From Cross-Country Borders to Language School

A Story of the New Immigrant in New York City

By Seyeon Bang

People cross the borders of the United States every day in pursuit of a dream. Some come to America for higher education, some for political freedom, and many others to escape war and conflict in their home countries. Many immigrants arrive in New York City in anticipation of living in a city of dreams. However, what awaits them is yet another obstacle: the language barrier.

Without the ability to speak English, finding a job, getting an education, or even making friends is incredibly challenging. To overcome this hurdle, many immigrants search for English learning centers.

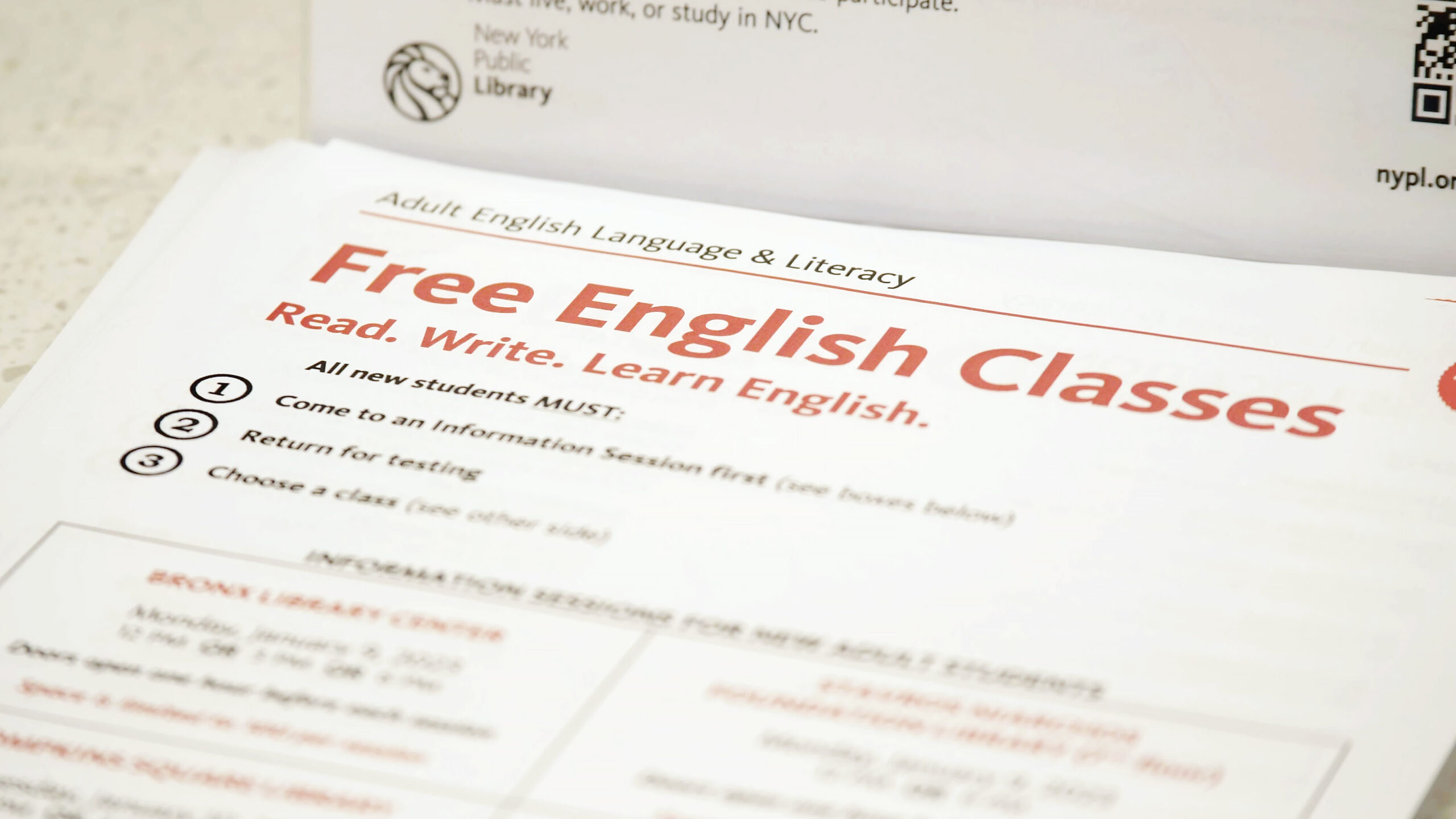

New York City provides free English Language Learning programs to immigrants through a walk-in system at 11 public libraries across the five boroughs. Among them, Stavros Niarchos Foundation Library (SNFL) in Manhattan offers the largest number of classes, so its 6th floor is often filled with students who have come to improve their English skills.

One class at maximum capacity is Intermediate Conversation, which is mostly filled with students who have been in the U.S. for less than half a year.

Chinese and Spanish speakers often learn English by helping each other whenever unfamiliar words come up. Outside of these communal peer dynamics, Mariam Gurgenidze, 21, the only student from Georgia, struggles to keep up with the class, in which her only outside source of help is Google Translate.

A desk with Mariam’s name card.

Gurgenidze began taking the classes after her younger brother found out about them on social media.

“I come here three days a week and it’s great because it helps me overcome the language barrier and communicate with people,” Gurgenidze said.

Gurgenidze arrived in the United States in April. Her father and brother already live in New York City and she says she plans on studying education in college because completing the same major in Georgia pays less.

“When I first got here,” Gurgenidze continued, “it wasn’t too hard to settle down because I had family here. Also, because many people are in a similar situation as me, we often practice together and this helps us overcome difficulties in communication.”

The NYC Department of Youth & Community Development (DYCD) also allows immigrants to apply to education programs run by nonprofit organizations for speakers of other languages. People can search for them in their native tongue by borough, neighborhood, or zip code, and discoverDYCD provides contact information, activities offered, and a mapping feature with navigation.

A total of 87 programs are offered throughout the five boroughs, with 20 centers located in Manhattan. Beyond their reduced class sizes and spoken language practice, nonprofit language centers offer more classes with an organized syllabus on grammar and writing courses, compared to the on-request participation in the public library system.

Among them, the COPE Institute, the non-profit education branch of Agudath Israel of America, also assists immigrant students, especially those who have recently fled from the war. The classes are taught by teachers who also immigrated to the U.S. some time ago, so many of them are more empathetic towards the students.

Zoriana Murashka, 25, from Ukraine has been in the U.S. for two months and at the institute for two weeks. She says her teacher helps her not only to learn English but also integrate into the American way of life.

Zoriana Murashka taking an English class at COPE Institute.

“It’s exciting to learn about everything. I was happy that I was here when Americans celebrated Halloween and Thanksgiving Day,” laughed Murashka.

Having spent six years working as a journalist and magazine editor in Ukraine, she wishes to continue her career as a journalist after getting a firm grasp on English.

“I should decide whether I go into journalism or not. However, I need to become fluent in English first. Without English, it’s almost impossible to get a job here,” she added.

Under the Uniting for Ukraine program, Murashka holds a two-year permission visa. She is unsure what the U.S. government will decide after two years. Over the next two years, she plans to learn English and contribute to the recovery and renovation of Ukraine. She stressed that her country should not be remembered only for its tragic history.

“I have a lot of information about my country to share. It is my hope that my English skills will help me to convey the culture, tradition, and people of my country to audiences,” said Murashka.

Absalon Zuniga, 59, who immigrated to the U.S. from Ecuador 12 years ago, attends English classes twice a week at the COPE Institute. He recalled that he had to drive a truck from dawn to dusk every day when he arrived here in New York City.

Zuniga now works part-time at a food company and spends eight hours a day at JFK Airport three days a week. He said he finally has some free time, so this is his first time learning English in a classroom setting.

“The most important thing for me is to communicate well with my customers,” said Zuniga. “Also, I want to own a truck and work on my own after I retire in three years.”

Similar to Gurgenidze, Murashka, and Zuniga, most immigrants in New York City often begin their journey by searching for English centers. However, despite support from the government, the number of free English classes is not enough to meet the high demand.

There are only two English teachers at Stavros Niarchos Foundation Library (SNFL), and one of them has more than 25 students in one class. Since students are allowed to participate on-site without prior registration at the public library, there is a constant influx of students and extra chairs often have to be brought in to accommodate them. Some courses offered by nonprofit organizations even have a waitlist for classes.

Raizel Rusanov, the program director of COPE Institute, said the recent influx of immigrant students this year can be attributed in part to the Russia-Ukraine War, as well as borders reopening after the pandemic.

According to The New York Times, more than 22,000 immigrants have arrived in New York City since April.

“Last year, there was a lot of immigration that was at a standstill because the consulates were closed for the pandemic. So people could not physically come here,” Rusanov said. “Now consulates and embassies in other countries are giving visas again so immigrants come to the U.S.”

Flyers advertising free English classes at Stavros Niarchos Foundation Library (SNFL)

To make things a bit more complicated for such students, public libraries in New York City only provide foreign language flyers based on the population in their neighborhoods. Immigrants who live in too small a community will not be provided with flyers in their native language, leaving them out of the loop regarding important information for English classes. Although library branches can request flyers in a foreign language, this is unlikely to occur until a particular language group attends in large numbers.

Nevertheless, immigrants give and receive help in the community they belong to.

“Students find our institute through their friends. Some people are following other ethnic social groups on WhatsApp, on Telegram. They spread the word within their own ethnic group,” said Rusanov.

For many new immigrants in New York City, crossing the border is one major obstacle, but there are countless others they must overcome to settle into their new home.

“At this moment, I should find myself, find my way in the new country,” said Murashka. “But I put all my efforts toward studying English because it will be easier to find something.”

Some of the interviewees’ answers were translated from their native language to English.

Language for All

By Ke Chen

Around 2:30 on a sunny afternoon last week, the children’s laughter filled 183 South 3rd Street as the bell rang, bringing everything around the building to life. Anelin Flete, Community School Director from MS 50 El Puente Community School, was surrounded by a group of newly arrived students, seeing them off in front of the school gate.

Anelin Flete, chatting with migrant students about their school life. Photo by Ke Chen.

More than 27,000 Venezuelan asylum seekers have been sent to New York City since the spring, the majority of them coming with nothing. Fortunately, many communities in the different boroughs of New York City speak Spanish, which provides these newcomers with a sense of familiarity and helps them adjust quickly to their new life in the city.

The waiting line in front of the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Photo by Ke Chen.

“When they [migrant students] know people who speak their language or people from their places after they just got here, they feel safe. And that is a mission of El Puente,” said Bernardo Rodríguez, speaking through a translator, Efren Olson-Sanchez. They are both members from El Puente and now work as academic tutors at MS 50 El Puente Community School in Brooklyn.

Until now, MS 50 El Puente Community School has taken in 16 asylum seeker students aged 10 to 14. The school is responding proactively to help these children and the 16 families behind them before winter comes, providing clothing, legal resources, and educational information.

But even though Spanish is the most spoken language in New York besides English, the difficulties caused by not being able to master English have arisen over time for migrants of all ages.

Flete mentioned that one of her newly arrived migrant students, Dana, reached the age to apply to a high school, but she does not have the opportunity because the Specialized High Schools Admissions Test is in English, which she does not know.

To solve the language barrier, MS 50 El Puente Community School started to offer a Spanish dual language program in every grade level. It differs from a bilingual special education program it has, which teaches English and separates the students according to their needs. The dual language class is a regular class but is either taught in English or Spanish, allowing these new students to interact with the local students, and all of them will master two languages.

“They have to learn English; they live here,” Olson-Sanchez added. He teaches art in Spanish and partners with another tutor to transfer words into English so migrant students can build up their vocabulary.

However, an issue arises in dual language classes. “The biggest need and those kids are saying it themselves, is that they feel weird. Because right now, they’re sitting together in the classroom, all the other kids sit together, and the two groups seem separated. So they still feel the isolation. They’re complaining about it. We don’t want that too,” said Flete.

“So the principal and I are currently working together to figure out how we can utilize our funding to bring tutors, specifically bilingual tutors, into classes,” Flete added, “These tutors can help migrant students understand the material and immerse into the culture and talk to the other kids. But that’s expensive.”

Project Open Arms, announced by the city government this year, provides financial assistance for schools that accept migrant students. The school will receive $2,000 per newly enrolled migrant student. MS 50 El Puente Community School recently received $28,000 from project Open Arms and an additional $30,000 from Dream Team. But more funding for supporting immigrant students is needed.

Although MS 50 El Puente Community School is under financial pressure, the migrant students feel very safe within the new community. They come to school every day, and their English skills will be improved during their studies. But for those over school age, their language barrier means an inability to access crucial information, which can be inconvenient in different ways. Using a mobile translation app that requires the internet cannot solve the problem.

Before Jorman Vasquez, 22, came to New York City this summer, he didn’t speak a word of English other than his name. After four months in the city, he can introduce himself in English briefly.

Jorman Vasquez shared his experience of learning English. Photo by Ke Chen.

“I feel funny when I can’t talk to people who don’t speak Spanish here. I have to take out my phone and communicate through the translator. But I’m learning now,” said Vasquez. Now he stays in a church and takes classes offered by the Church and his Mexican friend.

In addition to everyday communication, using English can significantly help migrants find jobs.

“Even if I already have working permission, I would still want to learn English because it would be beneficial for my work,” said Anthony Guzman, 26, a roommate of Vasquez, “I could be a receptionist if I speak English.”

Anthony Guzman talked about his concern about language issues. Photo by Ke Chen.

In response to this challenge, the city offers different solutions. Churches, nonprofit organizations, public libraries, and government-managed programs across five boroughs have created spots to meet the demand.

One busy Monday morning last month, Venezuelans and Immigrants Aid (VIA) partnered with St. Paul and St. Andrew United Methodist Church, delivering free clothes and immigration-related information to a steady stream of refugees waiting in the hall. In one of the flyers provided by VIA, there is information about how to apply for free English classes.

VIA helped migrants on a Monday morning in November. Photo by Ke Chen.

VIA divides its free English classes into three batches: the advanced level for the VIA volunteers, the intermediate level, and one for kids and older people to help newly arrived community members increase the likelihood of better opportunities in the United States.

Hector Arguimzones, one of the co-founders of VIA, pointed out that if migrants “don’t learn English, probably in a city like New York City that has a large Spanish community, they won’t have problems, but they will find obstacles to work in terms of finding opportunities outside the Spanish community.”

When Arguimzones first came to New York City with his family seven years ago, he practiced his English in free classes offered by a public library. Today he helps more refugees from Venezuela through English.

Arguimzones pointed at the doors of the Church Hall, “I was talking to a guy [a migrant] this morning. If you speak only one language, Chinese or French, you will probably have only one door open, but English can open all these doors.”

One of VIA’s Saturday online English classes is with ESL (English as a second language) teacher Tilla Alexander for Venezuelans with intermediate to basic language skills. Each session consists of 10 classes held each Saturday from 11 a.m. to 1 p.m. Participants will receive a certificate of attendance after participating in all classes.

“We usually limit the number of students in a class to six or eight to ensure that the teacher can take care of every student,” said Arguimzones.

VIA does not just offer English language courses; it provides a full range of assistance to Venezuelan refugees. To apply for the course, they need to fill out a Google form in Spanish, which includes, in addition to some basic information, the following: Are you seeking asylum? Are you looking for work? What is the level of study in Venezuela, and what are the most significant challenges you encounter as a migrant in the United States?

Unlike NGOs such as VIA, which helps refugees through many aspects, the Riverside Language Program provides free full-time English classes, especially for newly arrived immigrants, refugees, and asylum seekers in New York City, with a class size of about 20 students.

However, Riverside’s English classes have more stringent application requirements and a more developed and intense curriculum.

For example, applicants must meet five conditions to apply. They must be over 18 years old, live in New York, apply for permanent residency or asylum, and be refugees, asylum seekers, or green card holders for less than three years. They must be able to attend the program in person full-time, Monday through Friday, 9 a.m. to 3 p.m., for six weeks. There is also a preschool test and a final test.

Notably, Riverside’s programs are designed to be very hands-on. For example, the curriculum includes civic education, IT mentoring, and job readiness workshops that refer community partners to potential job placements.

Although 1.87 million residents speak Spanish in the city, Vasquez still thinks it is essential to learn English. “English is a universal language. If you’re from China and don’t speak Spanish, and I’m from Venezuela and don’t speak Chinese, then we can communicate in English.”

In the face of the influx of Venezuelan refugees, many immigrants are making efforts to create a diverse and welcoming environment for newcomers through English. With this help, migrants are ready to start their new chapter of life.

Efren Olson-Sanchez said the enthusiasm among new refugees is palpable.

“When the [migrant] kids came here for the first time, they wanna see it all. They are super open. They want to fit in. They wanna eat the whole city in one bite,” said Olson-Sanchez.

Filling the Gap, Language Access for New Arrivals

By Christopher Cornejo

Migrant waiting to receive aid outside St. Paul & St. Andrew. Photo by Christopher Cornejo.

It’s a cold December morning in New York City. St. Paul & St. Andrew Church has its doors open; crates of fruits, vegetables and other food sit on the sidewalk nearby. A group of individuals are inside waiting to receive some of these items.

Sitting in the pews, talking in hushed tones, they are not unlike the congregations this church is accustomed to hosting. They’re happy to avoid the morning chill and even happier to fill their stomachs, two things that are easier said than done for them. That is because they are part of the more than 17,000 refugees and migrants that have arrived in New York City over the past year.

In October, Mayor Eric Adams issued a state of emergency declaration to steer all city agencies to support newly arrived migrants and asylum seekers. This has all unfolded following the political stunt played by Texas Governor Greg Abbot. Starting in September, Abbot, in an attempt to stir up anger and increase southern border security, has sent thousands of migrants in charter busses from southern states to northern, mostly blue states.

“We expect to spend at least $1 billion by the end of the fiscal year on this crisis,” Adams said in his state of emergency address.

Since then, while the influx of migrants has slowed, those that remain find themselves in a perpetual state of waiting. Waiting for work permits. Waiting in shelter lines. Waiting for a chance to live normally again.

This desire for normalcy is shared with organizations that are focused on servicing asylum seekers and migrants alike. From legal services for those seeking documentation to food and shelter centers. Translation and interpreter organizations in particular have felt the increasingly crushing weight that comes with the arrival of tens of thousands of people.

The language gap that is present for these newly arrived migrants and asylum seekers serves as an additional barrier to the plethora that exists for them already. Not all these migrants have this issue however, having learned the language previously, a rare occurrence for the groups that have arrived in the city.

“The language barrier, for me, it has not been that bad,” says Jessica H. a recent arrival from Caracas, Venezuela. She is one of the many hundreds of migrants that arrive weekly at St. Paul & St. Andrew Church looking for aid, but she is also one of the few that arrive familiar with the language.

“But that is because I learned English in Venezuela, I cannot say the same for everyone else,” she says.

Many of the migrants, Jessica says, struggle with learning the language, particularly when it comes to filling out or executing necessary legal documents. These documents are crucial components of the legalization process, something almost every single migrant that has arrived in this city must endure.

Because she already knows English, it is one less problem for her to worry about, a silver lining in a sea of desperation and hardship. She has been in the country for a month and a half and has been focused on a single objective.

“My main focus is to sort out my legal status,” she says. “That is what everyone wants the most.”

Associate Pastor Lea Matthews, who co-ordinates the distribution of food and resources at the church, says the documentation process, even for a native English speaker, can be extremely arduous.

“Even if you are a native speaker, it’s incredibly hard to make your way through city bureaucracy that is intentionally full of obstacles,” Matthews says. “Spanish translation and accompaniment are absolutely essential.”

New arrivals to the city must sort through the seemingly endless layers of bureaucracy and administration that make up the legal system they must become accustomed to. Having dealt with ICE and homeland security administration personally, Matthews feels even she would need someone to help guide her through the experience.

That does not apply to simply filling out forms, or ensuring appointment dates are set, but “also what this process is going to ask of me and how long it will be,” she says. “Those things are the greater pieces of information and that’s what we also help to provide.”

Matthews feels she is only doing what a higher power would expect of her, a common theme among similar organizations providing similar aid and resources.

“What we are all called to do as people of faith is respond to needs” she says. “It would be fabulous if governments…all coordinated to respond to human need with efficiency and care, when that’s not the case we step into the gap.”

St. Paul & St. Andrew Church is not the only organization attempting to fill the gap created by such a large influx of migrants.

Organizations like Respond Crisis Translation, which started in 2019, are doing all they can from completely overworking their largely unpaid staff. This organization specializes in translation and interpreter services for asylum seekers or third-party groups providing aid as well.

In 2021, the NYC Department of City planning reported that nearly a quarter of New Yorkers, close to 2 million people, are not English proficient. This number has only grown with the influx of tens of thousands of newly arrived migrants and asylum seekers.

Meg Sears, operations, and outreach lead for RCT is responsible for hiring and onboarding the interpreters at Respond. Most of the translators doing work for the organization are unpaid.

A bulk of the work is completed by more than 2,000 volunteer interpreters all over the world. All these volunteers are a small piece of a large network that she says is in desperate need of more funding.

Much of the blame falls on the ever-delicate geo-political landscape of the world. RCT attributes spikes in caseloads to global crises that erupt across the globe. These crises can be when a particular group or country finds its citizens displaced, like Afghans fleeing oppression from the Taliban, or Ukrainians escaping their war-torn homes.

“We see thousands more cases in that language, and we cannot just absorb it all as volunteers,” she says.

Sears is candid with what she feels is needed to help alleviate the overworked system she manages.

“Ultimately, what we do need is urgent funding to be able to pay project managers to lead those language teams, ensure quality control of translators, and just get translators proofread and assigned and sent back to the organizations.”

She points out the irony of the interpreter industry. It is one, she has noticed, that is filled with organizations that directly serve asylum seekers and refugees, yet do not have budgets set aside for language access services.

Romina Galloso also works at Respond, separate from Meg. She works in a more direct capacity with asylum seekers as a translator, as well as a trainer for other aspiring interpreters.

A native of Mexico, she is on the front lines of the humanitarian crisis, listening to migrants and asylum seekers as they share their experiences, and at times their trauma. She addressed the structural problems found within the interpreter service system.

“The city government, although they ask for all the paperwork, records and interviews to be in English, does not provide any language access tools like translators or interpreters, unless it’s a court hearing,” she says.

From her personal experiences with the U.S. and city government systems, Galloso does not feel these bureaucratic bodies are well-equipped to handle the increasing number of cases within the system.

“One of the biggest challenges that I’ve seen with having court interpreters assigned by the government, is they are not qualified to do this work,” she says. “Not only are they not qualified in the linguistic aspect, but they are also not qualified to handle the emotional side of it.”

The traumas experienced during a migrant’s travels can sometimes be absorbed by those helping to interpret. This can lead to miscommunication and a reduced lack of trust between migrants or asylum seekers and organizations or individuals hoping to aid them.

“You can’t just leave people to help others,” Galloso says. “You never know when it’s going to hit you, you never know when you’re going to get triggered.”

Trauma training is another layer onto of the already mountainous issue of language accessibility and interpreter services. Understanding how to interpret and translate is only half the battle. The situation is only exasperated by the introduction of legalities and technical necessities for one’s immigration status.

Iman Fawzy, executive director at the ANSOB center for refugees, located in Astoria, Queens, also works personally with refugees and asylum seekers who arrive to the city. She is an immigration specialist and DOJ-accredited representative, meaning she is qualified to provide legal advice and assistance to those in need.

She also identifies the language barrier and lack of resources to help lower the barrier as one of the primary issues plaguing newly arrived migrants and asylum seekers.

“It is a big obstacle for them, accessing several services they’re entitled to,” she said. “It can be a hurdle for people to help their children in school, or if they’re going to the doctor or they want to apply for citizenship for example.”

Thousands of migrants are missing out on these basic yet crucial public and social works due to their immigration status. This problem becomes a deeper issue with the introduction of a language gap.

This problem is begging for a solution, and various individuals and groups are working to provide it. From bodies like St. Paul & St. Andrew Church to organizations such as Respond Crisis Translation or ANSOB, migrants and asylum seekers have a few more opportunities to relocate and establish a new life in the country.