The Unequal Price of Peaker Power

Communities Fight Back

By Eliza Mitnick

Suga Ray remembers first noticing the red and white striped smokestacks as a kid riding his bike and playing basketball with friends. The tallest smokestack on the Ravenswood Generating Station, called “Big Allis”, looms nearly one mile high. He shakes his head and looks up at it now. “Health is the biggest issue in Queensbridge,” he says. It’s the cost of living in such proximity to this highly toxic type of power plant.

Nineteen of the 24 power plants around New York City only turn on a few weeks each year, during the times of peak energy use. They are called peakers, for short, and they use natural gas turbines to produce electricity. Ravenswood is the state’s largest peaker power plant, and it can produce twenty percent of the city’s peak electrical needs. When its peakers turn on, mainly during heat waves and cold spells, it spews out the greenhouse gasses nitrogen and sulfur oxide as well as particulates, which are tiny bits of liquid and solid droplets. Breathing in these pollutants, especially the particulates, greatly increases the risk of respiratory disease in adults and children.

The Ravenswood Generating sits just feet away from a playground in Queensbridge.

Ray spent twenty years of his life here in Queensbridge, the largest public housing complex in North America. “This is where I grew up. This is where I spent twenty years of my life… This is home.”

Queensbridge opened in 1939 and is home to around 7,000 mostly Black and Latino residents, with a median household income of $15,000. In 1963, Ravenswood was built directly across the street from the perimeter of the houses. In New York, and the rest of the country, peakers are typically located next to poor communities of color like Queensbridge.

Suga Ray moved to the Queensbridge Houses when he was two years old.

This area of Western Queens, as well as other highly polluted neighborhoods such as the South Bronx, have been dubbed “asthma alley” for their disproportionately high rates of respiratory illness. During the first wave of the pandemic, of the 800 people infected with the virus in Queensbridge, a staggering 4.1 percent died, about double the citywide rate.

“I know a lot of people in my personal life who have died. But I’ve never seen as many people die in Queensbridge as from Covid,” says Ray.

He attributes the high death toll to the continued toxins the residents are breathing. “You can look and see the thickness and the fogginess,” he says while standing in front of the long thin smokestacks.

According to Community Health Profiles from NYC’s Department of Health, the South Bronx, which is surrounded by four peakers, has an asthma hospitalization rate three times the rest of the city.

“Too many people are suffering with respiratory issues. By no fault of their own, only because of where they live,” said Mychal Johnson, co-founder of local activist group South Bronx Unite. “If they lived in more economically affluent communities, they wouldn’t be suffering.”

Members of these frontline communities, like Ray and Johnson, wonder why the plants around them have existed for so long if the science is clear on the dangerous health impacts. As with most issues, financial incentives could be behind the continued operation of peakers. Ravenswood, originally owned by Con Edison, was passed down to different private corporations over the decades. In 2017, LS Power, a private equity firm, took ownership of the station. Peaker power plants are often owned by private equity firms who make hundreds of millions of dollars a year from ratepayers, even though these plants stay dormant most of the year.

The Clean Energy Group, a national nonprofit organization, has been working on understanding the economics of replacing peaker plants with renewable energy. “We’ve seen there’s a lot of bad actors in the energy world,” said Seth Mullendore, the vice president of the group. “Particularly with these hedge funds that are focusing on the dirtiest fossil fuel infrastructure that they can find as others are trying to offload it. And that’s very true of peaker plants. The goal of these firms and the goal of the gas industry is to be the last one standing.”

The PEAK coalition—comprised of The Clean Energy Group, New York City Environmental Justice Alliance, New York Lawyers for Public Interest, The Point CDC, and Uprose—has joined forces to advocate for the closure of peakers. They recently published a report showing that replacing peakers with clean energy would save ratepayers one billion dollars by 2035, and create an additional billion dollars in savings from health impacts. To do this, however, several other power sources must be available to meet those moments of peak energy demand, which engineers agree is possible.

“The highest emission rates per megawatt hour of electricity generated are your peakers,” said Elena Krieger.

Krieger is the director of research at the Physician Scientists and Engineers (PSE) for Healthy Energy. With a PhD in mechanical and aerospace engineering, she researches the technology behind replacing peakers with battery storage. Peakers respond to surging demand quickly, in five to ten minutes. “Well, a battery can do it almost instantaneously,” said Krieger.

Mullendore agrees that batteries will be a key component in replacing peakers. They have the ability to store clean energy from a variety of sources, such as solar and wind, and in Ravenswood specifically, the infrastructure connecting peakers to the grid can be retrofitted to accommodate batteries.

A transformer at the Ravenswood Generating Station can be repurposed to serve a clean grid.

“Western Queens gave me everything. I was able to aspire to do the things that I dreamed of doing when I was a little kid,” said Costa Constantinides.

Born and raised in Astoria, also considered part of “Asthma Alley,” he is now the CEO of the Queens Variety Boys and Girls Club after serving seven years on the City Council and chairing the Committee on Environmental Protection. “Astoria provides about 55 percent of the city’s power. And with that came a very sort of egregious cost.”

In 2019, the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act set forth the goal of bringing peakers offline by May of 2023.

“It’s an exciting possibility, right?” said Constantinides. This transition would include building renewable energy resources in the city, siphoning renewable energy from upstate or other states to be stored in batteries, and importantly, retrofitting our large buildings, which create two-thirds of energy emissions in the city.

“If we can do all three things in unison over the next decade, we have a real shot here at meeting the goals of the CLCPA, creating thousands upon thousands of jobs and breathing easier,” Constantinides said.

In October, however, the movement around shutting down Ravenswood suffered a major blow. The New York State Energy and Development Authority (NYSERDA) rejected a proposal to make all outputs from the Ravenswood Generating Station renewable by 2026. The proposal had outlined a plan in which Rise Light & Power would contract with renewable energy developers in upstate New York to build the Catskills Renewable Connector, bringing wind and solar energy to Ravenswood for dispersal to the city. Constantinides suspects that bureaucratic red tape and warped budget priorities may be behind this failed effort to shut the plant.

Advocacy groups and politicians have said they will continue to pressure NYSERDA to reconsider the Ravenswood proposal. After all, transitioning this plant is necessary to remain on track for meeting the CLCPA’s goals of shutting down peakers by 2023.

For now, however, those living closeby must continue to bear the burden of dirty energy creation as they take each new breath. “When they need to find money and push past red tape they do it,” says Suga Ray. “We can’t be afraid to continue to bring this issue to the forefront and hold people accountable.”

Can we see stars in NYC?

Light pollution in NYC

By Giorgio Ghiotto

Can we see stars over NYC?

Immersed in the silence of the bay, Susan Harder is lying under the Milky Way. Here, just two hours from New York City in the Hamptons, the night sky is still fully preserved.

Harder, together with the International Dark-Sky Association (IDA), has been promoting solutions for light pollution for the past 25 years.

Light pollution is a side effect of modern civilization and it is defined as the unnecessary, excessive or inefficient use of artificial light, causing severe consequences for the environment, human health, and wildlife preservation.

According to 2001 report in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, nearly two-thirds of the world populations and 99% of the European and North American citizens live in areas where the artificial lighting status surpasses the threshold set by the International Astronomical Union, meaning that the night sky is 10% brighter than it should be at its natural condition.

“Light pollution is a visual embodiment of vested energy. We estimate that billions of dollars of wasted energy per year are literally escaping into Space,” said Ruskin Hardley, the executive director of IDA.

Light pollution is mostly generated by wasteful use of energy, which produces catastrophic economic and environmental consequences. According to the International Dark-Sky Association, around 13% of residential electricity use in the United States is destined for outdoor lighting and nearly 35% of outdoor illumination is wasted due to unshielded or poorly-aimed lamps. In particular, the economical waste adds up to 3.3 billion dollars and the environment suffers from the release of nearly 21 million tons of carbon dioxide.

Replacing the outdoor light system with energy-efficient lighting systems, through the use of dimmer controllers and motion sensors “can save 7 hundred million metric tons of carbon emissions, that is the equivalent of 16 and a half million passenger cars being removed from the road,” according to Ruskin.

Scientists have come to the conclusion that one of the main reasons for the increase in light pollution over the world is the spread of white LED lights for outdoor lighting.

“The great [cause] for lightning problems that we have now is the advent of LEDs, that are fantastic for saving energy but people don’t understand: they are blue,” said Harder.

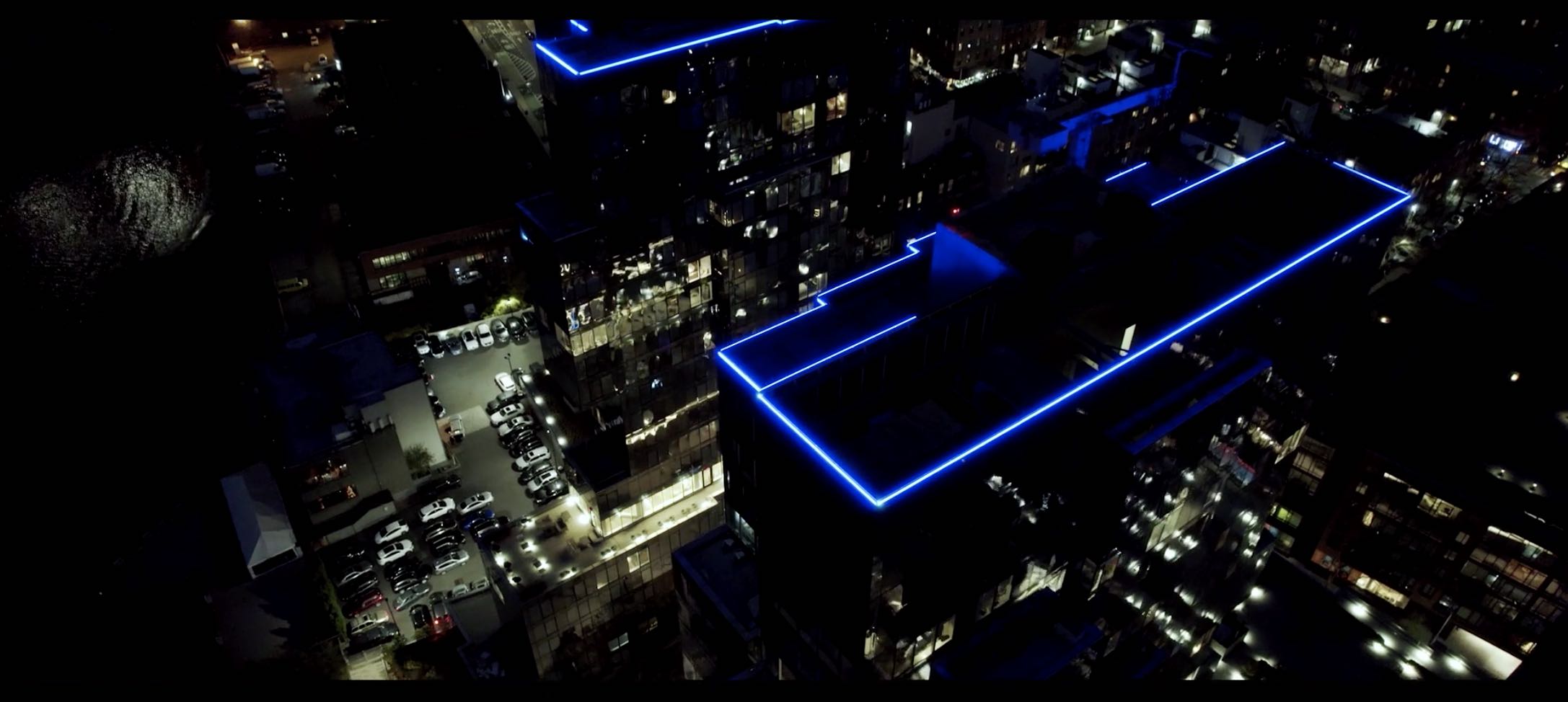

BLUE LED in Williamsburg

LEDs are dangerous because of blue light, which has shorter and more pervasive waves and scatters easily in the atmosphere. Cold LEDs cause different kinds of pollution. They are glare (a disruptive light that shines horizontally); light trespass (the undesired shining on adjacent areas); and skyglow (a halo resulting from the light scattered by the atmosphere).

Furthermore, this has a significant impact on human health. According to the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), artificial lighting is responsible for the alteration of the regular day/night cycle, known as the circadian clock, which impacts processes like hormone production, cell regulation, and brain wave patterns. Disruption of the circadian clock is associated with many medical issues, such as sleep disorders, depression, cardiovascular conditions, and, in some cases, even cancer.

Though humans are more exposed to indoor LEDs, an example of the direct impact of excessive outdoor lightning on human health is the fact that the management of light positioning and regulations is causing intense physical issues. Light trespass in a private apartment is the main cause of insomnia and the deterioration of the natural body cycle because of the confusion created between the shift of night and day.

Robin in the Bronx

“The LED that has been installed is really bright. The light is not going exactly where it is supposed to and it is transposing into the building,” said Robin Schwartz, a high school math teacher in the Bronx who is also an activist against light pollution. “When leaves come off the tree, light doesn’t have any filter and if you live on the first or second floor, you are affected by the NYC street lights.”

If linking artificial light to insomnia is intuitive, it is still debated if there is a connection between nighttime illumination and cancer risk.

“We do know through our studies that if you expose people to light at night they will suppress the hormone melatonin,” said Maria Figueiro, program director at the Lighting Research Center of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, NY.

Many scientists believe that the key to understanding the link between night shifts and breast cancer risk is to be found in the inhibition of melatonin production caused by exposure to artificial light. Melatonin is a hormone, secreted at night, which plays a crucial role in the regulation of the biological clock.

“Shift workers stay awake at night and are more likely to be exposed at night. The hypothesis is that they are at high risk for cancer,” said Figueiro.

Light pollution has also negatively impacted wildlife. It can alter foraging behaviors and breeding phases in urban landscapes as much as in rural areas.

“Artificial light drags down birds down and distract them. Oftentimes birds land in big cities in New York and when they wake up the next morning they slam into windows,” said Kathryn Heintz, executive director of the NYC Audobon. “If it weren’t for artificial light, birds would probably keep going and they would keep going from natural area to natural area.”

As Heintz suggested, birds suffer from severe forms of stress and disorientation caused by skyglow, and some of them often fall dead to the ground or slam into illuminated buildings. They are attracted by lights but they are not able to correctly estimate distance and danger.

Last September, more than 300 birds crashed into glass buildings of New York City, including the World Trade Center, according to the Associated Press.

Bats are impacted too. The effect of skyglow makes it hard for them to properly see and hunt their prey and to get adequate nutrition.

Sea turtles suffer from different forms of disorientation caused by night illumination: females find it hard to reach the beaches where they intend to nest and they are often confused by the bright lights.

There are some solutions, however.

Shielding could prevent skyglow and light trespass since it would cover the upper part of light bulbs and direct the light only downwards. A change of light temperature is strongly needed and white LEDs need to be progressively set apart by warmer lights. Even timers could help to prevent waste of energy since they would activate lamps only when needed.

The government could play a crucial role in balancing environmental and urban needs. For example, the Tucson Law grants residents right of access to the night sky in Arizona. It was a decisive step forward and Susan Harder and the Dark Sky Association are doing their best to bring a similar law to New York City.

“It’s a human need and a human right to be able to see and enjoy the stars,” said Harder “It’s an ancient tradition handed down and it’s very important not only in the country but also in the city.”

Star photography in Long Island