The Journey of Mind

By Tenzin Zompa

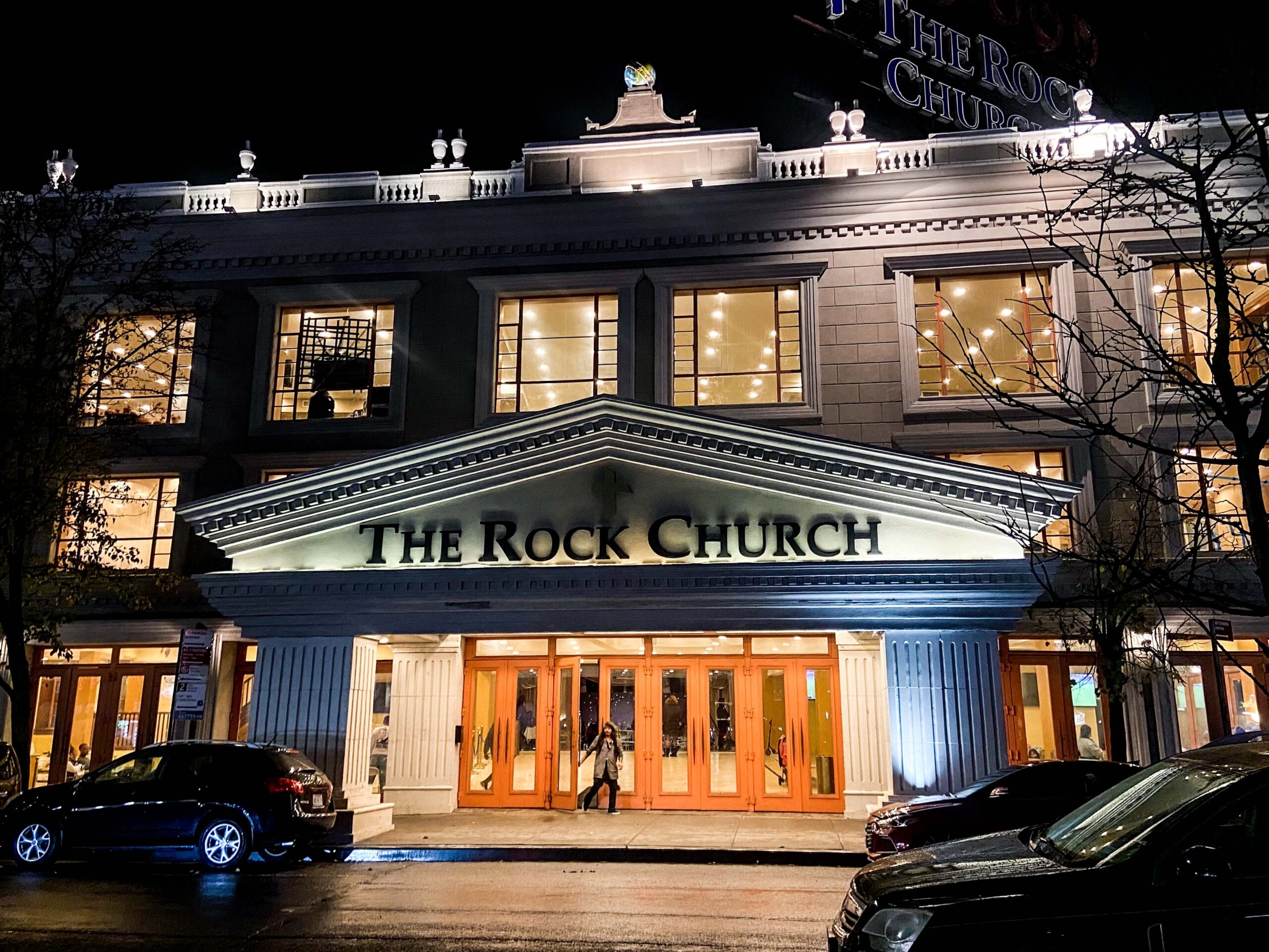

The Rock Church in Queens is filled with Venezuelans on Sundays. They gather as a community to pray and enjoy each other’s company over lunch. It is one of the few churches in New York City that organizes every activity in Spanish; that is a major reason why a large number of new migrants from Venezuela prefer to visit the church.

It is their home in a foreign land.

The Rock Church. Photo by Tenzin Zompa.

Quietly sitting on a staircase inside the church by himself was Lewis Fernandez, a 30-year-old Venezuelan who migrated to New York without any family.

He was in the military back in Venezuela but here in New York, he works at a restaurant. Finding this job was difficult but people at the church helped him get hired.

Venezuelan Migrants at The Rock Church. Photo by Tenzin Zompa.

It has been emotionally and mentally hard for him to leave his hometown. He described the difficulty as “12 on 10.”

“I had to leave everything and everyone back home.”

With the recent influx of migrants coming into New York city, the government and the nonprofit organizations are coming together to help them with food and shelter. However, providing necessary attention for their mental health has not been a priority, according to advocates.

Rachel Lee is a psychologist who has been working with migrants since 2008.

She says that depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder are the four common mental health issues that migrants deal with.

“In psychology we call it ‘migratory grief’—leaving behind family and friends and for many people also their career.”

“There are people who are accomplished, there are doctors who can’t practice in this country, people who have to take jobs that are not in the area that they were in their home country.”

The government of New York provides mental health counseling for migrants and other basic health care facilities but migrants need to check their eligibility before getting access to these facilities.

Lee believes that there is a “lack of availability in terms of both affordable care” and trained workers who are experienced in dealing with asylum seekers. Such trained workers are crucial to better understand the psyche of these people who are “forced into migration.”

Lee has been volunteering as a psychologist at Venezuelans and Immigrants Aid, a nonprofit, since 2018. One of the activities VIA initiated is a peer support group. Two therapists and other volunteers at VIA communicate with migrants to listen to their concerns and find possible solutions to tackle them. It is Rachel and VIA’s attempt to “re-establish a sense of community that gets lost with leaving your country.”

She says such activities are important so that “not everybody has to start from zero.”

Discussing mental health openly and seeking therapy are still not common in Venezuela, especially among men. Therefore, for Lee, she had a greater number of women seeking help and taking advantage of free therapy than men.

Migrants never want to leave their country, but they flee unwillingly, largely due to economic and political unrest in their country. So there is a sense of loss and longingness when they pack their whole lives in a bag and head to another country.

For Fernandez, the United States is the country where he can still dream big.

“Everything is possible in this country. You can be here today and move to another state tomorrow,” he said. He wants to bring all his family here for a better life.

According to the American Psychiatric Association, post-migration stressors such as prolonged detention, insecure immigration status, and limitations on work and education, can worsen mental health. Despite the tremendous pressure to build a new life, these Venezuelan asylum seekers feel extremely optimistic. Perhaps, it is their strong faith and refuge in God. “Whenever I feel stressed and lonely, I look for that light that keeps me motivated. By the grace of God, I am strong enough,” Fernandez said.

He believes he can figure out everything else as long as he is healthy and has a job. He feels at home in the Rock Church, surrounded by his people, who speaks his language. Visiting the church makes him feel less lonely.

Alex, who declined to give his full name, is a testament to that. He arrived in New York with his wife and two children last year in December. They currently live in a shelter. He had an accident (a car hit the taxi he was in) and hurt his back and he lost his job. He can only work part-time right now, but he said his belief in God keeps him going.

Alex doesn’t have a Social Security number to apply for a stable job and shoulders the responsibility of his family, but he says changing his mindset to think positively helps him deal with hardships. “‘This is just a phase that will pass away.’ I repeat this to myself, and it helps.’”

Most of these Venezuelan migrants cover the distance on foot with hopes to earn money for themselves and for their families back home in Venezuela. But many of them are unaware of the struggles that lie ahead.

Niurka Melendez is the co-founder of VIA. She and her husband came to the U.S. with their son in 2015 and started the nonprofit in 2016. Ever since, they have been restlessly working to provide information, legal aid, professional psychological therapy, online English classes, clothing donations, and many more for the Venezuelan migrants coming into New York City.

Niurka Melendez, Co-founder of VIA. Photo by Tenzin Zompa.

“A lot of them are innocent in the sense that they are unaware of the long battle of seeking asylum that lies ahead of them,” said Melendez.

She said a lot of migrants from Venezuela pay guides to bring them into the U.S., but most of these “guides” are traffickers. They deceive these migrants into thinking that they would be granted asylum the moment they enter the US border.

These new migrants are still digesting the fact that they are here and alive,” Melendez said. “And then to realize all the things they still have to go through are frustrating for them.”

Yubisay Rivero Pacheco, migrant from Ecuador. Photo by Tenzin Zompa.

It has been mentally exhausting since the day she left her hometown.

As her voice cracked and tears ran down her cheeks, she explained how terrified and hopeless she felt. “There are days when I feel like running away.” When asked what keeps her going despite all these struggles, she said: “my children and God.”

When the struggle feels endless, Pacheco said that “sometimes I cry and sometimes I go on walks.” She also seeks professional help from a therapist that is facilitated by the shelter that took her in.

She says the shelter has all the facilities they need but is surrounded by sex workers and drug addicts. She hopes to find a job so that she and her children can move from there and lead a “normal life.”

Melendez is still waiting to get her asylum papers approved. “I am disappointed in the system, but I cannot sit back and do nothing. I have to get up and help all these new migrants help with whatever I can.”