Battle Over Boilers

By Maria Fernanda Cestero Muñiz

Kaitlyn Quach believed talk about climate change was all “doom everywhere” and felt powerless. She attended the School of Visual Arts as part of her honors program. One of her courses required her to read Greta Thunberg’s The Climate Book and it changed her view completely.

She suddenly felt empowered.

“Even though I’m one person, I can still do something,” said Quach. “There should be no delay in climate change action. We can’t do anything else if we can’t live on the planet.”

Inspired by Thunberg’s book, Quach started volunteering at environmental rallies. In 2021, she joined the nonprofit environmental organization, Food and Water Watch. On November 30, Quach, along with other members of the organization rallied for New York City’s “most ambitious plan” for climate change: Local Law 97.

Local Law 97 was included in the Climate Mobilization Act passed by the City Council in 2019 under Mayor Bill de Blasio which aims to make New York City carbon neutral by 2050.

More than two-thirds of the city’s greenhouse gas emissions are produced from physical buildings. The goal is to reduce the emissions produced by the city’s buildings 40 percent by 2030 and 80 percent by 2050.

Under Local Law 97, buildings over 25 thousand square feet must reduce their emissions by their allotted amount starting in 2024 or face a fine of $268 per ton of emissions over their designated standard.

Despite the stated aim to reduce the city’s contributions of greenhouse gases, Eric Adams, the current mayor, proposed a “good faith” effort allowing buildings a two-year extension on the 2024 deadline if they show an effort to reduce their emissions. The Adams administration is currently developing the criteria for how those efforts will be assessed.

“It’s [Local Law 97] important to me because it’s already a law and it made me upset Eric [Mayor Eric Adams] is puppeteering to billionaires,” said Quach. “It’s up to us to do something.”

Together with her organization and community members, Quach stood in solidarity in front of one of the entrances to City Hall pleading for council members to support their cause.

“Really, we saw it as a betrayal of public interest, but also as a real setback for the climate movement in general,” said climate activist and Food and Water Watch organizer David Vassar. “The mayor, very disappointingly, and the real estate industry seem not to care so much about the public interest, the community interest and the climate that our kids are inheriting.”

Vassar was among several people arrested at the protest for obstructing traffic.

“We need to get the word out and show our commitment to the skies,” said Vassar. “And I would do it again.”

And he did. On Dec. 6, Vassar attended a rally hosted by his colleague, and Brooklyn-based senior organizer of Food and Water Watch, Eric Weltman.

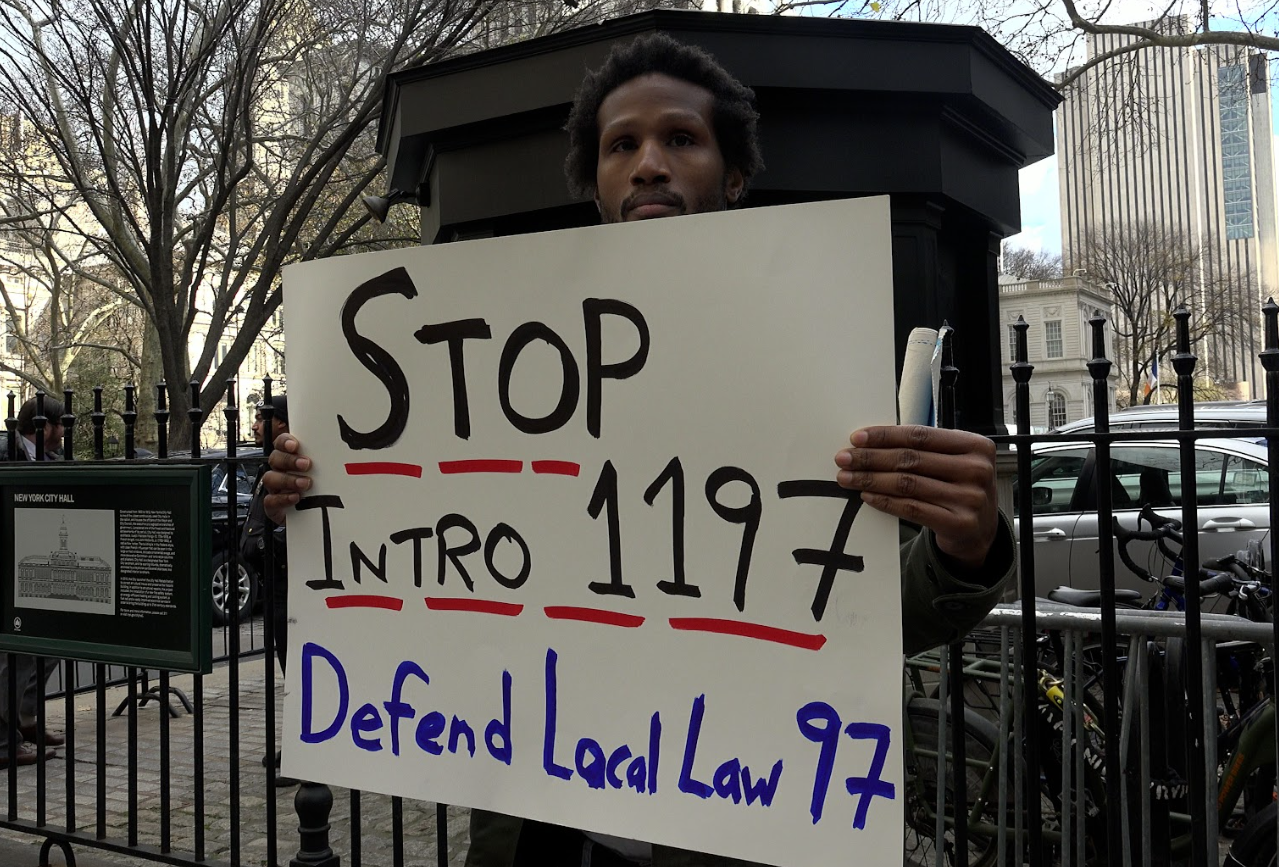

Rally attendee holds signs opposing 11-97.

City Hall was bustling with several protests, as Food and Water Watch, along with members of other organizations such as NYPIRG, stood by one of the entrances. Weltman encouraged members of the City Council to not support a newly introduced bill, 11-97.

The bill proposes to include green spaces while determining a building’s criteria for reducing emissions and will take into account if measures had been previously taken by buildings to reduce their emissions. It aims to weaken the criteria of Local Law 97 to accommodate co-ops and other complexes struggling to meet the target for cutting emissions.

Weltman has been involved in the nonprofit environmental organization for more than a dozen years. Fearing the consequences of climate change, Weltman is concerned about the planet his son will inherit.

“I have a son who’s very fearful about the future that portends for him and his peers as a consequence of climate change and I share his concerns for him and his generation,” he said. “Climate change is an existential threat to humanity.”

According to the city’s Department of Buildings, buildings in the five boroughs are complying with the emissions law at a higher rate than anticipated. Only 11 percent of buildings in the city have failed to comply with the regulations set for January 2024—half of which the city forecasted. Most of the buildings that are out of compliance are short between 10 and15 percent of their emission reduction goals. Many more buildings will be out of compliance for the 2030 reduction targets.

In order to meet the requirements, buildings will have to find the means to cut their emissions. Emission cuts can be linked to lighting, heating and cooling systems, and appliance usage. Other buildings will have to rewire their structures to comply or replace boilers, which can be costly.

“About 3,700 properties could be out of compliance and face over $200 million per year in penalties by next year,” according to a statement by the Real Estate of New York. “By 2030, over 13,500 properties could cumulatively face penalties as high as $900 million each year.”

Although many buildings comply with the “ambitious” goals for 2024, many buildings will be out of compliance by 2030. Some believe the efforts are too far-reaching.

The Linden Towers co-op #4 in Queens will be one of many apartment buildings that will fail to meet the 2030 goals. The three buildings which cumulatively hold 181 units are powered by two boilers running on natural gas which currently meet the criteria for the 2024 deadlines.

The current boilers were offered as an incentive by Con Edison. Con Ed had offered Linden Towers $96,000 if they remained on firm gas for four years, replacing their boilers that had run on dual fuel. Firm gas, or natural gas, is a relatively clean burning fossil fuel.

Con Edison stated they are incentivizing New Yorkers to reach the climate goals by building a “clean energy network”.

By 2030, the boilers will be out of compliance, causing more than $54,000 in fines in just one year, according to the Mayor’s Office of Climate and Environmental Justice. In addition to costly new electric boilers which may cost upwards of $100,000 each, the buildings will have to face rewiring in all units to be able to comply.

“Local Law 97 would affect us in the fact that we would have to buy new boilers that work on electricity only. That would be a tremendous cost to the co-ops,” said Arlene Fleishman, the president of the Linden Towers co-op board. “It would be a disaster. Where are we going to raise millions and millions of dollars if we took out new mortgages?”

A resident of the co-op for more than 60 years, Fleishman is concerned with the financial impact the law will have on her building and residents. Fleishman organized several meetings with the co-op board to discuss how the building is going to sustain incredible changes.

“If this [Local Law 97] forced us to put an electric boiler by a certain date, we would have to find the means,” said Fleishman. “The most affordable housing in this city is co-ops. I mean, we would no longer be affordable.”

Linden Towers boilers which run on natural gas.

Although sympathetic to the cause, Fleishman is skeptical that the cost of a new boiler system and wiring will fall on all the residents, including herself . Showing letters she had printed for her residents in English and Chinese, Fleishman explained that she, along with others, do not know how they can come up with the funds necessary to meet the criteria.

Fleishman hopes council members will pass intro 11-97, which will help her building accommodate the criteria for Local Law 97 and help keep her building affordable for her residents.

“We’ve invested so many years to maintain the buildings and build an environment that we can all afford,” said Fleishman. “If we’re forced to make this, as written, it’s going to destroy all of us. Every co-op in this community will be destroyed.”

Along with other co-op presidents, Fleishman is encouraging their local city councilwoman to reflect on the financial impact the Local Law will have on affordable housing units across the city.

“A two-year extension will do nothing,” said Fleishman. “I know some city council members support what’s going on- we all do. We all want to reduce carbon emissions. We all want to live in a safe environment … but it can’t be done like this.”

The Electric School Bus: Drive to Future

By Ruonan Jiang

Lauren Kesner O’Brien’s daughter, Alea, is applying to a high school in Manhattan where she will take a school bus to commute. Reflecting on Alea covering her nose and frowning after walking behind diesel exhaust, O’Brien worries about whether the school transportation would harm her daughter’s health in the pursuit of education. “A lot of my children’s friends have asthma, and they’re just exposed to a lot of vehicle emissions walking around the city,” she says. “School buses seem particularly poignant because they are made to protect kids, take kids to school. At minimum they should be clean.”

Alea covers her nose because of diesel exhaust. Photo by Ruonan Jiang.

In New York State, more than 2 million students ride school buses every year. Around 50,000 school buses, which is 10% of the nation’s fleets, are used to transport children safely. However, since most of them are diesel-powered vehicles, they emit greenhouse gases including CO2 that not only contribute to global warming but also have adverse effects on children’s health. According to the American Lung Association, long-term exposure to air pollutants such as particulate matter, which also can be produced from diesel exhaust, increases the risk of developing respiratory diseases such as asthma and reduced lung, heart, and brain growth.

To avoid environmental degradation and to improve the living quality of future generations, advocates and politicians are urgently seeking solutions. In 2022, New York State passed legislation that would mandate all school buses be switched to zero-emission vehicles by 2035, and all bus fleets that are sold in the state be zero-emission by 2027. The goal aligns with New York State’s Climate Act, which seeks to reduce the state’s greenhouse gas emissions 80% by 2050.

While school districts, bus companies, and contractors are slowly adapting to the transition and putting the law into action, many organizations are offering support. The president of the New York League of Conservation Voters, Julie Tighe, believes the organization needs to help “children who are just trying to go to school where they can learn, and it’s often hard if we send them to school in a vehicle that’s making them sick.”

As the CEO of NYC School Bus Umbrella Services (NYCSBUS), a nonprofit that operates about 850 school bus routes throughout the five boroughs in the city, Matt Berlin feels that passing the bill is not enough, and it is urgent to implement the state’s mandate. In late 2022, his company partnered with NYLCV, WRI, Bronx Community College, CALSTAR, and the Mobility House to launch the project “Electrifying School Buses in Bronx and Beyond,” which received $8 million in funds from New York State Energy Research Development Authority (NYSERDA). The project serves as a case study for other school districts and bus contractors, and the investment will be distributed in the purchase of electric school buses, the laying out of charging infrastructure, and training mechanics and workers in the Zerega depot in the Bronx to adapt to electric school buses.

School buse fleets in NYCSBUS. Photo by Ruonan Jiang.

“The area around this particular depot is at 98 percentile of air pollution, which means it’s very very high,” Tighe adds. “We wanna show it can be done in a very dense urban neighborhood in a way that is beneficial not just for kids who are riding the school bus, but also for the neighborhood around it.”

Working class neighborhoods in the Bronx are exposed to disproportionately high levels of air pollution. According to the New York City Health Department’s Epi Data Report, children in the Bronx have been experiencing high rates of asthma-related medical visits and hospitalizations for years compared to other boroughs in the city. The transition to electric school buses in the Bronx aims to reduce air pollution that is largely caused by heavy-duty traffic and decrease the risk of health concerns for children.

Further research shows air pollution is also associated with high rates of premature deaths, heart disease, and even psychiatric issues. Trevor Summerfield, the advocacy director for the American Lung Association in NY and Vermont, wishes more health organizations such as the Cancer Society and Heart Association could engage in the argument and draw the public’s attention. “We have to take other health people to the table to make sure other people know that it’s not just us that are concerned with this issue, that is the whole [health] community,” Summerfield says.

Implementation of the law will be challenging. Installation of charging infrastructure and the cost of electric vehicles are two main concerns, and Berlin says he is prepared to address them. “Even if there are challenges and costs for the future, it’s better to know them upfront,” he says.

To ensure that electric school bus fleets operate smoothly, more charging stations have to be built, which takes time and costs money. NYCSBUS is working with the Mobility House to use the software “ChargePilot” to manage electricity and establish data connections between charging stations. They have received approval from ConEd to optimize energy usage and avoid overstressing the grid. Furthermore, Joint Utilities of New York, which comprises Central Hudson Gas & Electric Corporation, NYSEG, ConEdison, and three other utility companies, offers “incentives of up to 90% of utility-side infrastructure costs” that school bus companies can apply to.

Regarding the cost of electric buses, Tighe believes educating people about the available funds and support is important. For example, there are different options for transmitting a diesel power bus to electric vehicles, and retrofitting buses may be less expensive than purchasing new ones. Different grants from the state and the federal level are provided for school districts and bus contractors. New York State announced $100 million in funds to help achieve the mandate of electrifying all school buses, and the first-round application was opened on Nov. 29.

Changing to electric school buses is a difficult and long process, but there are many ways to approach it. “People are a little uncomfortable because they aren’t familiar with it, but that’s part of being human, and we’re moving in the right direction,” Summerfield says.

Summerfield hopes knowing that electric school buses can be feasible and durable will alleviate concerns over this transition. “Did you ever take a school bus as a kid? You remembered that smell, like the seats, the diesel. That wasn’t there, and it was amazing.” He remembered driving an electric school bus once in Albany, “and they were so quiet.” According to a bus driver in NYCSBUS, it usually takes two to eight hours to charge a school bus, depending on the capacity of the charger, and a fully charged electric school bus can run more than 100 miles. Based on WRI’s “Electric school bus U.S. market study” in 2022, electric school buses can run up to 210 miles depending on different manufacturers and companies.

Since electric school buses are purchased by some school districts and bus contractors separately, there is no current data about the exact number of electric buses that are already in operation around the state. NYCSBUS now has three electric school buses in the Zerega depot, 25 on order and waiting for delivery, with more to come. “Just this week we’ve been laying out our depots and showing that we’re gonna need 33-40% more space because of charges. That presents a number of challenges,” Berlin says. He is also concerned that almost two thirds of their school bus routes may need midday charging. “It’s not a reason not to drive; it’s not a reason to slow down. But it’s important to know ahead of 2035 so we can plan for it.”

Electric School Bus in NYCSBUS. Photo by Ruonan Jiang.

While advocates, school bus operators, and politicians are inching their way toward the future where all school buses can be zero-emission, Tighe believes newfound urgency is needed. “Clean air is not a partisan issue. Everyone wants to breathe clean air; they want their kids to breathe healthy air. They don’t want their kids to be sick because of the bad air quality coming from the school bus as they are just trying to learn.”

Now O’Brien is an activist and a member of the New York City School Bus Coalition, which was started by NYLCV and some other environmental organizations to advocate for electric school buses. She also works as a Policy and Partnerships Manager in Empire Clean City (ECC), a non-profit organization that is committed to advancing cleaner air and energy. “As a parent, it was just a clear connection with my children and their future,” she says. “In the next two years, we’re supposed to have, I believe, 75 school buses, and we don’t yet. So the NYC School Bus Coalition is trying to keep this issue at the forefront so that we can remind elected officials of these promises and try to support the implementation.”

Asthma Alley – Deepening Data Collection

By Laya Hartman

In early December, La Peña, a local environmental justice group, organized a craft fair in the office space of South Bronx Unite, an organization which fights for Environmental Justice in the Bronx neighborhood of Mott Haven. The women of La Peña had much to discuss beyond the clothing, jewelry, and pottery they made.

Craft sale at South Bronx Unite. Photo by Laya Hartman.

Esperanza Martell, a Puerto Rican craftswoman and environmental justice advocate, spoke of what she called discriminatory infrastructure in the Bronx since she came to the United States at five years-old. Martell, now older, is experiencing severe asthma.

“It’s not that people in the Bronx are not conscious of the environmental issue of the level of pollution, you know, which didn’t start four years ago,” said Martell.

But for Martell, New York is her home. La Peña and South Bronx Unite fight for Bronx residents to live safe and healthy lives– but structural issues in the Bronx make this a steep challenge.

The Bronx absorbs much of the city’s pollution, and this was no design flaw. In the South Bronx are four Peaker Plants, waste management plants (handling a third of New York City’s waste) a water front made inaccessible by factories, and four major highways: the Major Deegan, Bruckner, Sheridan, and the Cross Bronx expressways which run directly next to homes and playgrounds. The pollution from these cars and diesel trucks contribute to the poor air quality that gives locals severe asthma. All of these major infrastructures still exist today.

View from Third Avenue Bridge to Willis Avenue Bridge. Photo by Laya Hartman.

As a result of red-lining in the early to mid 20th century, many Black and Hispanic residents were forced to live in areas with structural dangers. This is seen today as the South Bronx reports the highest levels of toxic emission in all of New York City, and is majority Black and Hispanic.

Professor Neal Phillips at Bronx Community College has done extensive work with air quality and pollution in the United States. Phillips believes that the Bronx needs a lot more air quality research and public knowledge of these issues. “I think the government needs to make more funding available so people can do more research and develop low cost sensors for air quality indoor and outdoor air quality,” Phillips said. “If I can buy one for $10, I could put it in my home, every bedroom.”

The goal is for citizens to be able to monitor their own areas of living. If air quality is poor in a specific area one day, then that person should try to avoid that area.

Retired Professor Angelika Winner at Lehman College in the Bronx believes that working with the communities that are affected and know the areas well is essential to solving environmental issues. “Scientists need to do a lot better in making their research more accessible, but also from the ground up, to not just remain in your ivory tower, but actually work with the community,” said Winner.

Air quality devices can be very expensive. Winner believes that the lack of research sites could be a result of officials not wanting to invest money to fix these issues. “It’s better not to know in some ways for the officials,” said Winner. A mix of monetary expenses, and giving away individual freedom are several factors Winner believes could hold officials back from more research and taking necessary steps to solve the problems found.

For example, on a day when high ozone values are found in a city, Winner believes all private traffic must be stopped in particular areas. “I think in the US there’s a constant clash between individual freedom. Like you can’t take my right away to drive into the city,” said Winner. Communities working as a collective, where actions have a positive effect on the next person, could help mitigate poorer air quality and other environmental issues.

Groups like South Bronx Unite work to connect air quality research with policy and solutions. Leslie Vasquez, an activist working for South Bronx Unite, spoke on how green spaces in the South Bronx are underutilized. “It’s a tricky situation when you want to advocate for something And it just doesn’t happen because of the lack of funding that these programs have,” said Vasquez.

St Mary’s Park, one of the largest parks in the South Bronx, lies in Mott Haven. According to Mark Naison, a researcher at Fordham University, the park has three needle boxes where heroin and methadone users can discard their works. The existing green spaces are not always child-friendly.

Community activist Nieves Ayress is a former political prisoner of the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinoche in Chile. Ayress, speaking little English, had a translator paraphrase her disapproval of the United States Government’s efforts to address many environmental issues in the South Bronx. “Whatever pieces of goodness that you find in the Bronx, don’t think it’s because the authorities are good…It is because the community has been working together,” said Ayress.

Nieves Ayress stringing jewelry at Craft Sale. Photo by Laya Hartman.

Martell agrees with Ayress in their disapproval of the city’s efforts to re-invision spaces in the South Bronx. “I mean, they [the Government] always blame the victim. It’s always the people’s fault. But the people organize themselves.”

Le Peña brings awareness to these issues in the community. To Martell, the changes that have been made in the Bronx have been pushed by the people to fight resistance from the government’s lack of urgency and funding. “We gotta fight back, and we fight back,” said Martell. Where waste plants and factories exist, La Peña would like to see community gardens, parks, and child-safe playgrounds.

Efforts that have been made by La Peña to help solve these issues have included painting murals around the South Bronx. Several members of La Peña added to the creation of these murals. The most recent mural painted in 2023.

But optimism remains in the minds of many researchers and citizens. Fighting for environmental justice is not an impossible mission, with the help of community organizations, working with scientists and researchers to raise awareness and advocate for change in their communities. “You start somewhere and make things more available to the regular people, then that’s a step in the right direction,” said Phillips.