Gowanus Rezoning

Done Deal or Pipe Dream?

By Lyuwei Chen

Wearing a bikini, swimming goggles on her head, and a towel on her shoulders, Nora Almeida stood at the entrance of the chilly 4th Avenue subway station in Brooklyn, where there is no beach, only hurrying pedestrians.

Although it was a late autumn morning, there were also a few other people in swimsuits, holding swimming rings and yelling “our houses are flooded and we are swimming in our basements.” Others were wearing suits and holding umbrellas. “Look at the empty land over there, it’s big enough to build more buildings,” they cried out.

Members of Voice of Gowanus protest against the Gowanus Rezoning.

They are residents of Gowanus and they hoped they could stop a massive rezoning proposal in their Brooklyn neighborhood. These activists in particular call themselves Voice of Gowanus, a coalition of neighborhood associations recognized as one of the most outspoken opponents of the 82-block rezoning proposal that would build 8,200 new affordable apartments on top of toxic chemicals that have been in the soil for more than a century. The rezoning would introduce roughly 20,000 new residents to the neighborhood by 2035.

“I am not cold, I am very angry now,” said Almeida, trembling in the wind. Having spent many days dealing with the damage caused by Hurricane Ida, she said she has gained a deeper understanding of how climate change is impacting the lives of locals.

The industrial neighborhood is going to change into a huge residential area.

Historically, Gowanus has suffered from floods and was marked as “Flood Zone A” by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). In 2012, when Hurricane Sandy hit Gowanus, the toxic water in the Gowanus Canal, an EPA Superfund site, overflowed and flooded the neighborhood nearby.

In 2021, because of Hurricane Ida and sewage flow problems caused by old infrastructure, Gowanus encountered flooding again. “My basement has been flooded many times since I bought [my house],” said Linda La Violette, the co-chair of Voice of Gowanus.

Despite how controversial the Gowanus Neighborhood Rezoning is, on Nov. 23rd, 2021, the City Council approved the controversial Gowanus Neighborhood Rezoning by a vote of 47-1. Gowanus will transform from an industrial neighborhood into a huge residential area of towers and shopping centers roughly double the size of Hudson Yards, a massive development on Manhattan’s West Side.

Council members Brad Lander and Stephen Levin at City Hall.

“It is an important moment to stop and look at what is broken in our reactive land use process in the era of climate crisis, of affordability crisis, [and] of aging infrastructure. We need a more strategic and more proactive process that grounds future planning in the shared values of New Yorkers,” said Brad Lander, a New York City Council member who championed the Gowanus Neighborhood Rezoning, during the final vote in City Hall.

Lander also mentioned that the de Blasio administration has agreed to invest $174 million to address flooding specifically on 4th Avenue, one of the sites where flooding has occurred in recent years. Projects funded by this money will include rebuilding the 19th street pumping stations and adding new infrastructure along 3rd and 4th Avenues, with the intent of addressing flooding issues in the future.

However, Voice of Gowanus argues that instead of effectively addressing the flood problem in Gowanus, the rezoning plan will create more environmental issues. Most of the new public housing, the Gowanus Green Program for low-income families, will be built on top of the expanding toxic floodplain, the former location of the a Manufactured Gas Plant.

The new public housing, the Gowanus Green, will be built on top of the former location of the a Manufactured Gas Plant.

“We are not going to let them put vulnerable people at risk…we will take the city to court,” said LaViolette. In order to stop the rezoning, Voice of Gowanus has retained attorney Richard J. Lippes, who has argued environmental cases in 20 states — including the well-known Love Canal case.

The battle over the industrial neighborhood’s future and the fate of the Gowanus waterfront is hardly unique. New York City’s 520 miles of waterfront, more than that of Miami, Boston, Los Angeles, and San Francisco combined, has been an industrial and shipping hub for centuries.

New York City has been rezoning its waterfronts since 1993, when it adopted special zoning regulations affecting waterfront development. Intent on maximizing the public’s access to, and enjoyment of, the city’s waterfront resources, this plan also has fulfilled developers’ decades-long desire for high density, mixed-use areas along the shoreline of New York City.

However, global warming causes sea level rise and, consequently, has increased the intensity, frequency, and duration of coastal flooding in New York City. According to the NPCC climate change projections, by the end of the century, New York City may face an increase in mean annual temperature of 4–7.5 Fahrenheit, an increase in the base level rainfall of 5–10%, and a rise in sea level of at least 12–23 inches.

Although the EPA has cleaned up the Gowanus Canal, coal tar, garbages, and leaves can also be seen on the water.

“As sea level rises, coastal flooding will happen in the future with greater frequency and severity because smaller hurricanes will result in tides which are the same height of those created by bigger storms at lower sea levels, as for instance, Hurricane Sandy did in 2012,” said Dr. Klaus H. Jacob, an earthquake, disaster, and climate scientist at Columbia University’s Earth Institute.

Additionally, Jacob mentioned that nor’easters, extra tropical storms that form along the East Coast of North America during winter months, produce heavy snow and blizzards, rain, and coastal storm surges and lead frequently to widespread coastal flooding.

Estimates from the Flood Risk Overview of Gowanus demonstrate that there are 111 properties in Gowanus which, based on the calculation of current density, have a greater than 26% chance of being severely affected by flooding over the next 30 years.

More than 50 artists from Arts Gowanus and Brooklyn Art Cluster suffered the effects of the flooding caused by Hurricane Ida on Sep. 1st, 2021. Sewage water ruined many of their finished pieces of art, works-in-progress, and raw materials. “It was a disaster,” said Johnny Thornton, Executive Director of Arts Gowanus. “Sewage water flowed everywhere. It was so disgusting.”

Jo-Ann Acey, an artist at Arts Gowanus, estimated that she lost $70,000 in finished artwork. “When I saw my framed paintings soaked in the water, I hate to admit, I cried.”

“Most individual artists have no insurance to cover their losses,” said Keun Young Park, the co-founder of Arts Gowanus and the Brooklyn Art Cluster. In hopes of easing Acey’s situation, she published Acey’s story on the crowdfunding website GoFundMe, resulting in $70,000 in donations, which helped Acey get through the difficulties.

On Oct. 3rd, 2021, Brooklyn-based artists facilitated a community Yarn Bomb project on 4th Ave in Gowanus, using art to celebrate the climate resilience of the neighborhood. They named their work “CODE RED!” to highlight the Climate Change Emergency impacting New York City.

In addition to worrying about flooding caused by climate change, community groups on the waterfronts are also fearful of over-gentrification and the resulting displacement of working-class tenants. Rezonings of all kinds, across the city, have faced intense opposition.

The tug-of-war surrounding the transformation of the Gowanus neighborhood is not new, either. “The houses in Gowanus are affordable now. I don’t understand why they want to build more affordable housing which will displace most artists and small businesses in this location,” said Martin Bisi, who runs a music recording studio in the old American Can Factory on 232 3rd Street, a block away from the Gowanus Canal.

Bisi used to hope that he would be able to keep this studio, which he has rented since 1979. However, his dream has been crushed by the reality that a tower will be built on top of his studio. Facing the result of the final vote, he said disappointingly, “I expected it [might pass]. But I didn’t expect it to be 47-1.”

Katia Kelly, member of Voice of Gowanus.

Katia Kelly of Voice of Gowanus lives 2.5 blocks away from the Gowanus Canal. An immigrant from Germany, she and her family have lived in the neighborhood for 36 years. Having tried to remediate the toxic legacy of the Gowanus Canal since 2006, Kelly said that the potential health risks associated with the toxic Gowanus Canal flooding have been bothering her.

“No one [in the government] is hearing our voice,” Kelly said. Now that the Gowanus rezoning is truly about to proceed, in addition to her usual worries, she is also confused. “We don’t understand. The canal is so polluted. Why would you go ahead but not clean it up first?”

Under Water

The Mitigation Reconstruction of the Hugh L. Carey Tunnel

By Ziru Wang

On the night of Oct. 22nd, 2017, the Hugh L. Carey Tunnel were shut down for the installation of new floodgates.

The gates, each weighing 15,000 pounds, were lifted by an enormous crane at the entrance of the tunnel. Surrounded by inspectors, installers, supervisors, and workers, two design and fabrication companies removed the base plates in the road, sucked the water out with a ventilation truck, gently swung the door closed, and tightened those last bolts.

The installation of the floodgate. Oct 2017. by Walt and Krenzer, Inc.

During Hurricane Sandy, the storm surge came into lower Manhattan, right up to West Street and then across Morris Street into the tunnel plaza, eventually filling the whole tunnel with water.

After continuously pumping for two weeks to get the water out, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority needed to repair the walls, electrical systems, lighting, and communication systems that was eroded and soaked through by contaminated saltwater.

There was no flood mitigation in the tunnel before Hurricane Sandy. Opened in 1950, the Hugh L. Carey tunnel underwent a significant reconstruction in the 1990s. Back then, engineers and scientists had not considered the factor of climate change. They put in a new roadbed, updated the ventilation and replaced the old tiles.

The ventilation in Governors Island, built upon the lowest point of the Hugh L. Carey Tunnel.

There were no mitigation tools or flood barriers to block the water out, even right before Sandy. Therefore, the water effortlessly rushed into the tunnel and caused devastating damage.

“I think there was an understanding that the tunnels could flood, but it was not taken as seriously as it might,” said John Hinge, the assistant engineer of MTA Bridges and Tunnels. “Hurricane Sandy was the wake-up call.”

In 2013, the MTA hired Hinge after Sandy hit New York City. From then on, he was involved in many actions such as assessing damages, creating preliminary designs, and looking at multiple potential mitigation measures with different agencies and companies.

With the $403 million from FEMA, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the MTA was able to build mitigation tools in both Queens Midtown Tunnel and the Hugh L. Carey Tunnel.

John Hinge, standing inside the office of MTA Bridges and Tunnels.

They built a reinforced concrete wall along the road near the entrance, created stop logs that were the first defense of the water on the road, and evaluated different contracting mechanisms, coming up with the floodgate at the end.

“It has the lowest cost, least deployment effort, and it is the longest-lasting solution,” Hinge said.

The process of creating floodgates for the Hugh L. Carey tunnel was unique. According to Katie Montague, the assigned project engineer of the floodgate from Walt and Krenzer, Inc., it took her four months to finish the design, compared to a two or three-day workload for a normal floodgate.

There were two significant challenges to tackle. Being at the bottom of a slope, the entrance of the tunnel needs to be cleared and reshaped to swing the door open, and this complicates the ceiling around the bottom and the sides, and particularly between the two panels.

Hugh L. Carey Tunnel. The tunnel connects two boroughs rich in diversity.

Also, to maintain the aesthetics and simplify the mechanism and operation as much as possible, Montague redesigned the compression mechanism to use the possible pressure of the floodwater to make the gate effective while the water is creeping up.

Instead of going against water, the process would “rely on water,” Montague said.

Before the official installation, Montague and Ben Rising, the president of Walt and Krenzer, tested the tunnel. They put the gate into a 26-ince deep steel box filled with water and pressurized the gate to the complete design pressure for an hour. As a result, the leakage was only 1/100th of the allowed volume.

“It performed just as we expected,” Rising said.

Rising used to design ships, including military ships and commercial ships. Since 1993, Rising has worked at Walt and Krenzer and started designing floodgates and flood barriers.

As an engineer who witnessed the changes in demand regarding flooding mitigation systems, Rising sees Hurricane Sandy as a turning point. “Probably 60% to 70% of the work that we have done has been a response to Hurricane Sandy.”

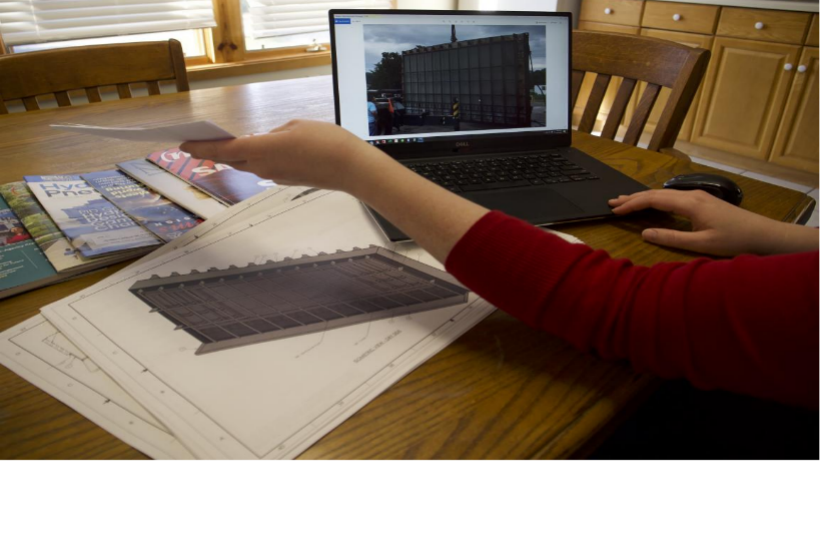

Katie Montague sits in front of the table, comparing the picture with the printed 3D model of the floodgate.

On Nov. 15, 2021, President Joe Biden signed a $1 trillion bipartisan infrastructure bill. With the money, many new projects might be possible. As for New York City, 80 percent is directed to highways and road projects and much of the rest to public transit. How much will be spent on mitigation and flood resiliency remains to be seen.

The concern of climate change continues in the post-Sandy era. Even if Sandy was almost a decade ago, its impact on the city is still felt in many ways. Elevated housing, multiple floodgates for buildings, piles standing on the sea, and new construction are all climate matters.

Emily Thompson, the general counsel at the Governor’s Office of Storm Recovery, personally spoke to many family members who lost someone during Sandy. “Houses can be rebuilt, but family heirlooms and your memories cannot be replaced.”

The possible benefit-cost ratio of climate mitigation is anywhere from 4:1 to 13:1, according to Klaus Jacob, the geophysicist at Columbia University who forecast that Hurricane Sandy would come before 2012.

“It’s progressive in Wall Street. But here, in climate change, nobody wants to spend the money,” Klaus Jacob said.

As a scientist concerned with seismic and hydro-geochemistry, Klaus worked in the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory that collected climate data nearby. Since building a new house in Piermont in New York State with his wife Elizabeth, he has become an experiential fieldworker who lives in a projected flood zone.

During Sandy, Klaus’s house was flooded on the first floor. Two cars of his were washed away. At the same time, they were forced to repair the waterlogged floorboard and the fridge.

After that, Klaus tried to collaborate with other residents, though the response was only from people who lived in the coastal area. It wasn’t until the summer of 2021, when Hurricane Ida hit the higher point of the village with mud flows and extreme rainfall, that those living further from the coastline were more concerned about climate change.

“Once they are affected, they become interested,” Klaus said.

The floodgate in the Brooklyn Side.

The risk of getting impacted by climate change is increasing in all places. In Ben Rising’s neighborhood of Woodbury in New York, a state trooper was swept away by floodwater this year. “In the future, even areas where you don’t have a big river or sort of modest-sized river can become quite dangerous.”

As for the Hugh L. Carey Tunnel, the installation of floodgates would probably still be temporary mitigation to stop the water from getting in, without counting on the possibility that the entrance can someday be underwater.

“Even the measures that we are putting in place now may not be sufficient for those aged 60, 80 years from now; we’ll have to see what happens in terms of sea-level rise,” John Hinge said.

Oysters: New York City’s Unlikely Savior

Battling climate change, one oyster at a time.

By Nicole Guillen

On the banks of the East River waterfront in Domino Park, bundled up in warm water-resistant protective gear, small groups of community scientists, community residents, and educators sat by the water’s edge cradling miniscule mollusks and curious creatures.

Led by the Billion Oyster Project, this oyster research station training teaches individuals how to track oyster growth, identify organisms living among the oysters, and make individuals feel comfortable at the waterfront when working with children.

Billion Oyster Project member Agata Poniatowski leading an oyster research training session.

“There’s just like this thing that goes off, you know, you can see it in their faces. That’s one of my favorite things about working for the Billion Oyster Project is allowing people to really engage with our harbor,” said Agata Poniatowski, the Outreach and Engagement Manager for BOP.

The Billion Oyster Project was founded in 2014, with the goal of restoring one billion oysters in the New York Harbor.

Currently, they’ve planted more than 75 million oysters.

Billion Oyster Project bin of oysters being measured during the training session.

“Oysters are considered a keystone species in the New York Harbor. So, oysters provide a habitat for a lot of organisms, they’ll filter water. But one of the other important reasons we’re putting oysters back is that they provide shoreline stabilization,” said Poniatowski.

Not only have oysters been one of New York’s most popular seafoods for centuries, but they are being used as a unique method of restoring New York’s heavily eroded coastline and combatting the negative effects of climate change.

Oysters from the Domino Park research station in Williamsburg.

Organizations like the Billion Oyster Project are at the forefront of this environmental work and advocacy as they collaborate with public school students, volunteers, community scientists, and restaurants.

The founders of BOP, Murray Fisher and Pete Malinowski, met at the Urban Assembly New York Harbor School, a high school with a focus on maritime studies and environmental work.

“It’s just like a regular high school except not at all,” said Aneal Helms, the assistant principal of Urban Assembly New York Harbor School.

Located on Governors Island, this school provides students with a college and career preparatory education built upon New York City’s nautical experience. They hope to instill in students the ethics of environmental stewardship and skills associated with careers on the water.

“Kids will have their regular algebra, english, social studies, and then all of a sudden they are driving a boat on the Harbor. And then they’ll go back to class,” said Helms.

This school has seven different career and technical education (CTE) programs that students enroll in. Each CTE program deals with a different aspect of oyster farming, ranging from aquaculture research to professional diving.

“What our students are trying to do has never been done before. It’s not like there is a manual to say this is how you restore the New York harbor with oysters. There’s no manual for that. They are making up solutions to this problem,” said Helms.

The New York Harbor School wouldn’t exist how it does today without the Billion Oyster Project. And the Billion Oyster Project wouldn’t exist without the New York Harbor School.

“There’s lots of problems to be solved everywhere. So why not start a school around that problem, you know? And get young kids and their creative and young minds invested and engaged in solving this [climate change] problem,” said Helms.

In recent years, the negative effects of climate change have been palpable as New York attempts to cope in numerous ways.

Coney Island beach and coastline.

For starters, sea level rise is being caused by the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation—what is better known as the gulf stream.

“What’s happening now to the natural system in New York is you have this extreme cold arctic water… going past New York 24 hours a day,” said John Burt, the head of the Environmental Studies Program at NYU Abu Dhabi. “What’s happening with climate change is that circulation is slowing down, so that water is warming up slowly over time.”

Burt stressed that as the oceans warm up, not only will New York encounter sea level rise but increased frequency and strength of storms.

In addition to storm damage, erosion is also caused by the actions of waves, wind and water currents along the shore, and ice. Human activities such as construction, shipping, and dredging also play a roll.

The New York Department of Environmental Conservation has worked with the Billion Oyster Project in the past, funding their Soundview Reefs project, helping expand the BOP’s school-based curriculum, and increasing opportunities for at-risk youth to learn about shoreline and habitat restoration efforts.

Certain areas of the coastline are especially vulnerable to storm damage and erosion due to the impact of waves from adjacent bodies of water. Oyster reefs are being used to soften the blow of these waves and help protect the coastline.

Coney Island coastline.

Oyster reefs are a form of breakwaters, which are urban engineering structures used to combat sea level rise by recreating the function of natural ecosystems.

There are two main methods when it comes to assembling these structures: hard engineering and soft engineering.

Hard engineering consists of building artificial structures to combat coastal erosion.

“Breakwaters that we build today, we call those hard engineering structures, and they are basically doing the same function as what natural ecosystems do,” said Burt.

However, scientists argue that in the long run, hard engineering is unsustainable and more costly. These engineering structures normally cost state governments billions of dollars in maintenance.

On the other hand, soft engineering consists of using natural marine structures such as oyster reefs, mangrove beds, and coral reefs to soften the blow of waves and protect the coast.

One great benefit to using oysters as soft engineering structures are that they are naturally adaptive. This reduces the amount of money and effort needed to maintain the structure overtime as the environment changes.

“If you build an oyster reef and the sea level rises by ten or fifteen centimeters or inches, they will continue to grow up until they are basically exposed to air at low tide,” said Burt.

Currently, the Governor’s Office of Storm Recovery is working closely with SCAPE, a design-driven landscape architecture and urban design studio, to construct a soft engineering based ecological design project known as Living Breakwaters.

This project will be the first of its kind and aims to approach climate risk reduction through physical, ecological, and social resilience along the South Shore of Staten Island.

“What makes this project so unique is the materials that we’re using, the connection to the marine habitat, and how that also interacts with our world and climate,” said Emily Thompson, the Chief External Affairs Officer from Governor’s Office of Storm Recovery.

Having begun construction in August of this year, the assembly of the Living Breakwater has been going swimmingly. The installation of marine mattresses and crushed stones that make up the base layer of the breakwater have been completed, marking the first major milestone for the project.

This breakwater will help alleviate wave impact and storm damage in the Tottenville neighborhood of Staten Island.

“If you look on the map of all waves, they kind of funnel into this one particular area. So, it’s causing a bigger erosion…leaving the community susceptible to wave action when we have big storms,” said Thompson.

Thompson also stressed how this unique resilient infrastructure project can serve as a global model for combatting climate change.

“Given what we saw with Hurricane Maria in 2017, I think storms of that nature are just our new reality and we have to start thinking more globally. And I do literally mean globally as a world to go and figure out how we’re going to kind of reverse course here,” said Thompson.

New York City is an enormous and delicate ecosystem. The environmental solutions being put in place may create models for the rest of the world to look to in the wake of climate change.

“An oyster isn’t going to solve climate change in New York City,” said Poniatowski. “But we’re hoping that this kind of mindset switch is going to help start initiatives or help start action on people’s hearts.”

New York waterfront on Coney Island.