The city of Utica might be the realistic version of Macondo in “One Hundred Years of Solitude” by Gabriel García Márquez. But when the city fell into poverty from being one of the richest city in the US, it’s was refugees who came and saved it.

But the recent anti-refugee storm is putting pressure on the city and the muslim refugee community.

Let’s take a look at what kind of community it’s, how their life is like, and feel.

The Renewed American Dream

– Teng CHEN

Utica, once nearly dead has come back to life again, not because of government or gangsters or the glitterati of the past, but because of refugees from war torn parts all around the world.

Azira Tabucic, a refugee from Bosnia, still remembers the devastation of the city at the time when she arrived. “Every house on the street looked like burned when I first came here in 1994,” she said. “It looked like disaster, honestly. I got scared. You can’t even imagine.”

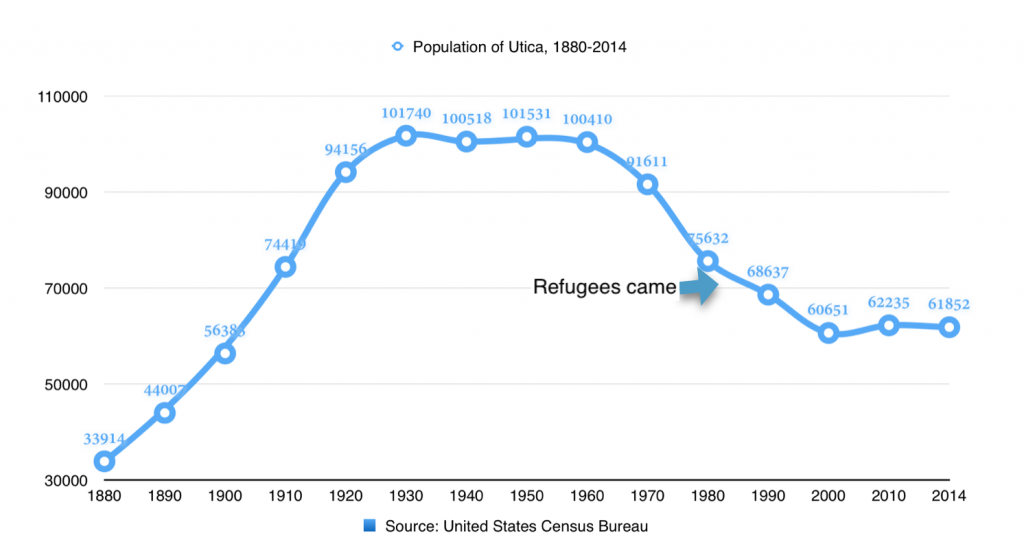

Once America’s burgeoning textile empire on the Erie Canal in 19th and early 20th century, Utica suffered a decline when cotton was no longer a prime product and labor moved out to cheaper areas. The population dropped. The “Sin City”, once a home to celebrities, mafia godfathers, girlfriends of crime czars in New York City, was left with gang warfare and poverty.

But now that history is turning around in Utica, and refugees are the light holder.

Restaurants, stores, and markets owned by refugees from Vietnam, Lebanon, Mexico, East Africa, and Bosnia are pumping new blood into Utica’s economy. The city is benefiting from the strong entrepreneurial spirits of refugees and immigrants. According to Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service, immigrants are 30 percent more likely to start new business. Throughout the year cultural festivals and New Year celebrations from different ethnic groups rotate to change the forlorn look of Utica.

Utica has now welcomed 15,554 refugees since it first opened its door in 1979. The city became home for refugees mostly by accident, after resident Roberta Douglas helped an Amerasian child from Vietnam war and launched her work with refugees. With local help from churches and government, Douglas founded the first and the only refugee organization in Utica: Mohawk Valley Resource Center for Refugees (MVRCR).

Shelly Callahan, the executive director of the center, said, “Refugees are critical for the recovery of economy and also vital to the social fabric of the city.”

In 2010, the city’s population increased slightly 2.6 percent breaking a 50 year decline. Foreign-born residents constitute 17.6 percent of the city’s population. The number of congregations have soared from 35 to 1000. Together with the population growth, the labor shortage was filled; the once abandoned and burnt houses are refurbished and revitalized.

Tabucic, a refugee from Bosnia, explained the positive effects that a refugee adds to a community, “As a refugee, you once lost freedom and suddenly somebody gave you the chance to come to the most beautiful country in the world and offered you a job, education, a family, and to sleep in peace. You have that on the back of your mind, everyday, I do, think about that.”

Among the many successful refugee stories in Utica, Mowlid Hussein’s story although ordinary can also be startling.

“Yes, call me whenever you need me, no problem,” says Hussein who seems forever ready to jump into the next job, and make the next friend, and earn their trust. Hussein, 31, comes from Somali Bantu tribe, which suffers from a long history of slavery and ongoing civil wars.

Since coming to the US in 2003, Hussein has now successfully purchased three houses and pays $3,400 in property taxes each year. “Most of houses are bought by refugees in Utica,” says Hussein while driving in the eastern part of the city. “And every year the number of refugee property adds on.”

The story of Hussein coincides with a study about fiscal Impact of refugee resettlement in the Mohawk Valley conducted in 2000 by Paul Hagstrom from Hamilton College in Utica. Hagstrom’s research focuses on immigration and immigrant policy. In the study, Hagstrom points out that refugees usually are a net cost in the early years, and then yield benefits for many years to come. After 13 years, the cumulative net benefit of a single household becomes positive and remains positive every year after. The primary fiscal benefits accruing from refugees stems from their participation in labor markets, consumption of local goods, and real estate markets, according to the study.

Not only do refugees contribute to the economy, but also to the social vibrance in less visible ways. Kadie Lavare, a high school student from Utica, is grateful for the inspiration brought by her refugee classmates.“I felt like every one here has a story behind themselves, and what they went through, it’s not just one race is all races,” said Lavare, adding, “Even if you don’t like the race, they still went through something, something tragic and heartbroken, but there is still some beauty comes out of it. I think it’s inspiring because no matter what somebody has been through, in the past, they can always turn it around in the future.”

But for other residents such as Tom Welch, a Vietnam Veteran, the determination to help refugees comes with a specific motivation, “there we kill, here we help.” Welch started as a volunteer at the refugee in 1989, when it was still firmly focused on Amerasian children, and is now a receptionist at front desk. Although he proudly sports a cap with Vietnam Veteran blazed on the front he doesn’t want to read anything about the War anymore and instead concentrates on helping refugees from war zones which he was once a participant of.

Now 69 percent of residents in Utica show support for refugees, according to a polling study commissioned by MVRCR in 2013. Utica is honored as “the town that loves refugees” by UNHCR, a UN refugee agency. But this praise doesn’t mean there is no resistance against the influx of refugees.

Local resident Keith Foster, who has lived in Utica for 58 years, complained. “I don’t blame people who come here, I blame the government to allow these people to come here. They don’t have to be employed, some of them walk around, wear the costumes from their countries, and do nothing. But government takes care of them, and I don’t think that’s right,” he said.

Foster’s resentment coincides with the rising anti-refugee sentiment across the country which questions the costs of resettlement, especially at a time when the economy totters, budget falls, and the unemployments rate is still high.

Online conservative blogs such as Refugee Resettlement Watch have been frequently challenging refugee resettlement programs about the necessity of the cost, how many and what kind of refugees the US should take, and national security which might be harmed by bringing in refugees, pointing especially to Muslim refugees.

After Paris attack and the recent terrorist shooting in San Bernardino, the fear of national security being undermined makes the anti-muslim refugees sentiment stronger. So far, 31 states have said they are not going to take any Syrian refugee.

The heated discussion did blow over the still weary and grey Utica and its refugee center.

“I think it has influenced us because some politicians were making people connect refugees with terrorist and it’s wrong. It’s tragic and shameful, because refugee is the person who flee from the very violence and refugee is probably the person you should fear the least, in terms of someone who comes into the country from another country,” said Callahan, the executive director of the refugee center.

Different from Europe, the US has the right to choose which refugees to come in. On average it can take 18 to 24 months of screening by the department of homeland security, the State department, the CIA, FBI, and rounds of personal interviews. “Refugees are particularly the most thoroughly vetted people to enter this country from other place,” said Callahan.

According to a local resident who has knowledge of how the recent issues have influenced the center, the center has been quite busy dealing with phone calls from residents asking the center to stop taking refugees. “I feel worried about the center. It’s quite unfortunate because people only live in their own bubble and can’t see the positive effects brought by the refugees,” said this resident who doesn’t want to be named.

But for some local residents in Utica, the resistance comes with life details. Thomas Evans, 28, the owner of a wig shop in downtown Utica, has no objection towards refugees. “It’s ok they come here because they want a better life. They don’t bother us, we don’t bother them,” he says expressing a common feeling shared by some residents. But when talking about cultural difference, Evans grew a bit irritated and complained some refugee clients asked them to turn down Christmas music only because they are from other countries which don’t celebrate Christmas. “They keep in their own small community. They want us to be what they want to be,” he said.

Evans points out a key question in evaluating the success of a resettlement program: refugee integration. According to the report Resettlement At Risk by HIAS in 2013, “The U.S. is the only major resettlement country in the world that does not have federal integration benchmarks. In the U.S., professional advancement, social bonding, civic engagement, education, and health are not measured, and refugees and receiving communities have had no opportunity to help define what successful integration means for them.”

Education also plays an integral part in integration. Callahan admits that the Utica school system is “bursting at the seams” as it is discovering that population growth can be as big as problem as population decline.

Recently, Utica’s Proctor High school was sued twice in separate discrimination suits filed by the New York Civil Liberties Union (NYCLU) and New York State for turning away refugee teenagers over 16 years old because of their inefficiency in English. The school argued it was not discrimination instead there is not enough funding.

Despite the lawsuit and its outcomes, the education of the student still remains a problem, as they come from a different background, lack of English efficiency, and have different educational level. Susan Young, one of the co-counsel in the NYCLU lawsuit and who works closely with these refugee students, hopes there is more which can be done in regard to the education of refugee children.

And Young said she doesn’t want to leave people the impression that refugee students are demanding something which they are not entitled, “The students and families we met, are very anxious in helping themselves, they are not waiting for the the government or anyone to rescue, they are very involved in bettering themselves.”

Winter is drawing nearer. The chilly wind blows over the once sin city harder. Empty shops and run down houses in downtown Utica still await new owners. The city’s weary downtown still sits in contrast to this renewed American dream refugees embrace, a dream which sometimes seems forgotten but is not in a place that once seemed doomed.

And Hussein, who has crawled out of the slave history and wars in Somali, is buying his fourth house in Utica.