Solar in the City

By Susanna Calhoun

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit in 2020, Georges Piette, originally from France, decided to upgrade both his home and yoga studio in Park Slope by adding solar panels on the roofs. For Piette, the city tax incentives and his Buddhist beliefs made the pricey investment worth it.

“In Buddhism, you don’t want to do harm,” said Piette. “We say harm to any sentient being. But sentient being doesn’t mean just human. It means the animals, it means everything alive on the planet. So it’s our job to do good for them and stop the harm.”

Piette’s yoga studio, Yogi and Yoginis. Image by Susanna Calhoun.

Piette worked with Brooklyn SolarWorks, a solar design and installation company, to install a canopy on his studio’s roof with 30 solar panels. The solar panels power all of the studio’s daily electric usage.

Due to fire code, city roofs must maintain a six-foot clearance from the front to the back of a building. Brooklyn SolarWorks invented a specific canopy design that raises the solar panels nine feet off the ground to allow firefighters access underneath.

Solar panels elevated nine feet above roof. Image by Susanna Calhoun.

While installing solar panels in the city may be more complicated than in more rural areas due to flat roofs, shading from skyscrapers, and complex permitting issues, the benefit to New York City residents may outweigh the hassle. Homeowners who install solar panels can on average save $2,000 to $5,000 dollars annually and business owners can save $5,000 to $15,000 annually, according to Brooklyn SolarWorks. Those who install panels can expect to see a return on their initial investment within four to six years.

Approximately two-thirds of New York City’s carbon emissions come from the estimated one million buildings spanning across the five boroughs. “They just emit so much CO2 into the environment. They’re bigger polluters than like cars themselves, especially in such a dense environment like New York City,” said Daisy Rivera, a solar specialist with the NYC Accelerator.

Rivera, from New Jersey, was concerned about how fossil fuels affect her health since she suffers from allergies. One day Rivera received a newsletter about a new power plant being built in one of her neighboring counties. “I was so upset. I was like what else can New York do to us and just keep dumping on Jersey,” she said. When Rivera learned of solar energy, she was intrigued.

Rivera finished her graduate degree in environmental policy in 2020 from Pace University. In 2022, Rivera joined the NYC Accelerator as a solar specialist. “I knew I needed to pursue and go down this failed industry,” she said. The NYC Accelerator helps building owners find resources and provides support to improve energy efficiency and reduce carbon emissions.

Solar energy flow is created when photons from the sun are absorbed into the cells of the solar panel, creating an electrical reaction. A classic silicon solar panel is 76% glass and made up of other materials such as polymer, aluminum, copper, silver and metal. On a sunny day, homeowners can reap the clean energy benefits from the solar energy they create. If they create excess energy, the excess will feed back into the grid and their utility company will reward them with credits, saving money on their electricity bill.

For the average home in New York City, solar panel implementation, including design, equipment, installation, permitting, and warranties, begins at around $30,000 before any added tax incentives, according to Brooklyn SolarWorks. “If you’re poor, you’re not going to do it,” Piette said.

But for those interested and able, some residential solar projects can be covered 70% or more with added tax incentives and rebates. “There’s such great tax incentives to go solar right now. And there’s such a greater importance that we have to switch off of fossil fuels and onto cleaner energy sources,” said Ryan O’Hara, a business development manager at Brooklyn SolarWorks. Homeowners can take advantage of several tax credits, including the New York State solar income tax credit, the New York City Solar property tax abatement, and the federal solar tax credit.

The tax incentives available to New York City residents and business owners differ. “A commercial building like this [yoga studio] is an investment building. So there’s less help,” said Piette. But Piette believes he’s already broken even on his home. “My bill at my house is $16 a month. Okay, that’s what I pay. I have three floors. $16 a month, which means it’s the minimum that you need to have an account, right?” he said. The average electric bill for residents in New York City is $193 dollars a month, according to Energy Sage.

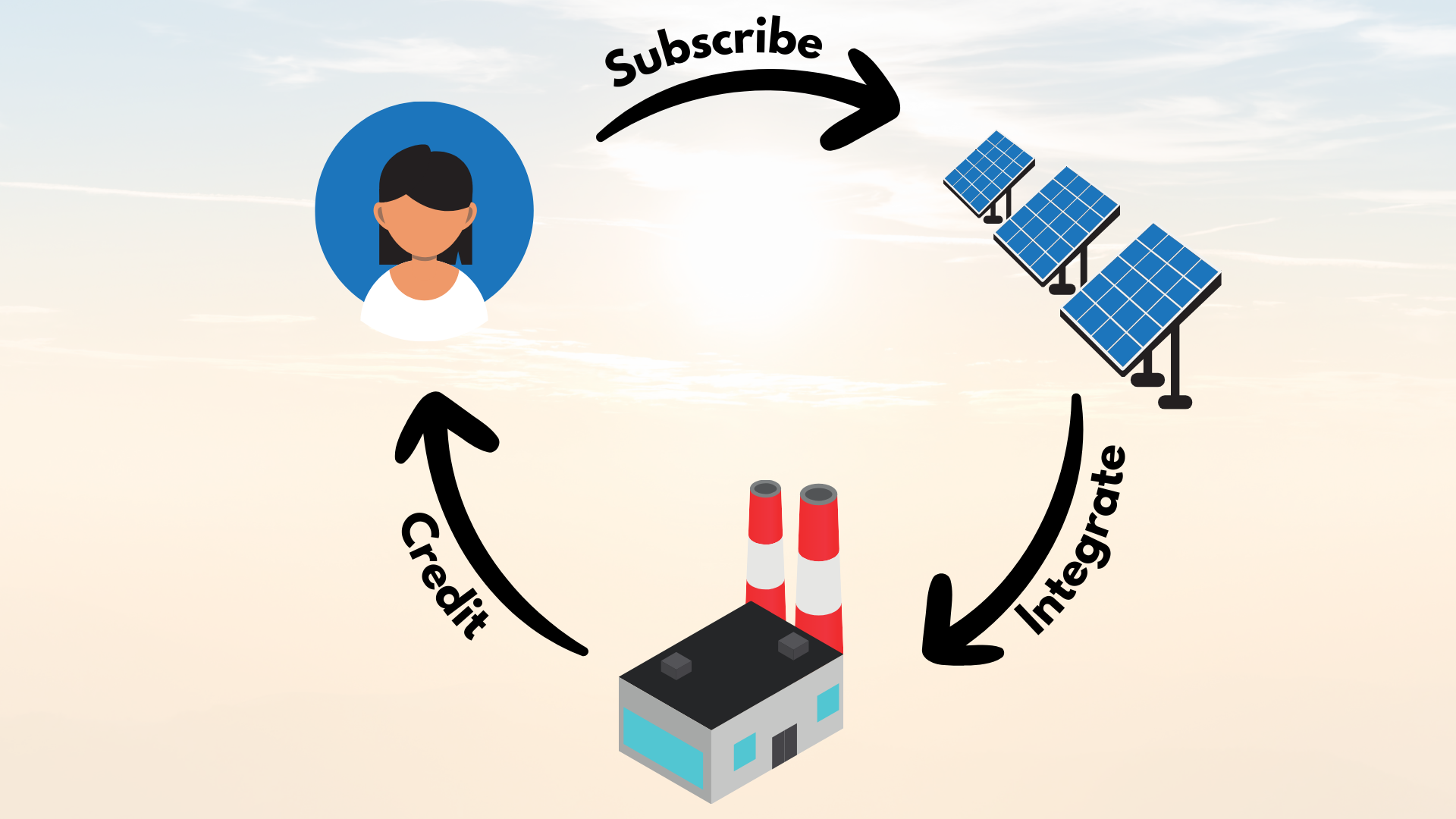

But what about the majority of New Yorkers who rent, don’t have the roof space, or cannot afford to install solar? Community solar is an innovative approach where people can subscribe to the benefits of solar without the actual installation.

Community solar can be installed on farms, parking lots, warehouses, housing developments, and public buildings. Those who subscribe to community solar receive credits that offset a portion of their electricity bill. Subscribers contribute to the generation of clean energy equivalent to their subscription package, though the energy they receive is not directly derived from the energy being produced and is mixed into the grid.

Community solar explained. Image by Susanna Calhoun.

Kaila Wilson, the director of Energy Development at the RETI Center, is working on a community solar project on the New York City public housing authority. “We are mostly trying to sign up people, so get particularly low and middle-income subscribers signed up so that they can get the benefits,” she said. Community solar allows renters, low-income, and those in black and brown communities who have often been subjected to large peaker plants in their areas, to partake in the energy space and reduce electricity bills.

Gowanus Gas Turbines Station and Joseph Seymour Station in Sunset Park. Image by Susanna Calhoun.

With rising concerns about climate change and carbon emissions, the New York City Council has set a goal to install 1,000 megawatts of solar panels by 2025, and in 2019 the city introduced the Climate Mobilization Act which included local laws 92 and 94. The laws aim to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 40% by 2030. The laws require that all new constructions or renovations incorporate solar panels or green roofs.

“There is a lot of pressure for people to take responsibility, people, meaning governments to take responsibility of their carbon footprint and to be held accountable for what they’re doing to the planet,” said Abby Kaufman, an account supervisor at Antenna Group, a marketing and communications company focused on helping sustainable and mission-driven companies innovate.

Also introduced as a part of the act, and what the Adams administration calls a “nation-leading emissions law,” Local Law 97 requires most buildings more than 25,000 square feet to reduce greenhouse gases and meet new energy efficiency limits by 2024. On September 12, 2023, the Adams administration introduced “Getting 97 Done,” a new strategic plan to support local law 97 goals. The administration hopes for the city to be carbon neutral by 2050.

But what’s the draw to solar for New York City over other renewable energy sources? Solar is a flexible technology, its advocates argue. “You can’t put wind turbines on rooftops of a big warehouse in an urban area,” said Sam Ditesheim, a solar product developer at DSD Renewables. O’Hara believes solar will be the leading energy source in the next couple of decades. “People are realizing that this technology is super useful, super effective and super cheap. At the end of the day, it’s leading to a lot cheaper electricity prices throughout the world,” said O’Hara.

The city is currently behind on its goal to reach 1,000 megawatts of solar by 2030 and hopes to catch up. For those looking for a long-term cost-effective solution to their energy bills and those wanting to do their part in reducing carbon emissions, solar is a compelling option. “I think the big promise of solar is just like, you’re doing things for yourself and for the greater good,” said Kaufman. “Like, whether it’s money, the climate, the greater power system, meeting state goals, federal goals…you’re a key piece of the puzzle.”

Guard a Touch of Green in Mott Haven

By Qingyue Zheng

On a Saturday afternoon in December, in front of Maria Sola Garden in Mott Haven, Aresh Javadi was dismantling wooden bench parts from his truck. These benches were donated by a nearby restaurant, which Javadi had acquired in so the garden could have more places for people to rest.

As an artist, Javadi was always glad to decorate this garden bit by bit. In his hometown, Iran’s Shiraz, there were many gardens; the design of different geometric shapes inside the garden added a sense of holiness. But the South Bronx offers a different scene. “ Creating green spaces that will give back energy both to the people and the people give back energy to the trees, especially this neighborhood has been least given monies, funding, and support for the wellness of the people,” Javadi said.

Javadi and Charlie dismantle wooden chairs donated by local restaurant. Photo by Qingyue Zheng.

Working with him is Charlie Johnson, who is also one of the volunteers at the garden behind them. “I don’t have a backyard, so this is my backyard where I bring my family every day, and we have our access to nature,” Johnson said.

Although the Maria Sola Garden is small, it is an irreplaceable presence in the neighborhood of Mott Haven, which is filled with truck exhaust and lacks green space. The Bruckner Expressway bounds the neighborhood to the east, and the Deegan Expressway lies to the south. Thousands of trucks pass through the area daily, emitting harmful fumes. Despite Mott Haven being near the Harlem River, the vast waste management station that handles the all Bronx’s trash separates residents from the river, and the wind blows unpleasant odors into the neighborhood.

Highway in Mott Haven. Photo by Qingyue Zheng.

Mary’s Garden is the only real green space in the Mott Haven section of the South Bronx. “My parents informed me at an early age that’s not coincidental. That was intentionally designed. We lack green spaces compared to most parts of the city, and that has direct correlations and connections to the poor,” said Matthew Shore.

Born in the Bronx, Shore experienced a deep sense of environmental injustice at an early age. To try to make change, after completing a master’s degree in urban planning at Columbia University, he returned to Mott Haven and worked at an organization advocating for green space equity. His office is diagonally across from the garden.

Faced with limited green space, residents began to create their own. The tale of Maria Sola Garden began 13 years ago when Jose, the original owner, named the garden after his wife. After his death, volunteers adopted the garden and began to maintain it for free. Behind the garden is the Deegan Expressway, and car exhaust has made the soil unsuitable for growing fruits and vegetables. Thus, flowers and plants are in the garden. “Everything is basically donated, and everything is from volunteers. Everyone brings something they’re good at and tries to contribute to the Garden,” Johnson said.

Residents arrange donated books in the garden. Photo by Qingyue Zheng.

George Axiotakis is the gardener and comes to the garden at least three times a week. When the garden fences are full of flowers in spring, locals will come to take pictures. That is when Axiotakis is most proud. He also created a pond for the garden, where more than 20 goldfish lurk under the lotus leaves.

The garden is a living room and backyard for the neighborhood residents, and when there is a lively community event, it is the time for DJ Jose to shine. “I meet people, know what they like, play what they like. And they don’t even know,” Jose Echevarria said triumphantly.

The reasons why volunteers give their time and love to the garden are similar. The residents here desperately need green space.

“My wife got asthma from living here as many asthma attacks since we’ve been here. My son has a problem with his lungs too,” Johnson said. His wife Karla Rodriguez sat down with their son on a bench in front of the Garden. “Like some mornings, you’ll have a long line on these streets of just trucks um and all that exhaust and all that pollution into the air. So that’s what eventually led to me having asthma,” Rodriguez said. She has had five asthma relapses here. Echevarria’s friend had a similar problem. “They didn’t get too far. They’re asthmatic now; you see them with oxygen tanks, ” Echevarria said.

Asthma is a part of life for residents living there; the neighborhood where the garden is located has the nickname ‘Asthma Alley’. According to 2019 reporting from the Guardian, Asthma-related hospitalizations from Mott Haven are five times higher than the national average and 21 times higher than in wealthier New York City neighborhoods. “When you look at all of the 11 public hospitals in New York City, the one public hospital we have here in our neighborhood of Mott Haven, Lincoln Hospital, ranks number one — unfortunately, for asthma hospitalizations,” Shore said.

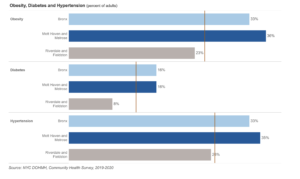

The amount of green space is closely linked to people’s health. According to New York City’s environmental and health data, the affluent Riverdale neighborhood in the Bronx ranks first among the city’s 59 community districts in available trees. Mott Haven ranks near the bottom. New York State Department of Health data shows that Mott Haven children are three times more likely to suffer from asthma than Riverdale. In addition, Mott Haven performed worse than Riverdale in several health statistics, including obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and pedestrian injury hospitalizations.

Statistics by NYC DOHMH, Community Health Survey, 2019-2020.

The nearby waterfront is no more helpful for the residents of Mott Haven. The NYC Comprehensive Waterfront Plan, a report released by the city last year, notes that fewer than half of Bronxites who live within a half-mile of a waterfront have safe pedestrian access to those coastal stretches, compared with 90 percent of Manhattanites.

To increase Mott Haven’s green space, South Bronx Unite, a grassroots organization in South Bronx, has proposed the Mott Haven – Port Morris Waterfront Plan, which aims to make the waterfront at the end of the neighborhood accessible to more residents. The goal is to offset potential harm from air pollution and combat climate change. Shore joined the organization this year, advocating for this project.

Every time Shore walked on the waterfront, he saw the beautiful scenery but had mixed feelings. Opposite the flowing seawater and the intoxicating sunset was the vast waste management station. The railway line for transporting garbage separated people from the river, and the trucks constantly came and went, making it very dangerous for people to enjoy the sea breeze even if they wanted to. In 1991, the New York State Department of Transportation leased the valuable land to Harlem River Yard Ventures. It subleased it to many fossil fuel-intensive businesses, from last-mile warehouses to peak power plants to waste transfer facilities.

“The function of this waterfront is to do anything but serve the community. Many people don’t know that this exists because there’s no like sidewalks that will direct and provide you with any indication that there is anything over here for you to enjoy,” Shore said.

Matthew looks at the waterfront. Photo by Qingyue Zheng.

At sunset, Shore walked to the Harlem River; he could see Randalls Island, where the parkland-filled areas are. He looked down and saw that near the shore, a flock of geese were playing, “The geese, they have the right idea. They have a nice spot, but we don’t.”