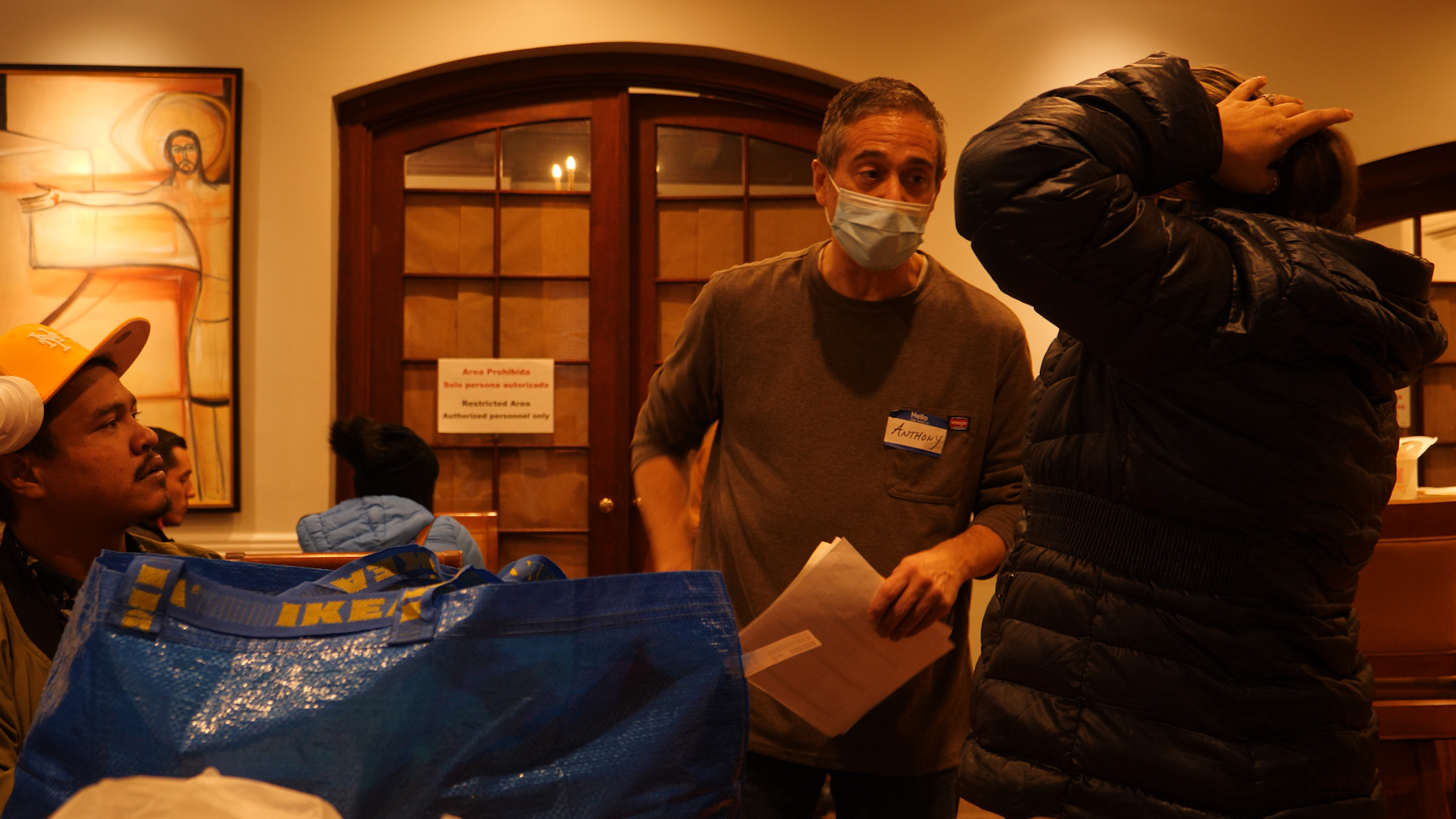

Anthony Pérez explaining forms to two immigrants. Photo by Samyu Sridhar.

Pérez, who has organized for Faith in New York and lobbied on behalf of DACA recipients, feels that it will be necessary in the coming months to “push City Hall hard.” Pérez said that the city government may be well-intentioned, but they just can’t afford to fill vacancies for certain initiatives due to a lack of funding. “In that kind of atmosphere, we know that to be able to provide services for this group of immigrants, we’re going to have to push politically.”

The preliminary 2023 budget for the Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs allots $50.8 million for “key immigrant services,” including IDNYC, ActionNYC, and the Adult Literacy initiative. This number is less than 1% of the city’s total budget and $21.6 million less than the adopted 2022 budget. ActionNYC, a legal services program, and Adult Literacy Initiative, an ESL education program, are both outsourced to a network of community-based organizations affiliated with MOIA, some of which are faith-based.

Though these governmental measures are in place, immigrants are still getting lost in the processes behind these measures. The months-long process of waiting for deportation cases to be heard in order to obtain a work permit leaves a large gap of unsupported time in which immigrants cannot work; many don’t even have access to adequate legal aid. According to the Vera Institute, 60% of non-detained immigrants with a legal defense win their cases as compared to a 17% success rate without a legal defense.

“You can’t press pause on a human being’s life,” said Kezadri.

St. Francis Church’s website says that the migrant center is “inspired by the Franciscan tradition of ministering to people who are alienated, displaced, or persecuted.” Led by Friar Julian Jagudilla and Pérez, the migrant center has taken up Mayor Adams’s call to action by hosting clothing and food donation centers three times a week.

During the clothing drives, Pérez calls asylum seekers waiting in the pews of the church into another room, where he and other volunteers assess their forms and pull from a treasure trove of donated clothes to match their requests. The storage rooms of the church are filled with racks of clothing, organized by gender, size, and age, as well as toiletries and essentials for infants, such as diapers. These items are mostly donated and funded by the members of the church.

Donated clothing storage room. Photo by Samyu Sridhar.

Pérez and Jagudilla have taken their efforts one step further by beginning to meet with migrants to better understand their needs. “At present, the assistance that we’re providing is just hope, and some material needs like food and clothing assistance,” said Pérez. “We are telling them that we are welcoming them, we are inviting them to community events here at St. Francis, and we are just getting some organizing off the ground.”

In those one-on-one meetings, Pérez hears peoples’ personal complaints and creates a plan to address them. Just last week, Pérez had a number of people alert him to the possibility of a hasty eviction from the Stewart Hotel, one of the sites that was chosen to house immigrants following the closing of Mayor Adams’s “tent city” due to upcoming cold weather. They may have to uproot their lives yet again to move to a less accessible area of New York.

“[The immigrants] were in a state of panic because they were being told that they needed to sign some kind of documentation, and be prepared to move at a moment’s notice,” said Pérez. The timeline of these complaints aligns with the announcement of the transition from the Stewart Hotel as an NYC Department of Social Services emergency shelter to a Humanitarian Emergency Response and Relief Center.

“Some of them were feeling intimidated and powerless, and just not knowing what their rights are, were signing it, thinking that they had no say in whether they could stay or they were to be moved,” Pérez added.

Similarly at Muslims Giving Back, Kezadri has been receiving immigrants who have had challenging experiences within the NYC shelter system. Shelters are overcrowded, dilapidated, and prone to violence, and they are not equipped to handle the rising influx of people. “A lot of people are coming back to complain and saying, ‘I don’t feel safe, I don’t feel comfortable, I don’t feel good,’” said Kezadri. “They’re unable to practice, they’re unable to do what they need to do to live.”

Kezadri has been with Muslims Giving Back, an organization that practices “faith in action,” for 10 years; she is now the director, and she oversees every step of the integration process for immigrants. Muslims Giving Back, in collaboration with the attached Muslim Community Center, shelters immigrants in their masjid, provides English classes, holds meal services, facilitates job and apartment placement, helps secure legal aid, and invites new immigrants to join prayer services.

Kezadri is deeply motivated by the core Islamic belief of serving one’s community. Community is an all-encompassing term in Islam; the Quran states that one should “show kindness to parents, and to kindred, and orphans, and the needy, and to the neighbor that is a kinsman and the neighbor that is a stranger, and the companion by your side, and the wayfarer, and those whom your right hand possess.”

“For me, in Islam, that’s the predominant definition, to be peaceful, to serve,” said Kezadri. “When we heard about the migrants coming in through Port Authority, we felt like, ok, what’s going on, what do they need, how can we serve them?”

Muslims Giving Back has a warehouse of food stock and a large, bare-bones space, but they are running almost entirely on donations from and fundraising by the masjid community. Currently at capacity, their resources are stretched very thin. “Unfortunately with what’s happening with COVID, post-pandemic, and now the financial crisis that’s happening, those community members that we’ve been relying on for so long are unable to provide,” said Kezadri.

Food storage room at Muslims Giving Back. Photo by Samyu Sridhar.

Muslims Giving Back has not yet received any funding from the city budget. Kezadri fears that there is an inequitable distribution of resources among different groups of immigrants, and that Muslim immigrants are not a priority. “It’s just politics, and if a certain group doesn’t fit into certain politics, then your priority just basically falls,” said Kezadri.

Charlie Davidson is trying to combat these inequities through advocacy. As the co-chair of Synagogue Coalition on the Refugee and Immigration Crisis, a volunteer-led organization, his goal is to educate the communities within the synagogue coalition to actively participate in political demonstrations and direct service for all immigrant and refugee communities. “Everything that everyone does everywhere is incredibly short-term and reactive, because there isn’t a bipartisan leadership that’s going to cause a rational immigration policy to emerge,” said Davidson.

Motivated by their religious beliefs and their historical experience of oppression, as is stated on their website, the SCRIC has run donation drives, raised funds for resettlement of refugees in New York, and sponsored workshops on the legal and administrative aspects of the immigration process, among other things.

St. Francis Church, Muslims Giving Back, and SCRIC all came to a consensus on what the administration needs to do at the very least: make clear what resources are available to immigrants and that they know their rights. “Before we can tap into those resources, we need to be informed of what those resources are,” said Kezadri.

The passion and determination organizations like St. Francis Church’s migrant center, Muslims Giving Back, and SCRIC are bringing to this humanitarian crisis has been a godsend for people who might have otherwise fallen through the gap.

Viviana Flores had been in the U.S. for 15 days after traveling from Colombia; she was staying in a hotel on 44th street in Manhattan, where her son was sick with a respiratory virus and her husband was injured. St. Francis Church was her first stop. “They have helped us a lot with finding doctors,” said Flores.

For Flores, attending mass was a family affair; she would gather her loved ones and go to church every Sunday. She continues to lean on her faith even as she arrived in the U.S., hoping to attend mass with her family again. “It’s very beautiful,” Flores said of faith and Catholicism. “My soul is strengthened by my faith, which in turn works to solve my problems.”

Three months ago, Mamadou Diallo left Senegal in search of better work in order to provide for his family. He now works in the Muslim Community Center, helping to organize and tidy the masjid and welcome people in for prayer. “Here, Alhamdulillah, [Muslim Community Center] received me. My family is here in MCC. It’s your house, your family. Muslim all is one family.”

Kezadri encourages the immigrants to eat together, pray together, and make friends with one another. She invites members of the masjid community to come socialize with and mentor the newcomers because she believes that community integration is vital to ensuring the immigrants’ long-term well-being and independence in this country. “This is their way to link themselves to their roots,” said Kezadri. “This is their way to feel a sense of rapport and connection.”

Women grouping together for Jummah prayer in the Muslim Community Center. Photo by Samyu Sridhar.

Compassion in Crisis

By Crispin Kerr-Dineen

“This is happening all over the country,” said Jmel Wilson, vice president of Neighbors for Refugees, when asked if private citizens have been willing to open their homes to recently arrived immigrants.

In contrast, Rownoka Ashakhan, a case manager at CIANA (Centre for Integration and Advancement of New Americans), like many in the city, when asked about private housing for recently arrived immigrants, acknowledged that the organization had not “personally heard about this.”

Yet many would agree that private housing for newly arrived immigrants is central to their welfare and assimilation.

Recently, immigrants have been arriving in the United States in such large numbers and with such a pressing need for accommodation that many are increasingly chaperoned from shelter to shelter and even from hotel to hotel.

This function is the only way to fulfil statuary obligations to provide housing in New York. Still, it has meant the vital process of assimilation for many people has ground to a halt. For it to begin, the urgent need is for housing and the crucial postal address it provides.

In short, immigrants need a place to call home.

The last few months have seen more than 24,000 migrants arrive in New York City alone, leaving the shelter system on the brink of collapse.

The current system for providing shelter to newly arrived immigrants traces its origins to the Refugee Act of 1980. According to the National Archives Foundation, the Act—which was a direct response to the Vietnamese and Cambodian refugees wanting to flee during and after the Vietnam War—was established to ‘raise the annual ceiling for refugees from 17,400 to 50,000.‘ This groundbreaking Act also allowed a constant process of “reviewing and adjusting the refugee ceiling to meet emergencies.”

“The Refugee Act of 1980, that’s a landmark,” remarked Kelly Agnew-Barajas, the director of Refugee Resettlement at Catholic Charities of the Archdiocese of New York.

It meant that refugee resettlement became “codified.” The Act led to state and federal agencies working closely with nine well-established organizations to manage the resettlement of refugees. In turn, this collaboration led to the instigation of sponsorship programs, which involved providing financial support for immigrants, formalized through the system of I-134 forms.

An I- 134 form is a Declaration of Financial Support that potential sponsorship families fill out and are crucial in finding private housing for immigrants.

And now, with the shelter system in crisis, the reliance on sponsor families filling out these forms has become more critical than ever,

“The public shelter system, I would say, is terrible, because you’re single, it’s very disruptive, it’s dangerous, stuff is stolen, it’s very stressful, there’s a lot of noise,” Agnew-Barajas acknowledged, “not only is it stressful for these people arriving, but it also costs the state a lot of money.”

“The cost is something in the range of $35,000 per person per year.”

Agnew-Barajas added that while “it’s important to have shelter in the short term, a crowded shelter is a challenging place to plan your next steps in a foreign country.” In her view, “the system is overrun, meaning responsibility filters down to smaller, more local organizations.”

Yet this filtering down of responsibility, on its own, is no magic solution.

“With the rising house prices, that’s not to say that these organizations find it any easier to help get people into private housing. We give immigrants guidance and support and case management, but in comparison to housing, that stuff is cheap,” Agnew-Barajas added. “Once they [the government] give us money for housing, it’s a bottomless pit. No one has the budget big enough to support people’s rent for a reasonable period of time.”

So now, with existing systems overrun, there’s a desperate call for voluntary organizations and even individuals to help.

It became clear that “the volume of people who needed refugee resettlement services was simply not possible for the nine agencies to attend to,” explained Wilson, the vice president at Neighbors for Refugees.

Neighbors for Refugees is an organization based in Westchester helping refugees and asylum seekers reach the point of self-sufficiency. It identifies the need to provide appropriate housing, supplemented by the support which can come from individual sponsorship and counselling. These are fundamental to its aim, suggesting that money is one of many resources in short supply.

“The work has been so intensive since the fall of Afghanistan that the agencies have had to insist their caseworkers do not take calls at night or weekends, but that’s when cases happen invariably, right?” Wilson added with a weak laugh.

By offering this sponsorship, organizations like Neighbors for Refugees and their volunteers are helping provide a bridge in the short term to allow people to get on the road to assimilation.

“It’s the personal commitment that changes the trajectory,” explained Wilson. Indeed, it is deeply personal: the organization “pays for 100% of living expenses until they’re employed.”

Agnew-Barajas endorses the value of this approach. “We’re dependent on them [sponsorship families] … they’re [Neighbors for Refugees] like the real deal sponsors, they sponsor right. They materially sponsor with financial commitments and planning. [It’s] really thoughtful work.”

Neighbors for Refugees does also rely on acts of kindness from the local community. There have been occasions when even the organization are struggling to find private housing for immigrants, and citizens have stepped up and said they would house immigrants until Neighbors for Refugees can find private accommodation.

Although admittedly, the work of Neighbors for Refugees is on a small scale, it is effective and very often successful in setting up families.

Elaine Wanderer, board member and secretary at Neighbors for Refugees, illustrates the point when asked on finding housing for immigrants: “I think we’ve been fortunate.”

Wanderer has been working with a newly arrived family of six from Sudan since March, leading a team of five core volunteers helping the family settle. These volunteers work with the family to help them understand everything from budgeting to their responsibilities.

This particular family moved from war-torn Sudan to a refugee camp in Jordan, where temperatures sometimes hit freezing at night.

In these refugee camps, their “needs were being met but not particularly well,” she said, “in comparison to where they are now with stable housing, I think that has made all the difference.”

Again, the message is repeated: stable housing is fundamental to successfully build a life in the U.S.

“First step is housing. Housing is important for all kinds of people in transition,” Wanderer said. “If you have a house, you can get mail; you have some stability, security, and a roof over your head to keep the rain off and the cold out. It’s really important.”

Once stable housing is acquired, the family can move on to think about other things, like English language classes, increasing their employability.

Now this family’s mother takes English classes four days a week, and the father goes on Saturdays, with classes also provided by Neighbors for Refugees in the evenings during the week.

The case workers and their connections have been fundamental to helping families find employment.

The family’s father will shortly be starting a job in a hospital—an opportunity which came about because of a team member’s connection with someone at the hospital.

Jobs bring stability, and very often, the work of Neighbors for Refugees finishes at that point.

As if the additional pressures created by recent upheavals in Venezuela and Afghanistan were not enough, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine earlier this year has forced the U.S. government into creating one of its most extensive sponsorship programs in recent history, Unite for Ukraine. As of September this year, over 123,000 applications have been received from families looking to help. With over 50,000 Ukrainians having already arrived, the program has been a success.

However, this isn’t to say that these various sponsorship programs don’t have their problems.

“There are some bad actors that have tried to traffic people. It’s not legally binding [the I-134],” Agnew-Barajas explained. “They lose nothing by submitting this application. They don’t have any obligation to do anything. We’ve seen a lot of what they’re calling sponsorship breakdown.”

But despite these problems, there can be no doubt that volunteers can make a difference.

“We’ve resettled dozens of families to which it’s meant a lot to them. But, we are aware of the millions we can’t help, because we can’t help everyone,” Wilson concluded.

Seeking Shelter for Asylum Seekers

By Mano Baghjajian

In June of 2022, Michael, whose name has been altered in order to protect his ongoing asylum case, was on a plane heading toward Mexico. He was fleeing the oppressive and authoritarian government of his home country of Iran.

His plan was to gain entry to the United States via the Mexican border and begin the asylum-seeking process.

“It was very hard to get into the United States,” said Michael. “Once I crossed the border they gave me an airplane ticket to New York. I didn’t have a choice on where to go so I just listened to them and came here.”

With everyone he had ever known being back home in Iran, Michael arrived in a new city in a foreign country completely alone.

Through word of mouth, Michael was able to find the We Are Not Afraid Community Resource Center, a nonprofit organization that runs a shelter in Harlem exclusively serving asylum seekers and refugees.

WANA was able to assign Michael an asylum case manager who has begun the process of getting him documented in the United States.

“When he came here he hit the pavement with everything squared away,” said Ryan Oveisi, 30, Michael’s asylum case manager. “With work, with his visa, with getting a lawyer, with housing. There is never a chance to rest.”

Michael is just one example of the crisis that New York City is currently grappling with, that of the recent influx of migrants to the city. These migrants are coming from all over the world, from asylum seekers trying to escape from cartel danger in Central America, to people from economically unstable nations like Venezuela, to people trying to escape war-torn Ukraine.

“The issue has always been a thing, there are just more people this time around,” said Ameya Biradavolu, 28, the executive director of WANA Community Resource Center. “The mayor made a ton of promises, making announcements saying everyone can come into this city, but they had nothing planned. It has led to lots of chaos and craziness.”

Around 20,000 migrants are believed to have entered the city in the last few months. While some are struggling with issues like jobs and language training, one huge factor that is affecting a huge portion of the migrant population is housing.

These migrants have made the journey to the United States in order to be granted legal asylum, which is a process that can take many years to complete. There is a negative connotation around the migrants, with those uneducated assuming that they are here illegally. That is far from the case.

“It is legal to come onto U.S. soil and plead your asylum case, but for a brief period of time they are undocumented,” said Biradavolu. “There are refugee reallocation funds that are supposed to be used to place people of all different designations in temporary housing. Refugees get status before they come into the country, asylees file after getting into the country.”

To combat the issue of housing among the migrant population, New York City had opened up relief centers around the five boroughs. These centers are large tent encampments that are providing food, medical care and a bed to sleep on along with other social services.

However, with the arrival of winter right around the corner, these outdoor tent encampments are now becoming unusable as a source of housing for the migrants. Some have begun shutting down, including the tent encampment on Randall’s Island, which had around 500 available beds. The migrants who were being housed here are being moved to hotels in Midtown.

“New York is a cold place, all these people came in the summer with no infrastructure for when winter comes,” said Biradavolu. “It was really bad planning on the city’s part.”

The city has also been renting out hotel rooms specifically for migrants. Places like the luxurious Row NYC hotel in Midtown have been housing around 200 migrant families. The hotel is being classified as the city’s second-largest migrant relief center due to the sheer amount of people that they have been taking in.

Representatives of the ROW NYC hotel declined to comment for this story.

The scramble and uncertainty on the city’s part regarding housing for the incoming migrants has been leading them to the shelters around New York. However, there are only so many beds available, with the demand overwhelming the system.

“We have been dealing with the same thing that we’ve always been dealing with, there are more people than we have spaces, people are coming here straight from flights, straight from detention centers,” said Biradavolu. “The city pledged to put funding into shelters, but the way that they were doing it didn’t make a lot of sense.”

The WANA shelter has been doing its part to house asylum seekers and move along. One of those people is Shazakye Mustafa, a social work intern from NYU Silver who herself also manages a number of asylum cases.

“I really wanted to be a part of actively helping to create a positive communal outcome,” said Mustafa, 25. “I think with this work that we do, we are seeing the systems that need to be changed, part of our work here is getting towards that.”

The shelter has been putting in the effort to connect the asylum seekers they serve with the proper services they would need to assimilate into American society, such as language classes and getting them in touch with lawyers who will represent their asylum cases. But the length of the asylum process makes it difficult to see a clear picture of it all.

“When people leave this shelter, many of their cases are still ongoing. That can feel like a barrier for people towards creating a plan to find housing and employment, said Mustafa.” “It’s been challenging with the uptick in migrants coming and trying to find them places to stay. There aren’t a lot of resources for asylum seekers.”

Due to their limited capacity, only eight beds, and a long waitlist, the WANA shelter only allows people to stay at their facilities for up to one year, after which they must leave to make room for new asylum seekers.

“After one year I must leave here, they only guarantee me living in this shelter for one year,” said Michael. “I haven’t been able to look for a more permanent place yet because I don’t have anything yet.’

Michael is in a waiting period for getting work permit authorization, which is dependent on him improving his English through an English language class as well as finding a course that will give him an electrician’s license.

Michael studied electrical power engineering back in Iran and hopes to use that skill to find him a well-paying job upon approval.

“There is no time to make friends or to do anything else,” said Michael. “There are many problems and I only have one year to fix them. All my time goes into getting me ready, there is big stress all the time.”

Michael has also struggled with finding proper translation services, with the current infrastructure leaning heavily toward Spanish speakers.

“The United States only has a plan for Spanish speakers. I have skills, if they gave me a good plan my situation could improve fast,” said Michael. “It is hard for people from other countries, Iranians have a big problem with their government right now so many people will need help.”

The WANA shelter is a great example of people coming together to help the recent influx of asylum seekers, but there is only some much time and resources available for nonprofits like WANA. For real change to occur, the local government needs to be more organized and efficient in handling this crisis.

“All these services that the city is providing requires Social Security numbers,” said Biradavolu. “If you’re focusing on a population that is still waiting for their documents, you need to have services that support them.”

Local shelters are above total capacity, with the number of people in these facilities passing 60,000. This is leading to more people on the streets, with many of those people just arriving here. With winter just around the corner, the people unlucky enough to be accommodated by one of these shelters will end up suffering.

“It is sad to say but a lot of people are going to end up on the streets because even the shelters are overwhelmed,” said Biradavolu. “It really has been regular people dealing with the crisis, the city has to do more and be honest about where we are at.”

The migrants are here to stay, so in order for them to become part of normal society and be given the ability and opportunity to live normal lives, those in power at the local level need to propose permanent and effective solutions to provide these people with the basics until their asylum cases are settled.

“What is lacking is an infrastructure to get them the services they need, whether it be health care, translation services, legal services, it doesn’t exist in New York City,” said Oveisi. “If there was a central place here in the city it would be so helpful for these people.”

The Journey of Mind

By Tenzin Zompa

The Rock Church in Queens is filled with Venezuelans on Sundays. They gather as a community to pray and enjoy each other’s company over lunch. It is one of the few churches in New York City that organizes every activity in Spanish; that is a major reason why a large number of new migrants from Venezuela prefer to visit the church.

It is their home in a foreign land.

The Rock Church. Photo by Tenzin Zompa.

Quietly sitting on a staircase inside the church by himself was Lewis Fernandez, a 30-year-old Venezuelan who migrated to New York without any family.

He was in the military back in Venezuela but here in New York, he works at a restaurant. Finding this job was difficult but people at the church helped him get hired.

Venezuelan Migrants at The Rock Church. Photo by Tenzin Zompa.

It has been emotionally and mentally hard for him to leave his hometown. He described the difficulty as “12 on 10.”

“I had to leave everything and everyone back home.”

With the recent influx of migrants coming into New York city, the government and the nonprofit organizations are coming together to help them with food and shelter. However, providing necessary attention for their mental health has not been a priority, according to advocates.

Rachel Lee is a psychologist who has been working with migrants since 2008.

She says that depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder are the four common mental health issues that migrants deal with.

“In psychology we call it ‘migratory grief’—leaving behind family and friends and for many people also their career.”

“There are people who are accomplished, there are doctors who can’t practice in this country, people who have to take jobs that are not in the area that they were in their home country.”

The government of New York provides mental health counseling for migrants and other basic health care facilities but migrants need to check their eligibility before getting access to these facilities.

Lee believes that there is a “lack of availability in terms of both affordable care” and trained workers who are experienced in dealing with asylum seekers. Such trained workers are crucial to better understand the psyche of these people who are “forced into migration.”

Lee has been volunteering as a psychologist at Venezuelans and Immigrants Aid, a nonprofit, since 2018. One of the activities VIA initiated is a peer support group. Two therapists and other volunteers at VIA communicate with migrants to listen to their concerns and find possible solutions to tackle them. It is Rachel and VIA’s attempt to “re-establish a sense of community that gets lost with leaving your country.”

She says such activities are important so that “not everybody has to start from zero.”

Discussing mental health openly and seeking therapy are still not common in Venezuela, especially among men. Therefore, for Lee, she had a greater number of women seeking help and taking advantage of free therapy than men.

Migrants never want to leave their country, but they flee unwillingly, largely due to economic and political unrest in their country. So there is a sense of loss and longingness when they pack their whole lives in a bag and head to another country.

For Fernandez, the United States is the country where he can still dream big.

“Everything is possible in this country. You can be here today and move to another state tomorrow,” he said. He wants to bring all his family here for a better life.

According to the American Psychiatric Association, post-migration stressors such as prolonged detention, insecure immigration status, and limitations on work and education, can worsen mental health. Despite the tremendous pressure to build a new life, these Venezuelan asylum seekers feel extremely optimistic. Perhaps, it is their strong faith and refuge in God. “Whenever I feel stressed and lonely, I look for that light that keeps me motivated. By the grace of God, I am strong enough,” Fernandez said.

He believes he can figure out everything else as long as he is healthy and has a job. He feels at home in the Rock Church, surrounded by his people, who speaks his language. Visiting the church makes him feel less lonely.

Alex, who declined to give his full name, is a testament to that. He arrived in New York with his wife and two children last year in December. They currently live in a shelter. He had an accident (a car hit the taxi he was in) and hurt his back and he lost his job. He can only work part-time right now, but he said his belief in God keeps him going.

Alex doesn’t have a Social Security number to apply for a stable job and shoulders the responsibility of his family, but he says changing his mindset to think positively helps him deal with hardships. “‘This is just a phase that will pass away.’ I repeat this to myself, and it helps.’”

Most of these Venezuelan migrants cover the distance on foot with hopes to earn money for themselves and for their families back home in Venezuela. But many of them are unaware of the struggles that lie ahead.

Niurka Melendez is the co-founder of VIA. She and her husband came to the U.S. with their son in 2015 and started the nonprofit in 2016. Ever since, they have been restlessly working to provide information, legal aid, professional psychological therapy, online English classes, clothing donations, and many more for the Venezuelan migrants coming into New York City.

Niurka Melendez, Co-founder of VIA. Photo by Tenzin Zompa.

“A lot of them are innocent in the sense that they are unaware of the long battle of seeking asylum that lies ahead of them,” said Melendez.

She said a lot of migrants from Venezuela pay guides to bring them into the U.S., but most of these “guides” are traffickers. They deceive these migrants into thinking that they would be granted asylum the moment they enter the US border.

These new migrants are still digesting the fact that they are here and alive,” Melendez said. “And then to realize all the things they still have to go through are frustrating for them.”

Yubisay Rivero Pacheco, migrant from Ecuador. Photo by Tenzin Zompa.

It has been mentally exhausting since the day she left her hometown.

As her voice cracked and tears ran down her cheeks, she explained how terrified and hopeless she felt. “There are days when I feel like running away.” When asked what keeps her going despite all these struggles, she said: “my children and God.”

When the struggle feels endless, Pacheco said that “sometimes I cry and sometimes I go on walks.” She also seeks professional help from a therapist that is facilitated by the shelter that took her in.

She says the shelter has all the facilities they need but is surrounded by sex workers and drug addicts. She hopes to find a job so that she and her children can move from there and lead a “normal life.”

Melendez is still waiting to get her asylum papers approved. “I am disappointed in the system, but I cannot sit back and do nothing. I have to get up and help all these new migrants help with whatever I can.”