Zebra Mussels: A Hudson River Crisis

By Prabhat Seelamsetti

The Hudson River is one of North America’s most iconic and well known waterways. Roughly 30 years ago, it was also one of the most ecologically diverse aquatic ecosystems on the continent.

Since then, the river has dealt with a large number of sanitary and ecological issues, including pollution and salinity. One ecological challenge, in particular, has gone under the radar for decades: the rise of the zebra mussel.

Steven Pearson, the head of aquatic invasive species at the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC), has studied the mussels for years and spoke to how their minuscule size masked a major environmental threat.

”They’re very small, not very many people even know that they exist,” Pearson said. “However, those who live in, recreate near, or manage submerged infrastructure in areas where zebra mussels are, they know about this problem and they’re very concerned.”

Originally native to the Eurasian region, zebra mussels have been classified as an invasive species to the North American region.

They were first introduced to the continent in 1981 by attaching to vessels from their native regions and dispersing upon arriving in the new water bodies. This has been pinpointed as their primary means of invading foreign environments.

They did not make an appearance in the Hudson River until 1991, but upon being introduced they quickly multiplied and wreaked immediate havoc on the environment.

While the organisms are seemingly harmless, spanning less than 5 cm in size, they can reproduce at unbelievably quick rates and have drastic environmental effects in a foreign ecosystem.

“Zebra mussels cannot be eradicated from a landscape,” said Pearson. “In small, isolated water bodies an infestation could be eradicated, but usually once they’re introduced to water bodies they become a part of the invertebrate community and vastly alter the ecology of the system. Essentially on a broad landscape, nothing can really be done once they’re introduced.”

In one year, a single mature female can produce more than two million eggs while a single male can release an estimated two hundred million sperm. This allows for mussel colonies to form and span across a riverbed very quickly and eventually number within the billions across the entire system.

Once colonies are established a number of issues can arise. The waste that mussels produce is toxic to freshwater environments and limits oxygen levels while altering the surrounding water’s pH concentration.

The Hudson’s native “pearly mussels,” which once numbered more than one billion, only filtered the river every 2-3 months. This minimal level of filtering created the ideal conditions for the native fish, plankton and bacteria populations to thrive. After 1991, their numbers began to see a rapid decline, with their population now nearing zero.

Zebra mussels can filter the entirety of the Hudson in three to four days. This has had major effects on the Hudson’s ecology according to involved scientists.

“Ecosystems are impacted by zebra mussels through the alteration of the microscopic invertebrate community,” said Pearson. “The mussels filter water in a way that often leads to change in the clarity of a water body. That clarity can completely alter the plant and animal communities that are found in those water bodies. It can take years for an ecosystem to re-establish or rebalance once that’s occurred.”

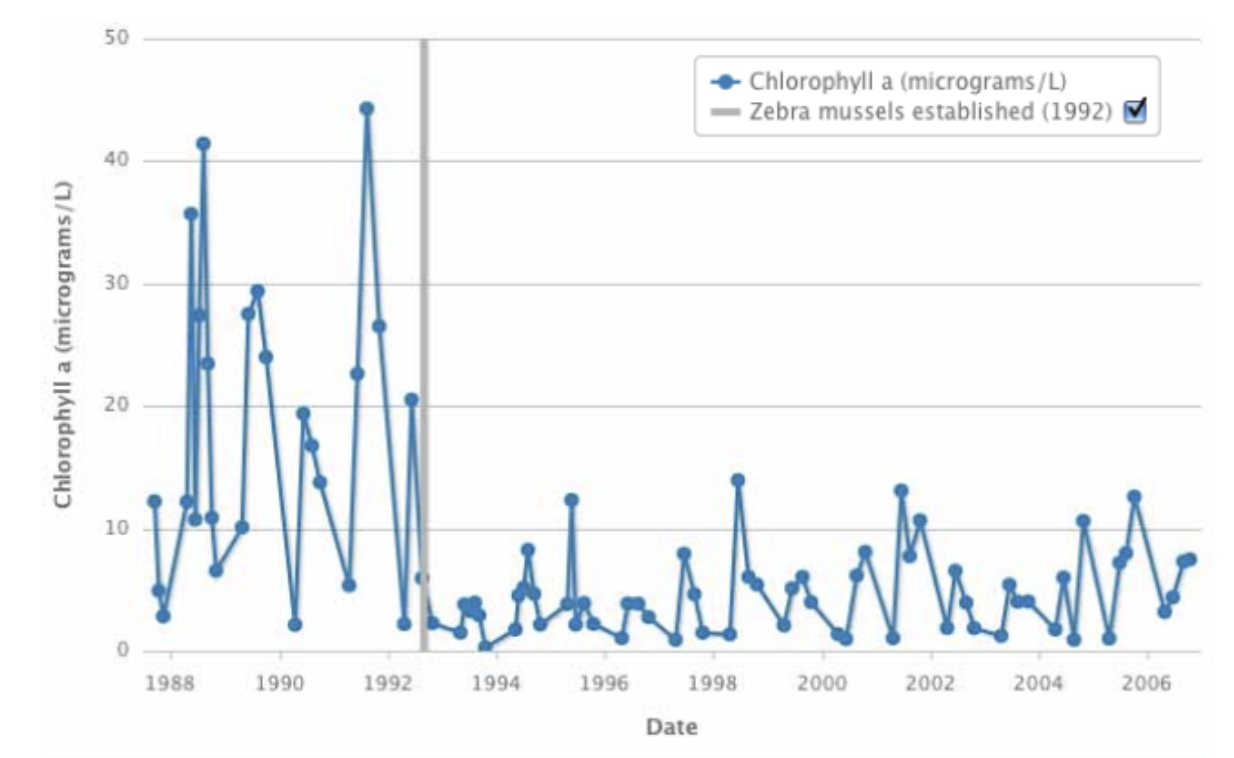

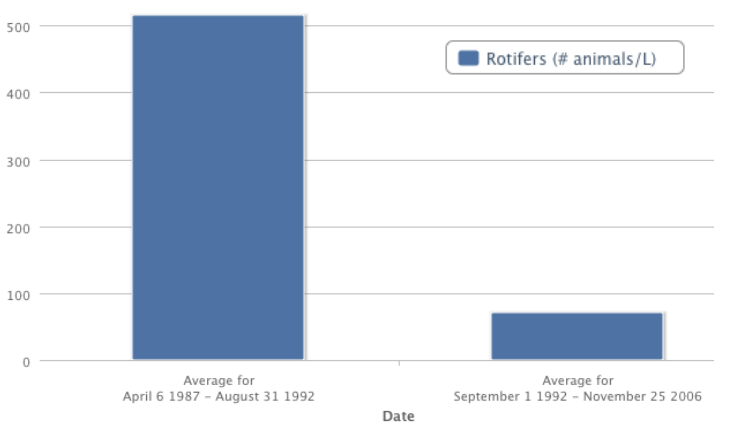

The process of filtering directly affects the number of essential microorganisms, such as phytoplankton and microzooplankton, populating a body of water. The zebra mussels have caused the Hudson’s phytoplankton and microzooplankton respective populations to decrease by 80% and 90% respectively since they were first introduced, according to the Cary Institute, a scientific research institute focused on advancing ecological knowledge and awareness.

PHYTOPLANKTON POPULATIONS IN HUDSON OVER 18 YEARS, GRAY LINE SYMBOLIZING INTRODUCTION OF ZEBRA MUSSELS (GRAPH PROVIDED BY CARY INSTITUTE).

MICROZOOPLANKTON POPULATIONS IN HUDSON OVER 14 YEARS AFTER INTRODUCTION OF ZEBRA MUSSELS (GRAPH PROVIDED BY CARY INSTITUTE).

Dr. Dianne Greenfield, a marine biologist and Associate Professor at the Advanced Science Research Center at the Graduate Center of CUNY, spoke to the health and impact of the plankton populations in New York water channels.

“They’re the base of aquatic food webs, I view them as sentinels of change,” said Dr. Greenfield. “Whether you’re talking about streams, lakes, coasts or the open ocean, their growth and productivity is affected by light, nutrients, temperature and their interactions amongst other organisms in the water.”

Zebra mussels are a nightmare for plankton populations due to their rapid feeding cycles. Additionally, they release harmful byproducts and prevent sunlight from reaching essential water vegetation, usually because they are covered by colonies.

This has also led to a major decline in other river organisms such as native fish and mussel populations that fed on the planktons as a primary food source.

“This decay and accumulation of biomass will rain down to the bottom of the water body, the bacteria that live there will consume it through the process of respiration,” added Dr. Greenfield. “This can lead to what we call hypoxia, which is dangerously low oxygen levels. This can impair fishes and other wildlife, so that they will either die or move somewhere else.”

Open-water fish such as the shad and herring both suffered as a result of the zebra mussels’ introduction, while littoral fish like sunfish migrated and prospered. Essentially, the mussels consumption levels coupled with their rapid multiplication and deposits of harmful biomass have completely altered the inhabitants and ecology of the Hudson River.

The mussels are also infamous for clogging water supply pipes and obstructing valves which can lead to noxious tastes and smells in treated water. These areas provide protection and a constant food supply for colonies to sustain. This, in turn, leads to millions in economic burden for maintenance and control.

“Financially speaking, zebra mussels cause an increase in the frequency of maintenance to different infrastructure,” said Pearson. “They can clog large intake pipes as well as smaller diameter pipes within pumps or mechanical pools. This type of maintenance costs industries and drinking water departments greatly on an annual basis.”

Since their arrival in North America, zebra mussels have caused more than an estimated $1 billion in damage and repairs by attaching to pipes and ruining infrastructure.

However, in recent years numerous initiatives have been introduced to limit the spread of the species.

“So there are a number of programs here just in New York to prevent the spread of aquatic invasive species, and zebra mussels are among the most prominent species we’re concerned with,” said Pearson. “Those are typically dealt with by the Watercraft Steward Inspection program. They work to prevent the spread of zebra mussels and other aquatic invasive species. They inspect boats before they’re launched.”

The program helps follow mandates for boat drivers to clean, drain and dry their vessels and gear before entering New York water channels.

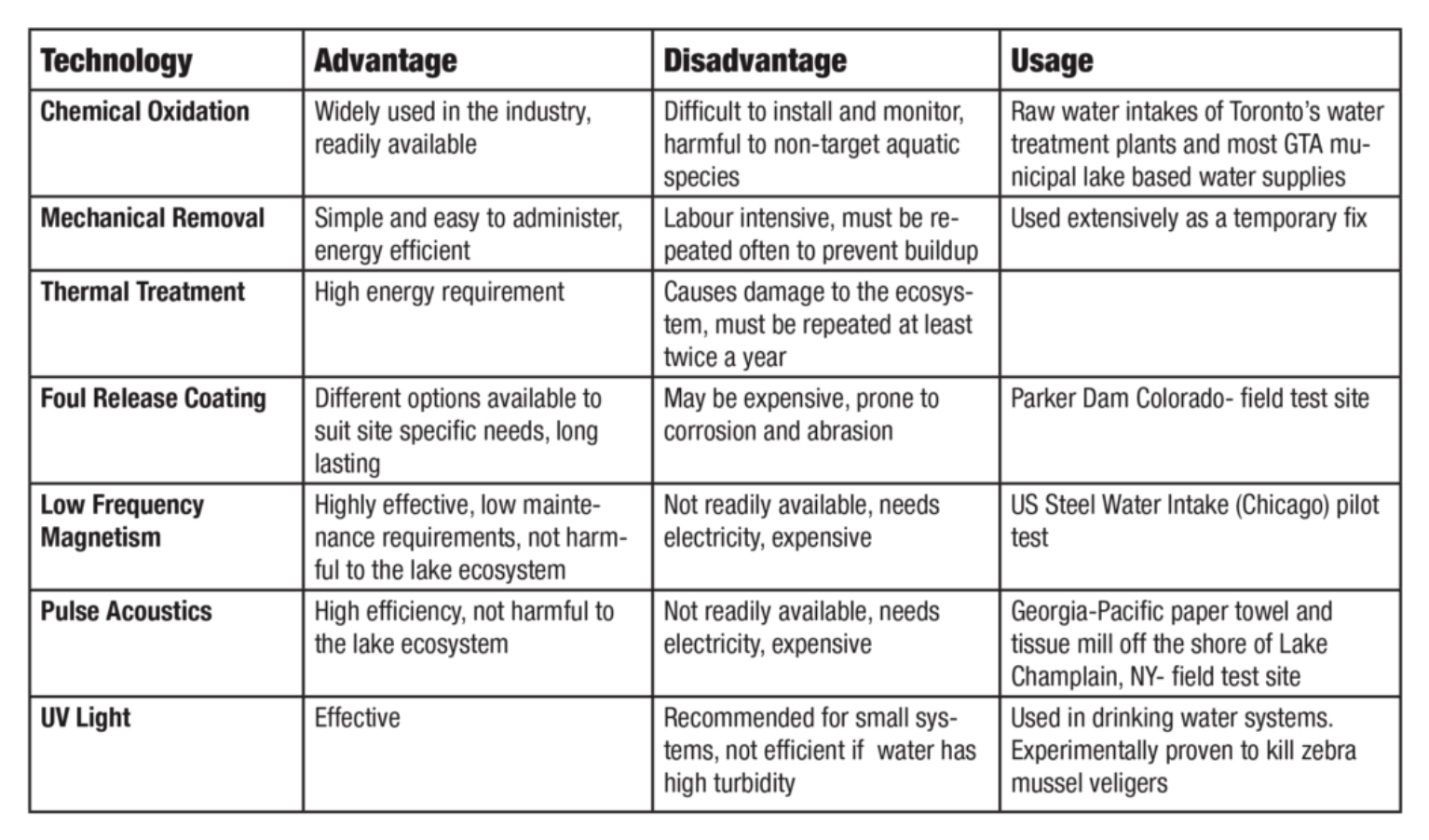

Additionally, environmental companies have begun implementing more hands-on methods, both of prevention and removal. Practices involving chemical oxidation, mechanical removal, thermal treatment, UV light and more have all been utilized and have shown to be effective. (Methods and treatment provided below)

GRAPH PROVIDED BY CARY INSTITUTE

Overall, the zebra mussels pose a serious threat to any water body upon their introduction, with the Hudson serving as a prime example.

It does appear the Hudson is making progress in recent years thanks to continued environmental efforts and natural ecological processes.

According to the Sustainable Hudson Valley effort, in 2011 researchers found that the annual survival rate of zebra mussels was 99% lower compared to their original survival rate when they were introduced in the 90s. The rate at which they filter freshwater has reportedly also dropped by more than 82%.

Other scientists speculate that the rise of natural predators such as the sturgeon, blue-crabs and ducks have also contributed to the observed decline in recent years. Their life spans on average have also dropped from seven to two years.

“It’s really important that all users of water bodies check for any aquatic invasive species on their fishing gear or boats, to prevent the spread of invasive species to new water bodies by being really persistent,” said Pearson.