Floating Gardens in NYC

By Shreya Suresh

It is around four o’clock on a Thursday afternoon in Red Hook, Brooklyn. The ship container-turned-workspace is now filled with a dozen students from the Harbor Middle School. The students, bundled in thick puffers, are circled around a wooden hexagonal base filled with corks and partially netted. Their small hands are busy as Maria Orejuela and Diana Paredes from the RETI Center give instructions that the children, for the most part, readily follow.

The garden’s architectural base is inspired by a lily pad, mimicking an integrated ecological system that supports life along a deep sectional column. The base is filled with corks for their buoyancy, and then patches of a local species of grass are insulated and placed in the cork. Finally, a net is placed over the structure, which is now ready to be set afloat.

A handful of students are eagerly sifting through the corks, plucking out any of the synthetic pieces they spot. Two enthusiastic seventh graders are taking a supervised go at the power drill, to fasten any loose pieces of wood. The rest are busy insulating bunches of grass with wool and burrowing them into little pockets in the cork. The floating garden is almost complete and will soon be ready to be placed on the water amid its seven other companions that are already afloat.

Image by Shreya Suresh

“This is the first time we have this amount of gardens,” explains Orejuela. “The idea is that they die in the winter and they’ll come back in the spring, but this is an experiment, so we’re gonna see what happens.”

The children are at ease in the RETI center. It’s just a 15-minute walk from the school. As they finish the assembly of the garden, hot chocolate is passed around as a sweet reward for their hard work. The children gulp their drinks down quickly and pose for a few photos before they take their leave.

When you think of New York City, an image of hexagonal floating gardens on the waters of Brooklyn doesn’t usually come to mind. Most New Yorkers live in small apartments that cost more than a mansion in Texas. But escape is possible. Well, at least short moments of escape.

The average New Yorker can find escape in urban gardens. Escape from cramped space. Escape from $40 Chinese takeout. Escape from loneliness.

The RETI Center is just one example of a growing number of organizations in New York City that are striving to increase the city’s green space through innovative urban gardens. Urban gardens can serve one of several different purposes: aesthetic, functional, ecological, and educational. The aesthetic purpose of an urban garden is fairly self-explanatory. A space to escape the everyday congestion of the densely populated cityscape, to take in a deep breath of fresh air, and, once relaxed, a few pictures for social media. More often than not, most urban gardens will fall under this category. Nature can’t escape poetry, and poetry can’t escape nature, and if it hasn’t been underscored enough already, New Yorkers want to escape the four walls of their apartments and cubicles to see vines growing far beyond their reach.

Urban gardens can also help alleviate the effects of climate change in cities: reducing the urban heat island effects of manmade infrastructure, keeping more carbon from being released, reducing flood risk, and supporting wildlife diversity. According to a study conducted by the WHO, increasing the number and quality of green spaces has the potential to mitigate short-lived climate pollutants that produce a strong global warming effect and contribute significantly to more than 7 million premature air-pollution related deaths annually.

An example of the functional purpose of an urban garden might be generating local produce. A great example are urban gardens that supply produce to neighborhoods through Community Supported Agriculture (CSAs). Leora Nevins, a longtime resident of Crown Heights, gets her weekly produce through the Crown Heights CSA and the Prospect Heights CSA. “I had never had scallions so sharp, nor yams so sweet—tomatoes so bright—as the CSA vegetables,” she raves. But it isn’t just the quality of the produce that attracts locals like Nevins. “It also helps me connect to my neighborhood community because it’s volunteer led and I feel like I’m connecting with other people in the city who care about fresh food and supporting small farmers who prioritize organic practices,” she says.

The floating gardens at the RETI Center and Grow NYC’s teaching garden are two examples of urban gardens that have multiple focuses, with education at the heart. The floating gardens serve then an ecological purpose of helping to support the regeneration of aquatic habitats in urban contexts that are suffering from environmental degradation. But the collaborative and easy assembly of the gardens help in making them effective teaching tools. Similarly, GrowNYC’s teaching garden located on Governors Island uses the space to teach students the practical skill of farming, while also generating produce for consumption.

Image by Shreya Suresh

The more innovative urban gardens can be, the more purposes they can serve in the limited spaces they occupy. Innovation can look as complicated as the architectural underpinnings of the floating gardens, but also as simple as creating a steady community engagement plan through partnerships with schools.

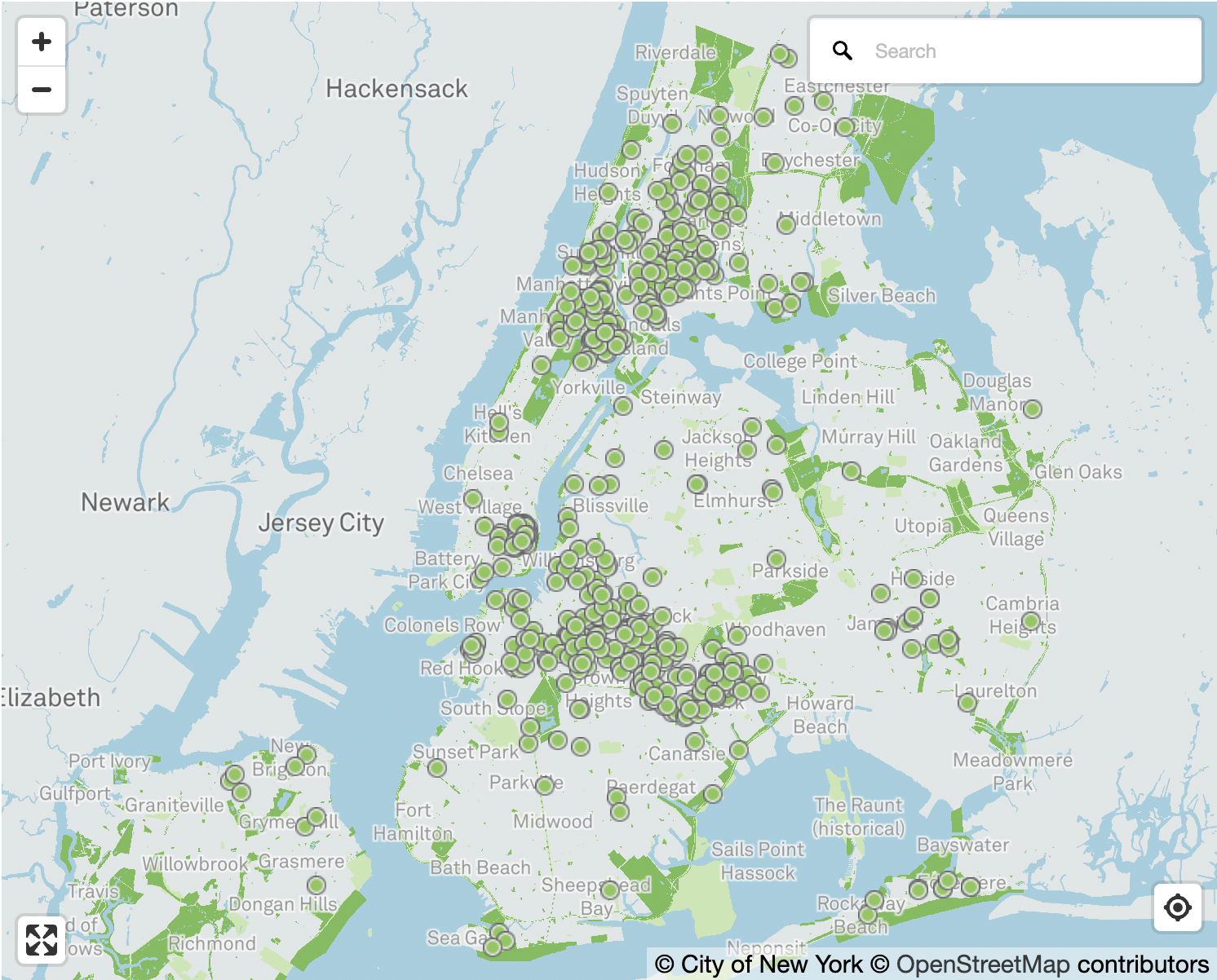

One of the biggest governmental programs around urban gardens is the GreenThumb, by the NYC Parks Department. GreenThumb, which was established in 1978, is the nation’s largest urban gardening program. The program sustains over 550 community gardens across all five boroughs and supports over 20,000 volunteer gardeners throughout New York City. The composition of each garden varies; some are smaller, with around 10 volunteers, while others have more than 100 regular volunteers supporting the garden.

The initiative started in response to the city’s financial crisis in the 1970s. The city’s taxpayer base collapsed, heavy industry left, and many middle class residents decamped for the suburbs. This resulted, in part, in an abandonment of land. The majority of GreenThumb gardens were these vacant lots that were in very poor shape and then renovated by the hard work of volunteers.

Green Thumb today is a space for community members to find a small square of land to tend to, in a city where backyards are a rarer sight than in-unit laundry. Isak Mendes, deputy director of Green Thumb, says that the program helps to “provide community members to garden in these spaces and that they have autonomy in these spaces.”

Courtesy of NYC Parks Department

Mendes, who grew up in Park Slope, Brooklyn, was drawn to working for Green Thumb because of his own personal experiences with urban gardens growing up. “I’ve been with Green Thumb for nine years, but I’ve been in the community garden scene for my entire adult life,” he says. “The way I got connected was because I lived close to a community garden in Park Slope and my mother would put food scraps on the sink and I would hate that and I was like ‘we gotta throw this out.’ But my mother saved them because she would wait to put them in the compost at the community garden nearby. As a kid, I would go down there with her and it was just beautiful. You just walk into this oasis. I knew at a young age this is what I wanted to do.”

Mendes’s experience echoes organizers’ at not only Green Thumb, but many other urban garden initiatives across the city. “It is bringing this oasis all over the city to people who may not have access to fresh food or nature. It provides all of that: green spaces, social spaces and learning spaces.”

The negotiation and maintenance of green space has historically been a task for both private and public organizations in New York City. But at the heart of sustaining and expanding urban green spaces will always be the community. The mouths that fill their hunger with local produce; the tired feet that take refuge on the grassy knoll; and the little hands of middle schoolers that help plant and build for the future. The relationship between the gardens and the community are intrinsically intertwined, symbiotically helping to grow a greener future.

Zebra Mussels: A Hudson River Crisis

By Prabhat Seelamsetti

The Hudson River is one of North America’s most iconic and well known waterways. Roughly 30 years ago, it was also one of the most ecologically diverse aquatic ecosystems on the continent.

Since then, the river has dealt with a large number of sanitary and ecological issues, including pollution and salinity. One ecological challenge, in particular, has gone under the radar for decades: the rise of the zebra mussel.

Steven Pearson, the head of aquatic invasive species at the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC), has studied the mussels for years and spoke to how their minuscule size masked a major environmental threat.

”They’re very small, not very many people even know that they exist,” Pearson said. “However, those who live in, recreate near, or manage submerged infrastructure in areas where zebra mussels are, they know about this problem and they’re very concerned.”

Originally native to the Eurasian region, zebra mussels have been classified as an invasive species to the North American region.

They were first introduced to the continent in 1981 by attaching to vessels from their native regions and dispersing upon arriving in the new water bodies. This has been pinpointed as their primary means of invading foreign environments.

They did not make an appearance in the Hudson River until 1991, but upon being introduced they quickly multiplied and wreaked immediate havoc on the environment.

While the organisms are seemingly harmless, spanning less than 5 cm in size, they can reproduce at unbelievably quick rates and have drastic environmental effects in a foreign ecosystem.

“Zebra mussels cannot be eradicated from a landscape,” said Pearson. “In small, isolated water bodies an infestation could be eradicated, but usually once they’re introduced to water bodies they become a part of the invertebrate community and vastly alter the ecology of the system. Essentially on a broad landscape, nothing can really be done once they’re introduced.”

In one year, a single mature female can produce more than two million eggs while a single male can release an estimated two hundred million sperm. This allows for mussel colonies to form and span across a riverbed very quickly and eventually number within the billions across the entire system.

Once colonies are established a number of issues can arise. The waste that mussels produce is toxic to freshwater environments and limits oxygen levels while altering the surrounding water’s pH concentration.

The Hudson’s native “pearly mussels,” which once numbered more than one billion, only filtered the river every 2-3 months. This minimal level of filtering created the ideal conditions for the native fish, plankton and bacteria populations to thrive. After 1991, their numbers began to see a rapid decline, with their population now nearing zero.

Zebra mussels can filter the entirety of the Hudson in three to four days. This has had major effects on the Hudson’s ecology according to involved scientists.

“Ecosystems are impacted by zebra mussels through the alteration of the microscopic invertebrate community,” said Pearson. “The mussels filter water in a way that often leads to change in the clarity of a water body. That clarity can completely alter the plant and animal communities that are found in those water bodies. It can take years for an ecosystem to re-establish or rebalance once that’s occurred.”

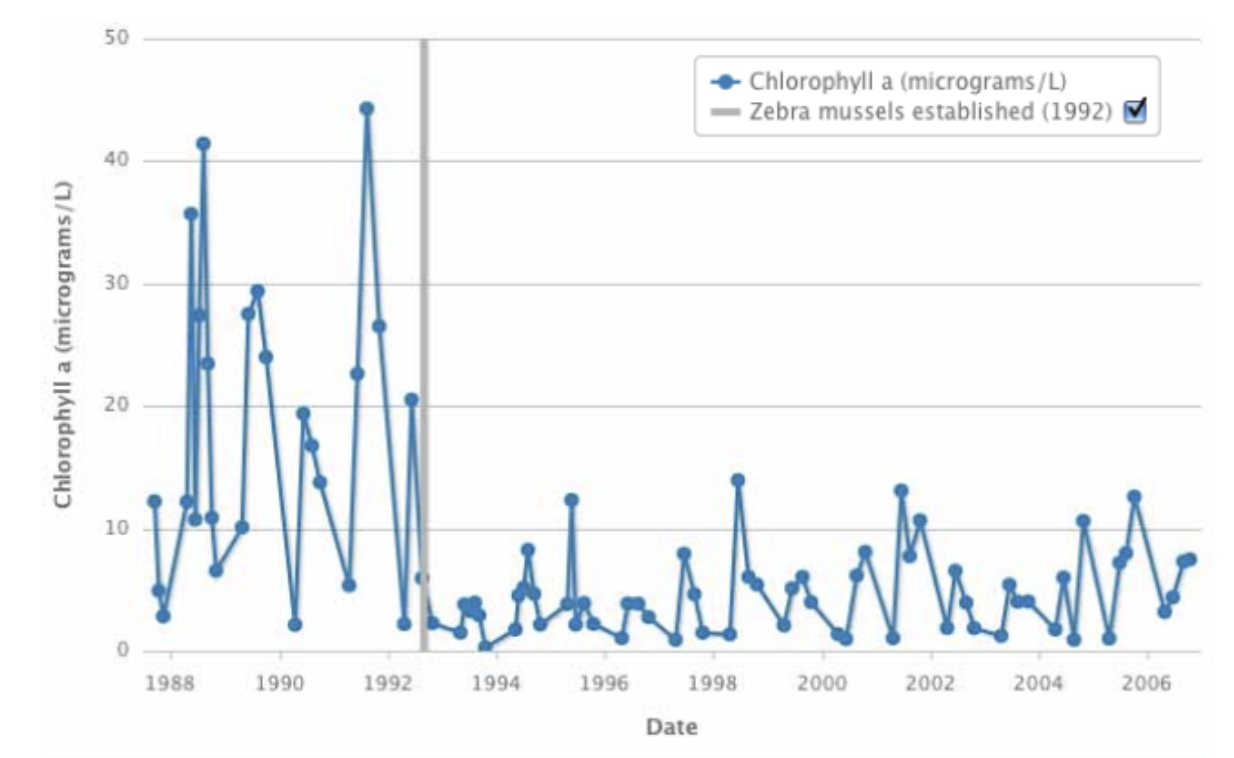

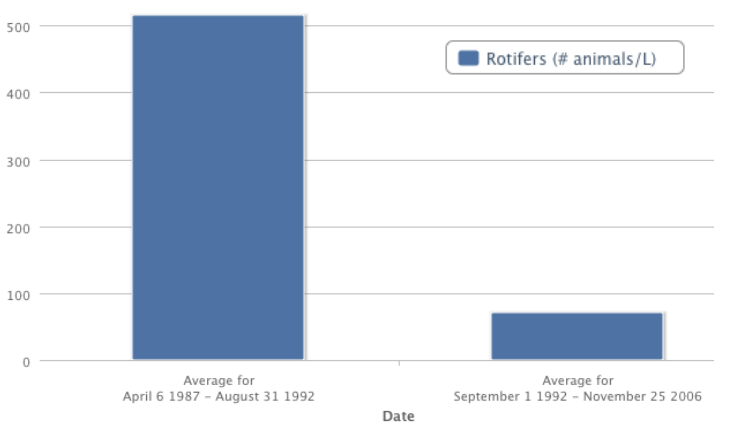

The process of filtering directly affects the number of essential microorganisms, such as phytoplankton and microzooplankton, populating a body of water. The zebra mussels have caused the Hudson’s phytoplankton and microzooplankton respective populations to decrease by 80% and 90% respectively since they were first introduced, according to the Cary Institute, a scientific research institute focused on advancing ecological knowledge and awareness.

PHYTOPLANKTON POPULATIONS IN HUDSON OVER 18 YEARS, GRAY LINE SYMBOLIZING INTRODUCTION OF ZEBRA MUSSELS (GRAPH PROVIDED BY CARY INSTITUTE).

MICROZOOPLANKTON POPULATIONS IN HUDSON OVER 14 YEARS AFTER INTRODUCTION OF ZEBRA MUSSELS (GRAPH PROVIDED BY CARY INSTITUTE).

Dr. Dianne Greenfield, a marine biologist and Associate Professor at the Advanced Science Research Center at the Graduate Center of CUNY, spoke to the health and impact of the plankton populations in New York water channels.

“They’re the base of aquatic food webs, I view them as sentinels of change,” said Dr. Greenfield. “Whether you’re talking about streams, lakes, coasts or the open ocean, their growth and productivity is affected by light, nutrients, temperature and their interactions amongst other organisms in the water.”

Zebra mussels are a nightmare for plankton populations due to their rapid feeding cycles. Additionally, they release harmful byproducts and prevent sunlight from reaching essential water vegetation, usually because they are covered by colonies.

This has also led to a major decline in other river organisms such as native fish and mussel populations that fed on the planktons as a primary food source.

“This decay and accumulation of biomass will rain down to the bottom of the water body, the bacteria that live there will consume it through the process of respiration,” added Dr. Greenfield. “This can lead to what we call hypoxia, which is dangerously low oxygen levels. This can impair fishes and other wildlife, so that they will either die or move somewhere else.”

Open-water fish such as the shad and herring both suffered as a result of the zebra mussels’ introduction, while littoral fish like sunfish migrated and prospered. Essentially, the mussels consumption levels coupled with their rapid multiplication and deposits of harmful biomass have completely altered the inhabitants and ecology of the Hudson River.

The mussels are also infamous for clogging water supply pipes and obstructing valves which can lead to noxious tastes and smells in treated water. These areas provide protection and a constant food supply for colonies to sustain. This, in turn, leads to millions in economic burden for maintenance and control.

“Financially speaking, zebra mussels cause an increase in the frequency of maintenance to different infrastructure,” said Pearson. “They can clog large intake pipes as well as smaller diameter pipes within pumps or mechanical pools. This type of maintenance costs industries and drinking water departments greatly on an annual basis.”

Since their arrival in North America, zebra mussels have caused more than an estimated $1 billion in damage and repairs by attaching to pipes and ruining infrastructure.

However, in recent years numerous initiatives have been introduced to limit the spread of the species.

“So there are a number of programs here just in New York to prevent the spread of aquatic invasive species, and zebra mussels are among the most prominent species we’re concerned with,” said Pearson. “Those are typically dealt with by the Watercraft Steward Inspection program. They work to prevent the spread of zebra mussels and other aquatic invasive species. They inspect boats before they’re launched.”

The program helps follow mandates for boat drivers to clean, drain and dry their vessels and gear before entering New York water channels.

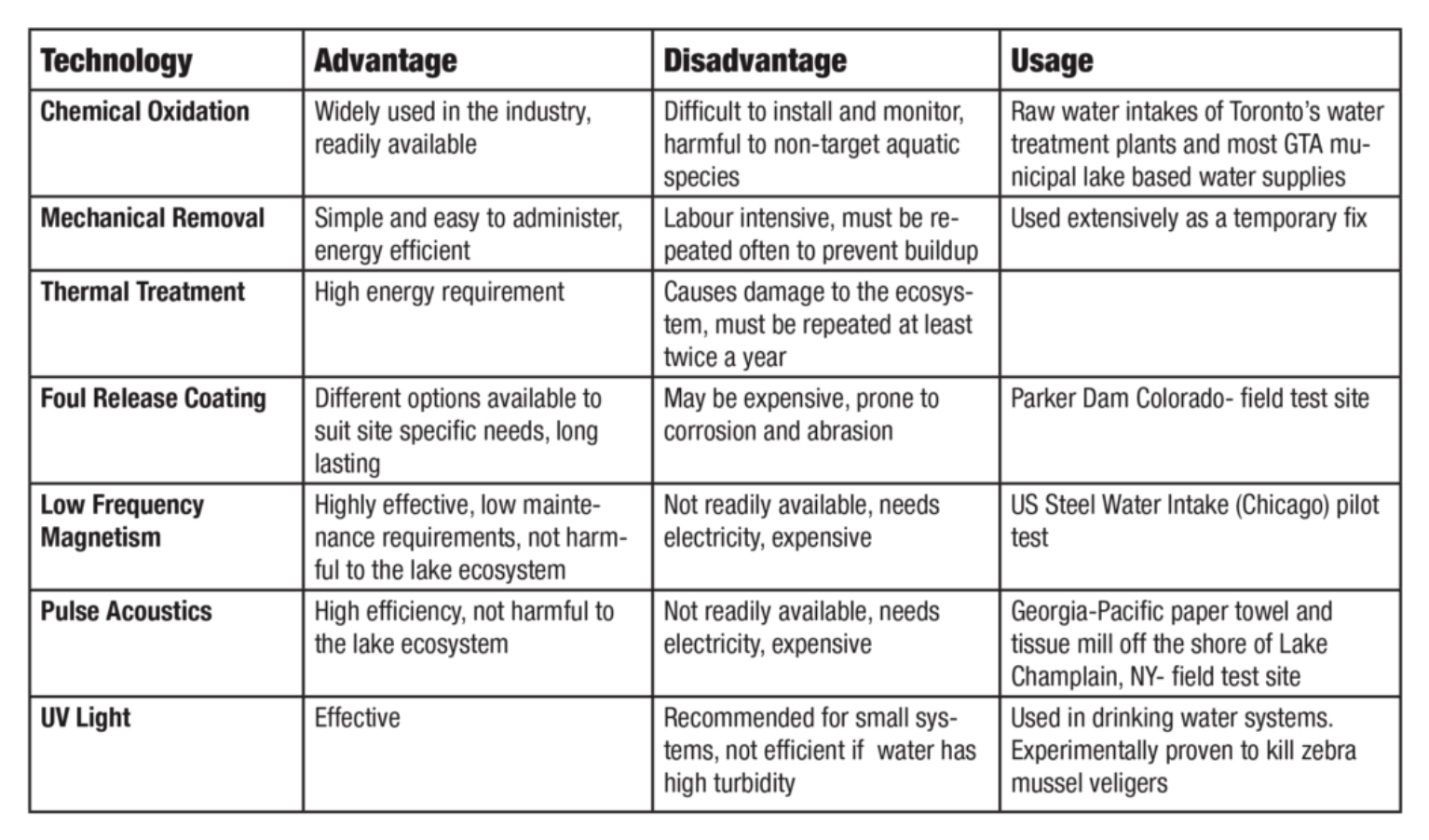

Additionally, environmental companies have begun implementing more hands-on methods, both of prevention and removal. Practices involving chemical oxidation, mechanical removal, thermal treatment, UV light and more have all been utilized and have shown to be effective. (Methods and treatment provided below)

GRAPH PROVIDED BY CARY INSTITUTE

Overall, the zebra mussels pose a serious threat to any water body upon their introduction, with the Hudson serving as a prime example.

It does appear the Hudson is making progress in recent years thanks to continued environmental efforts and natural ecological processes.

According to the Sustainable Hudson Valley effort, in 2011 researchers found that the annual survival rate of zebra mussels was 99% lower compared to their original survival rate when they were introduced in the 90s. The rate at which they filter freshwater has reportedly also dropped by more than 82%.

Other scientists speculate that the rise of natural predators such as the sturgeon, blue-crabs and ducks have also contributed to the observed decline in recent years. Their life spans on average have also dropped from seven to two years.

“It’s really important that all users of water bodies check for any aquatic invasive species on their fishing gear or boats, to prevent the spread of invasive species to new water bodies by being really persistent,” said Pearson.

Wildlife on the Waterway

A Changing Tide

By E. E. Oliver

Contrary to popular belief, New York’s waterways aren’t dirty, disease-riddled, and dead. Dr. Tim Gilman-Sevcik, the executive director of the RETI Center, a Gowanus Bay-based nonprofit, says New York needs its citizens to embrace the waterways’s biodiversity for its own health.

“We were keeping up for a thousand years, that is now over,” he says. “In order to adapt to the new climate and the new climate paradigm we have to change the way we do things.”

The way in which the RETI Center is attempting to alter this preconception has been the introduction of floating habitats. These “floating gardens” made of reclaimed cork and wood, and planted with native marsh grass, are a pilot of how biodiversity could be supported on the water.

The RETI Center’s floating gardens in Gowanus Bay, Red Hook

“It’s a resting place for birds, it’s a home for other species that are living within the corks, it’s a place for plants to grow,” says Diana Paredes, who has been working to build and deploy these gardens, “the idea behind it is that they’re going to support the whole water column.”

Dr. Gilman-Sevcik sees these gardens, still in the pilot stage, as a way to tempt New Yorker’s back towards the biodiversity that exists in their waterways. “I’m not saying these gardens are going to change the world, I am saying it’s a positive thing you can do with your hands…that is going to have an impact,” he says. “Someone’s going to stop by, look over the railing and say ‘that’s cool, I’m gonna do that too,’ and that’s where the impact grows.”

Views such as this are not hard to find in the community-based groups and nonprofits that line the harbor of New York. Many are dedicated to integrating biodiversity back into the concrete and steel that has sprung up over the preceding centuries to delineate and manage New York’s water. But this is no small task: they are up against hundreds of years of infrastructure and urban planning that have made the waterways polluted and inaccessible.

This urban planning has much to do with why many New Yorkers are unaware or ambivalent of the waterways that surround them. New York has been built in such a way that it is almost easy to forget that Manhattan is an island. Even easier to forget that much of Brooklyn and Manhattan is built on wetlands at least partially filled in by dead animals, and that planes coming into land at JFK Airport fly over a picturesque tidal salt marsh.

More than four centuries of development have made the New York and New Jersey Harbor Estuary one of the most intensively reconstructed waterways in the world. Wetlands have been replaced by concrete, inlets by canals. Where rivers once meandered, they now run dead straight, another artery in the beating heart of New York. The water gave the industries of the growing city speedy highways on which to transport their products, and a seemingly never-ending free trash can. Industrial and economic growth was the order of the day, and for 400 years the waterways seemed happy to enable this.

A closer look at certain spots around the estuary anytime between 1700 and the present day may have made you question whether this relationship was mutually beneficial. Much of the water surrounding New York might have looked effectively dead. Lacking oxygen, full of dangerous industrial chemicals, let alone the raw sewage: it would be difficult to think of a less hospitable environment for aquatic life.

However, the past 30 years has seen the beginnings of an ecological transformation in the waterways. A slowdown in industry, coupled with community-based and federal clean-up projects, like the Clean Water Act of 1972 and the designation of three water bodies as Superfund sites to remove industrial pollutants, has seen much of the estuary’s biodiversity bounce back.

The Hudson River is a particularly good example of this. Where once severely polluted waters hosted little to no macroscopic marine life, there now exists a fully functioning ecosystem, with sturgeon more than 14 feet long detected in the waters of the Hudson, a good indicator of healthy ecology.

Dr. Chester Zarnoch, head of the Benthic Ecology Lab and professor in the Department of Natural Science at CUNY, is a visiting researcher at the Hudson River Park, and is determined to incorporate science into habitat creation. “We really need to integrate science into these construction projects,” he says, “because there’s a lot of capital funding to build things, but there’s not a lot of funding to monitor, to do experiments, to learn from construction projects and be able to do them better in the future.”

He and his lab are working to further regenerate the Lower Hudson, and demonstrate the value of science-led habitat creation, by constructing a native salt marsh in the park. “They’re really some of the most important habitats,” he says. “They provide a number of really important functions, they’re really important in nutrient cycling … fish habitats … they attenuate waves to protect property, and they do a really great job at sequestering carbon.”

This nutrient cycling in particular underpins marine ecology, making the marsh habitats important to waterbody health. In fact, according to Dr. Zarnoch’s research, some natural marshes in New York have been shown to remove 17% of the nitrogen entering their wider waterbody. This nitrogen removal is of particular importance to marine health as it protects the waterway from the occurrence of harmful algal blooms.

Dr. Dianne Greenfield, an Associate Professor at the Advanced Science Research Center at CUNY, and another visiting researcher working in the Lower Hudson, is studying these harmful algal blooms.

Dr. Greenfield is trying to find just how much nitrogen from combined sewage overflow affects the diversity and ecology of phytoplankton; tiny, photosynthetic organisms that require one or more forms of nitrogen to grow. “Regardless of which waterway you’re talking about, it’s really a story about nitrogen,” she says. This is important for a few reasons. One being that phytoplankton are the basis of the marine food web: they are key to supporting other marine life. However, a subset of species can form harmful algal blooms when they grow out of control. This can cause negative human health and/or ecosystem impacts, like shellfish poisoning and habitat impairment.

This makes understanding what affects phytoplankton of tantamount importance in restoring marine ecology and habitats in New York. Nitrogen is often introduced into the water from urban water runoff, mainly sewage. So, a greater concentration of sewage generally means more nitrogen, which can mean more problems for the ecosystem.

CSO or Combined Sewage Overflow is the term used to describe water and raw sewage that is diverted into New York’s waterways when the system becomes overwhelmed. In New York this can happen very quickly as rainwater and sewage share the same system. “It floods super fast now, like within 15 to 30 minutes if there’s moderate rainfall,” says Gary Francis, captain of the Gowanus Dredgers Canoe Club, a community group that advocates for biodiversity and access to the Gowanus Canal. “The sewer pipe has been doubled in size … the idea was that it would solve flooding up on 4thAvenue, which is a problem, but the solution has been to put in bigger pipes that send [CSO] into the canal much faster.”

Knock-on effects from CSO can exacerbate ecological problems in New York’s waterways. Harmful algal blooms have been spotted in Newtown Creek, and the Gowanus Canal has experienced three mass fish die-offs this summer. Die-offs, the Dredgers believe, were due to low dissolved oxygen in the water, caused by a combination of CSO and the temporary deactivation of the Flushing Tunnel, which brings fresh water into the canal. However, CBS News reported that a spokesperson from the Department of Environmental Protection said that fish-kills were common, and not directly linked to the high amount of CSO detected in the canal around this time.

Whatever the cause, before the fish kills, these past few summers have been the first time Francis can remember seeing so many of these fish in the canal. The Gowanus Canal has recently undergone a massive dredging program as part of its’ Superfund status to remove highly contaminated sediment. The water is cleaner than it has been in centuries.

The contrast in water quality between the dredged and un-dredged areas in the Gowanus Canal.

However, this has come at a cost to the canal’s intertidal habitats. “Before the dredging began there was an enormous amount of biodiversity along the edges of the canal,” says Andrea Parker, the executive director of the Gowanus Canal Conservancy, “we are now looking at a sterile box of water… this is the least alive the canal has ever been.” The wooden bulkheads that once lined the canal are being replaced with steel; another part of the remediation effort, to prevent the seepage of toxic coal tar from the Gowanus shoreline back into the canal. However, the wooden bulkheads provided vital habitats for filtering organisms such as ribbed Atlantic mussels, aquatic plants, and other small shellfish. These in turn provided food and spaces for some fish nurseries to thrive, even in the severely polluted water.

Although a necessary step in the remediation of the canal, this loss of habitat has required the community groups in Gowanus to collaborate closely to ensure that the biodiversity can return in the same, or even greater quantities. The first step of this for the GCC was to quantify what would be lost. A “BioBlitz” from 2017-2021 found more than 500 species calling the canal home, a perhaps surprising number for a canal the EPA had called “one of the nation’s most seriously contaminated water bodies.” The Gowanus Dredgers also began surveying the numbers of Atlantic ribbed mussels living in the remaining wooden bulkheads, in one section they recently found over 2500 Atlantic mussels, some still thriving while covered in coal tar.

This proof that viable habitat would be lost by the replacement of the wooden bulkheads has prompted these groups to try numerous ways to integrate habitat into the steel. Francis, an ornamental plasterer by trade, began designing mussel habitats that could be hung from the bulkheads. “I’m interested in that vertical, hardened shoreline because it’s everywhere around the city, and it’s only increasing,” he says. Although currently unable to install his habitats in the Gowanus as the EPA remediation is under way, he has been able to install one in Newtown Creek. However, since it’s only recently installed, it’s unclear whether it can attract the mussels.

A mussel habitat designed by Francis to hang from steel bulkheads. Photo credit: Nicole Vergalla.

For Parker, habitat construction is what she and the GCC have been doing for more than a decade. In 2013 the GCC constructed a salt marsh along one section of the canal, together with a garden filled with other native plant species. When the BioBlitz was conducted, this constructed habitat was home to the majority of species found, 280 in total.

However, a bittersweet twist of fate meant that this site was dismantled to make way for a sewage tank to help prevent CSO into the canal. “The only time I cried was right there, right before it was demolished,” says Parker, “I poured my life and youth into those gardens.” Despite having to start from scratch, the resilience of the canal’s ecosystem after decades of contamination has made Parker optimistic about how biodiversity could rebound in the Gowanus after remediation is complete.

Although the long-term future of the Gowanus seems relatively rosy in terms of pollution, it is still to be seen whether the biodiversity will return in the same way as before. However, this kind of community involvement, and commitment to continued investment in scientific monitoring, is the one thing repeated over and over as often lacking, but also absolutely key to successful and biodiverse waterways in New York. As Dr. Gilman-Selcik puts it, “the sense of enthusiasm, interest, engagement you create by doing [community involvement], in the sense of stewardship of the natural resources, is exponential.”