Violence Interrupters

Narkwor Kwabla

‘We Were the Ones Hurting the People. Now We’re the Ones Making the Change’

How Cure Violence Combats Crime

By Narkwor Kwabla

Violence interrupters walk through the Fort Greene projects

FORT GREENE— On Myrtle Avenue, Anthony Mabry— known by his nickname, as ATL— and his team of six head out to the Fort Greene and Farragut housing developments. Clad in camouflaged puffer jackets with orange-stripes on the arms and G-M.A.C.C. boldly embroidered in white and a red umbrella on the back, this team is canvassing for early signs of violence in the area.

‘‘We were like them at one time, we were the ones with the guns, we were the ones selling drugs, we were the ones hurting the people now we’re the ones making the change,’’ he said.

It’s been two weeks since the last shooting incident in this neighborhood. As police patrols increased, ATL and his team also frequented the area to talk to residents.

We are the change, so when they see us doing this, they will know there is a better life,’’ he said.

Violence interrupters Keith Davis, Carlos Jones interact with resident.

They are familiar faces in the community.

Some were affiliated with gangs. Five out of the six canvassing on this day have been imprisoned for various crimes.

‘‘We have about a 100-years experience here,’’ said Carlos Jones, a former inmate and violence interrupter with G-M.A.C.C.

‘‘But we’re not glorifying that, it’s time to build what we destroyed,’’ Richard Davis, another violence interrupter, added.

This team is part of Gangsta’s Making Astronomical Community Changes, G-M.A.C.C., a group operating on the Cure Violence model, introduced in Chicago over two decades ago to reduce gun crimes in the city.

A professor of epidemiology at the School of Public Health, University of Illinois and a founder of Cure Violence, Gary Slutkin pioneered the concept that violence should be ‘‘treated as a contagious disease.’’ He was of the view that violence should be approached as a public health menace using the disease detection and prevention methods.

In 1995, the pilot of this project called CeaseFire was launched and was later changed to be known as Cure Violence. The project mostly works with former gang members and ex-convicts who are trained to be violence ‘‘interrupters and outreach workers.’’

‘‘This is a very typical public health approach and so for instance if we are addressing a contagious problem of HIV/Aids and we want to address the highest risk, one of the group of highest risk might be sex workers,’’ said Charlie Ransford who is Director of Science and Policy at Cure Violence Global ‘‘With a contagious problem of violence is just the exact same thing, it’s not like we are going to have people from outside, we are not going to have police officers coming in but we are going to hire from the community to reach the people we are trying to reach in the most influential credible way possible.’’

Violence interrupters move into the community and try to defuse tension after a shooting incident. They do this by talking to all sides of the conflict, convincing them of the reasons why they should not retaliate. The interrupters also mediate ongoing feuds between rival gangs and personal disputes that are likely to spark violence.

The outreach workers serve as confidants to these high-risk individuals identified in the community and connect them with employment opportunities and other resources.

Then there are the hospital responders. They are not medics but they work with local hospitals to assist victims and families in trauma.

In New York City, the Mayor’s Office to Prevent Gun Violence has worked with nonprofits in 22 precincts since the city adopted the program in 2010. G-M.A.C.C. is one such organization with offices in East Flatbush and Fort Greene.

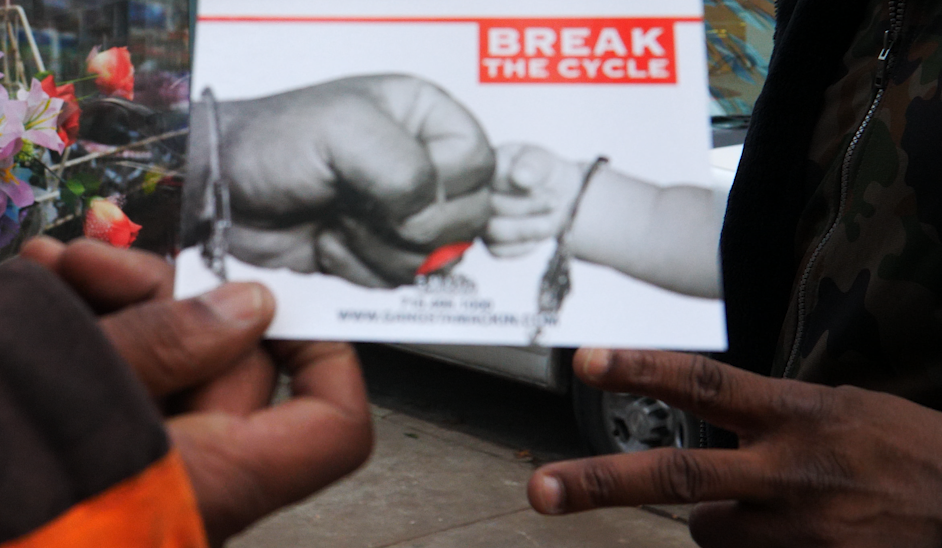

Violence interrupters work with high-risk participant to break the cycle of recidivism.

Violent crime has declined in New York City over the last decade and 2017 research by the John Jay College of Criminal Justice showed a ‘‘significant reduction’’ in shootings and killings in areas where the Cure Violence program was being implemented, compared to communities with similar demographics that had no Cure Violence program.

‘‘This is not a cure all, a solution for everything. But you can have an effect on the rate of violence by investing in a well operated fairly affordable program,’’ said Jeffrey Butts, Director of Research and Evaluation at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

The research was conducted in the South Bronx and East New York. Shootings in the two neighborhoods had declined by 63 percent. Before the introduction of the Cure Violence program, at least 35 gun injuries were recorded in the South Bronx but that had dropped to 13 during the year under review. In East New York, gun injuries dropped from 44 cases to 22.

The researchers also examined the attitudes of young men towards violence and trust in police. In the neighborhoods that had Cure Violence, Butts detected a ‘‘meaningful and statistically significant increase in trust in the police in neighborhoods with Cure Violence.’’

‘‘Which is interesting because sometimes the police department themselves have an image of the Cure Violence program which would suggest that it’s anti-police. I think that’s probably true for some people,’’ said Butts. ‘‘But as phenomenon the cure violence approach is necessarily not anti-police and if its managed well and the city invested properly with enough money to hire some people you can have an effect on shootings.’’

Cure Violence has gone beyond the borders of the United States and it’s been replicated in some countries in the Middle East, Africa, Europe and Latin America.

Ransford believes ‘‘cities looking at the most effective way to influence behavior’’ will resort to a public health approach as opposed to the ‘‘police crackdown that has a lot of problems.’’

It’s not just community violence, it’s domestic violence, it’s suicide, it’s terrorism, it’s mass shooting events and also riots,” said Ransford. We were recently consulted with people involved first hand in the riots in Hong Kong for instance.”

He said demand is ‘‘huge’’. People are realizing this is an approach that has a lot of potential and the only thing holding them back is the ‘‘limited capacity’’ to respond to all requests.

As it stands now, the program hires at least some people who have been in street gangs before or incarcerated, which is supposed to make it easier to gain ‘‘trust and credibility’’ in the community they serve.

The problem is these are people ‘‘police are inclined to distrust,’’ according to Butts.

The interrupters job is to intervene before any crime takes place.

But the inappropriate behavior of a couple of these violence interrupters in Chicago, who were arrested for criminal offenses including domestic violence, sexual misconduct, theft and working with gangs, raised questions about using people with past criminal records. The city reacted by cutting funds to 13 of 14 local chapters of the Cure Violence program.

And in Louisville, Kentucky two of the city’s violence interrupters were arrested in March for rape. Another was indicted for drugs. Local city councilman called for the program to be ended. But the Mayor’s office defended the program arguing that it has ‘‘ achieved substantial results in violence reduction.

Most of these programs rely heavily on state funding which makes them politically vulnerable.

Butts said these cases ought to be dealt with as individual cases.

‘‘People need to appreciate that this can be an asset that can be valuable to a neighborhood but it has to be grown and nurtured,’’

He also believe Cure Violence ‘‘could persist and become a regular part of public safety’’ in the future. But cautions that the program’s survival is dependent on ‘‘research evidence to support the effectiveness and cost effectiveness’’ of it.

‘‘Anecdotes and stories are good for the movement but they won’t protect the movement when critics come along if people start to look skeptical if you don’t have good solid evidence the movement would die out so it’s in a critical phase right now,’’ said Butts.

Gangs United

Kyla Milberger

‘My Mother Didn’t Raise a Savage’

How Gang Members are Changing the Narrative for What it Means to be in a Gang

By Kyla Milberger

EAST FLATBUSH― In the Brooklyn neighborhood of East Flatbush, there is a non-profit organization called Gangstas Making Astronomical Community Changes (G-M.A.C.C.), where active Blood and Crip members work together to prevent gun violence in their community.

There are 33,000 gangs across America today ― sophisticated and well organized. They use violence to control neighborhoods and can make money illegally through robbery, drug and gun trafficking, prostitution and human trafficking.

From the 1850s to the 1930s, there was a massive influx of migrants into the United States. Approximately 38 million people migrated to America from all over the world ― mostly from Europe. The large scale of migration caused different social classes to form. People who were disadvantaged and poor lived separate from the richer and higher classes.

Social, ethnic, and racial conflict abounded amongst lower class communities. Young people formed groups in their neighborhoods and schools as a form of alliance and protection against the escalating conflict. Eventually, the groups evolved into modern-day gangs.

Although there are many different types of gangs, the most well-known and widespread in the United States are street gangs. The Bloods and the Crips are the most prevalent and notorious street gangs in America. Both formed in Los Angeles, California in the 1960s and 1970s and have since migrated to different cities across the country, such as New York City and Chicago.

Dean Martin, who is also known by his street name, Dro, is an active Blood member in New York City. He works for G-M.A.C.C., which is mainly run by current gang members in both the Bloods and the Crips. The organization’s fundamental goals are to change the individual behavior among both Cure Violence (CV) participants and high-risk youth and to denormalize brutality by adjusting the broader social norms that perpetuate violence.

G-M.A.C.C. participants pose for a group photo.

Cure Violence is a public health initiative that seeks to reduce gun violence by treating it as a disease that can be prevented.

“As an organization our focus primarily is to minimize the shootings and murders in our communities, stop the killings from happening and change mindsets and create a healthier and safer community for our young people,” said the founder of G-M.A.C.C., Shanduke Mcphatter.

These previously incarcerated gang members help to denormalize violence in East Flatbush by canvassing in the neighborhood, holding entrepreneurial events for youth, and responding to the shootings that happen in the area. This keeps the staff out of prison and prevents high risk youth from getting involved in gang and gun related violence.

According to Dro, most of the people who join gangs are coming from broken homes and aren’t part of the “nuclear family” structure ― meaning the family that has two parents and two kids.

“That’s the normal story. Everybody hits… with a father being in prison, mom not working or probably strung out on drugs.”

“That’s the normal story. Everybody hits… with a father being in prison, mom not working or probably strung out on drugs. It becomes no family structure. You might come in the house and there’s nothing in the refrigerator,” Dro said.

Dro said this becomes normal and families struggle to survive.

Andre Robbinson, who is also known by his street name, Dadeo, was raised by his grandfather until he passed away. He is an active member in the Crips. He lives in New York City and works along with Dro for G-MACC. He took to the streets when he was only 14 years old, where he found a new “family,” with the Crips.

Every gang lives by a set of codes or standards that represent the group. Blood stands for Brotherly Love Overrides Oppression and Destruction, while Crip stands for Community Revolution In Progress.

A childhood photo of Andre (Dadeo).

“I believe it became violent over power because everybody probably wants to be in control because we are all fighting for the same thing,” Dadeo said. “It’s all about making a change in your community and that’s what we’re trying to get through with the program, Cure Violence.”

Gangs like the Bloods and the Crips dominate the drug-trade market. Gang members convert powdered cocaine into crack cocaine and make most of the PCP that is available in the United States. They also produce marijuana and methamphetamine and are involved in smuggling large quantities into the United States from other countries.

A group photo of Andre (Dadeo) and other Crip Members from the 90s.

Dadeo said excessive drug trafficking and trading causes a lot of the gun and gang related violence in the United States because the gangs are fighting for “power” and “control.” Dro was personally involved in the drug trade business, which landed him a 10-year prison sentence.

“What led up to my incarceration was me partaking in dealing drugs. It got to a point where it became a war over the territory because of the money,” Dro said. “A few attempts were made on my life. Fast forward, I find out a little bit of information, and I reacted on it, and with that, I end up going to jail for 10 years for murder.”

Dro was only 20 years-old when he was sentenced. Prison gave him the opportunity to turn his life around. Dro said he missed seeing his siblings grow up, and he could only see them through pictures.

“Things like that, it takes a toll on you emotionally,” Dro said.

Dro started to rehabilitate himself in prison. He realized that he didn’t want to be the “savage” he was turning into.

“My mother didn’t raise a savage. The streets just embedded certain things in me that I didn’t know how to control at the time because I was so young and naive,” Dro said.

Both Dro and Dadeo joined their gang when they were just children. They were looking for acceptance, family, and a way to support themselves when nobody else could.

“You know a lot of us is just like a bunch of misfortunate kids just gathering together and coming together and trying to make something of themselves and fight for a bigger cause, but sometimes you get lost in the midst of the cause, especially when the cause gets bigger and bigger and bigger,” Dadeo said.

Police Distrust in East Flatbush

Sara Herrin

When Street Cred Can Land You a City Job: Cure Violence Initiatives are Sweeping NYC to Help Reduce Rates of Gun Violence

By Sara Herrin

EAST FLATBUSH― On the corner of Church Avenue and East 55th Street, a large rust-colored box sat anchored to the sidewalk filled with candles, some still lit. Mahnefah Gray took a look inside at a photo of her brother when he was 15 years old. The photo must have been taken in 2012, Gray recalled, just a year before two plainclothes NYPD officers shot a total of 11 rounds at her brother, Kimani Gray.

Accounts of the altercation vary. Some say Kimani was turned away from the officers when the shots were fired, while the NYPD reports that a .38-caliber Rohm revolver, found on Kimani at the scene, was pointed at the officers when they shot their first rounds.

As Gray walked back to her office after visiting her brother’s memorial site on a recent November morning, she paused. “The cops are supposed to protect and serve us, correct? And help the community. For us, it’s not like that. It’s different.”

Tensions have historically simmered between the neighborhood’s predominately black residents and law enforcement. Distrust in the police remains high.

Mahnefah Gray in front of Kimani Gray’s memorial site

Curing Violence in East Flatbush

In 2013, when Kimani Gray was shot, East Flatbush was a top three New York City neighborhood for gun violence. At the time, small grassroots organizations like Life Camp and Man Up! Inc. were emerging in what was being called a Cure Violence model 一 an approach that amplifies citizens’ abilities to prevent crime and gun violence without police intervention.

Cure Violence began in Chicago in 2000. The model relies on “credible messengers,” often rehabilitated gang members and other individuals with a criminal record, to stop violence in their communities before it starts by deescalating small disputes and restructuring community norms. The idea is that violence-prone individuals are more likely to respond to their peers or mentors than the police.

Although there is no way to quantify the success of Cure Violence programs in isolation from other factors, the model appears to be working. According to the NYC Office to Prevent Gun Violence, the city-funded Cure Violence model organizations and accompanying services have contributed to a 15 percent decline in shootings in 17 of the highest violence precincts in the city.

The model was not always supported by city government, however. When Shanduke McPhatter began canvassing his Brooklyn community to preach anti-violence, he was just released from prison and on his own. He hoped that by speaking with at-risk youth and using his street credibility to interrupt potentially violent conflicts, he could prevent others from making decisions that would land them in jail.

McPhatter began doing this work because he knew firsthand how effective it could be. When he was deeply entrenched in street life and became involved in drug-related disputes, an acquaintance from his neighborhood was able to talk him down from committing a potentially life-changing shooting.

“I thought about how effective that was for me,” said McPhatter. “And I said I’m gonna come home [from prison] doing that.”

McPhatter began organizing in East Flatbush after the Kimani Gray shooting, when tensions with police were high and a discussion around how to prevent children from handling guns was at the forefront of community dialogue. His work gained the recognition of then-Council Member Jumaane Williams and the pair began canvassing together along with other neighborhood residents.

In 2015, Williams introduced McPhatter to the work that was being done within city government based on the Cure Violence model. The work aligned closely with McPhatter’s methods and mission.

That year, McPhatter received $250,000 through the City Council to start his own organization based on the Cure Violence model and G-M.A.C.C. 一 standing for Gangstas Making Astronomical Community Change 一 was born.

A New Government Office to Prevent Gun Violence

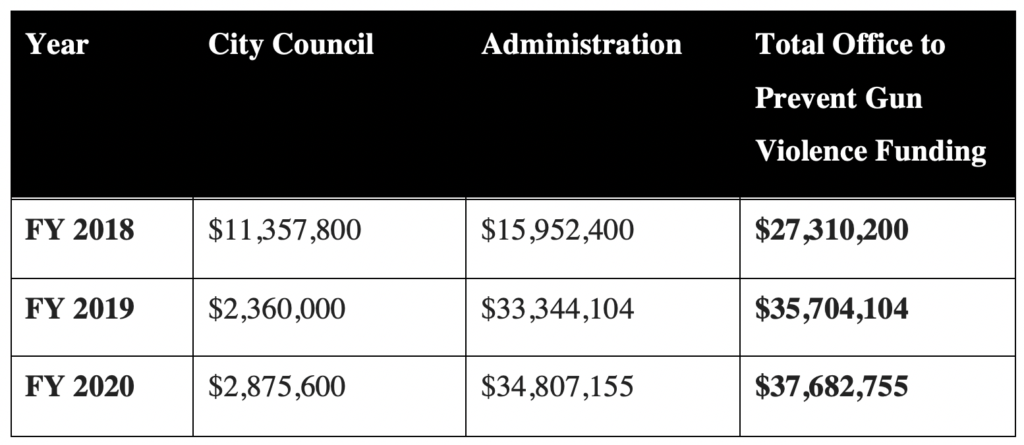

G-M.A.C.C. survived on City Council support until February 2017, when Mayor Bill de Blasio created the Office to Prevent Gun Violence within the Mayor’s Office of Criminal Justice. The Office received a total of about $27 million in its first year and is now set to receive just under $38 million in 2020.

Funding for the Office to Prevent Gun Violence

“Having the additional support from City officials really makes a difference,” said Tiffany Lamela, Deputy Director of G.M.A.C.C.. “We wanted to make sure that this wasn’t something that could just be removed at any given time.”

According to Lamela, the creation of the Office to Prevent Gun Violence has been especially beneficial to G-M.A.C.C. and the two other grassroots organizations, Life Camp and Man Up! Inc., who would regularly have to wait on the City Council to receive retroactive funding for projects prior to the Office being created. Now, she says, funding is more reliable and streamlined.

G-M.A.C.C. and the other Cure Violence initiatives in New York City are part of the Office to Prevent Gun Violence’s Crisis Management System. The Crisis Management System is responsible for deploying teams of messengers to mediate conflicts and connect at-risk individuals to services that reduce long-term use of violence.

The Office to Prevent Gun Violence network consists of 14 nonprofit partner organizations spanning 22 precincts within New York City. Members of the network are provided with wrap around support services including school conflict mediation, employment assistance, therapeutic mental health services, legal services, and access to an Anti-Gun Violence Employment Program, which employs 14-24 year old participants to conduct canvassing and community outreach. The Anti-Gun Violence Employment Program was created within Office to Prevent Gun Violence to support Cure Violence initiatives and currently employs about 300 youth per year.

Hailey Nolasco, Brooklyn Borough Coordinator for the Mayor’s Office to Prevent Gun Violence, oversees all of the Office’s anti-gun violence initiatives under the Crisis Management System for Brooklyn.

“We’re very community oriented,” said Nolasco. “When there is someone who has been shot or has been harmed, we go out there and we meet the families.”

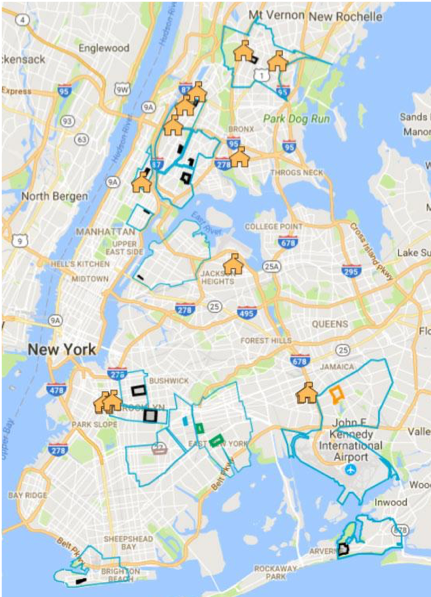

Cure Violence catchments in NYC via The Office to Prevent Gun Violence

All of the staff coordinating Crisis Management System sites are from the five boroughs served by the Office to Prevent Gun Violence, according to Nolasco, which is why she believes the coordination offices are so effective.

“It’s just a really interesting space because we really are invested in this. This is something that we understand, that we’ve probably experienced in our own lives as well. We’re not too far removed from knowing the issues that are happening.”

Does the Cure Violence Model Work?

The John Jay College of Criminal Justice has been following Cure Violence initiatives in New York City closely. One prominent study released by John Jay in 2017 examined the efficacy of two of the 18 Cure Violence sites that existed in the city at the time.

The study found gun violence trended down after the opening of the two Cure Violence programs, S.O.S. South Bronx and Man Up! Inc.. In the catchment area of the S.O.S. South Bronx site, gun injuries went down by 37 percent and shooting victimizations went down by 63 percent. In Man Up! Inc.’s catchment in East New York, gun injuries went down by 50 percent and shooting victimizations went down by 15 percent.

The study also found that Cure Violence programs were appearing to noticeably change community norms around the use of violence. Over the course of the study period, young men in neighborhoods with Cure Violence programs reported significant declines in their inclination to use violence to settle personal disputes.

Their job is incarceration, our job is prevention. There’s a difference.

More surprisingly, researchers at John Jay found that trust in police is higher in neighborhoods impacted by Cure Violence programs.

“In neighborhoods with Cure Violence we detected a meaningful and statistically significant increase in trust in the police,” said Dr. Butts, director of the Research & Evaluation Center at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice. “Which is interesting because sometimes the police departments themselves have an image of the Cure Violence program which would suggest that it’s anti-police.”

Despite heightened trust in police among communities with Cure Violence programs, McPhatter believes that there is still a long way to go before community members in higher crime neighborhoods see law enforcement as an ally.

“[The police] have to show us that they value our community first,” said McPhatter. “They have a job to do and we have a job to do. And I respect them as who they are, but we don’t work together…Their job is incarceration, our job is prevention. There’s a difference.”

Guardians of Staten Island Streets

Talgat Alman

On Staten Island, Nonprofits Hope to End Violence on the Street

by Talgat Alman

STAPLETON, STATEN ISLAND — There are at least two types of techniques to prevent violence and maintain peace in the contemporary world. The ultimate goal of the first method, known as symmetric, is to seize territories through violence and dictate peace. The asymmetric or information-centric method, however, seeks critical information in order to prevent violence. A nonprofit initiative called True2Life at Central Family Life in Staten Island prevents gun violence according to the asymmetric approach; they intercept information about potential conflicts and then interrupt them before it erupts into violence on the streets.

“There is no doubt that information is crucial in preventing violence. Therefore, we monitor everything; streets, people, social networks pages, everything that can lead us to violent conflicts,” said Michael Perry, 38, a program manager at True2Life. After Perry lost his father at the age of ten and his best friend after nine years to gun violence, he decided to join the group.

“My friend got shot and my father was stabbed on the street. I think about them all the time,” said Perry.

Alpha Kamara (NYU student) and the violence interrupters, True2Life

Trained workers of 12 men, mostly former gang members and the formerly incarcerated, not only monitor the Staten Island streets but also mediate conflicts using their own credibility. According to the violence interrupters, no one is born credible. However, “stand up” people can earn credibility in Staten Island.

“Credibility is everything on the streets. You do not have to be a former gang member or prisoner to be credible. You just need to be recognized by others. We know how to solve conflicts, and how to deal with people, even with gang leaders because we are credible,” said Malcolm White, a hospital supervisor at True2Life.

According to NYPD data, the number of shooting victims in Staten Island has increased by more than 11 percent and shooting incidents by 17 percent over the last year. The long term goal of the Cure Violence initiative is to decrease these numbers and improve the lives of Staten Island residents.

“Our goal is to carry positive messages. We want to provide Staten Island residents with the needed services. We do not want them to be incarcerated, instead, we want them to improve their lives,” said Perry.

Violence interrupters, hospital respondents, and mediation makers at True2Life work closely with the New York City Council. There are several several at-risk neighborhoods in Staten Island and The Council has sent True to Life to work in two of the most dangerous areas: Stapleton and Harbor.

The group provides residents with Legal Aid, mental health, and conflict resolutions. However, retaliation is the most difficult part of street conflicts.

“If someone got shot or stabbed, we gotta go to the hospital and talk to victims and their close ones. We do not want them to take revenge. It should be handled,” said Carlton Fisk, a violence interrupter of the program who spent more than a decade in prison prior to joining the group.

Rostiman Fitzroy, a resident of Stapleton, Staten Island, said that although the popularity of gang groups has waned over several years, some teenagers still want to join them.

“Well, young people just shoot each other for no reason because they want to look cool. I do not think that cure violence initiatives like True2Life can prevent conflicts in our neighborhood.”

True to Life’s managers said that unemployment and lack of social-economic programs cause gun violence. An unemployment rate in Staten Island is slightly higher, 4.1 percent, than the U.S average at 3.9 percent. Poverty, however, remains a problem on Staten Island’s North Shore.

“Listen, I understand the neighborhood residents. They are struggling and they have no jobs, and they have to do something to feed their families,” said Perry.

True to life has its own code of honor with a list of restrictions. If the group members break one of them, it will have consequences such as disrespect from the neighborhood residents.

“We never snitch to police about our people, otherwise, people will not trust us. Sometimes they can warn us about potential conflicts. I think we should give people a second chance even if they were involved in gun violence once, just like we were,” said Perry.

The violence interrupters say that the police are not able to eradicate gun violence, although they are well equipped. Stopping crimes on the streets is more difficult than it seems said Bob Gangi, Director of Police Reform Organising Project.

“There is no magic bullet to eradicate gun violence or any other social-economic problems. But if we want to reduce gun violence across the city to a large extent, the government should invest more in better schools, better housing programs, mental and medical health services so people will have a stable life. So people will feel valued in our society,” said Ganji.

Gangi said that a more holistic to dealing with crime is more effective than an emphasis on punitive sanctions and imprisonment that law enforcement currently uses. He also believes that in the end, peace on the streets will prevail.

“I think we will get rid of violence on Staten Island one day,” he said.

Treating a Wound through Hospital-Based Violence Prevention Programs

by Bohao Liu

STATEN ISLAND – Late at night, in the hospital, three young men lay on stretchers. They were sent there after a shooting accident. One of them was a young woman, Shanita Lopez.

“Three people were shot that night. It was me and two other people. I don’t know who shot me,” Lopez recalled. “One was shot in his balls and one was shot in his stomach, but I was in the hospital the longest because I got hit with a hollow, a type of bullet that once it hits, it explodes. They really didn’t know what to do with me in Staten Island, so they transferred me to another hospital, and I had to get like three to four surgeries due to the damage.”

In the hospital, physicians do their job to save Lopez and other individuals, but who can cure the violence rooted in the community?

Lopez now works for True 2 Life, based in Staten Island, which is a hospital responder and violence interrupter. True 2 Life offers 24/7 response to those admitted to emergency rooms for shooting and stabbing injuries. Hospital responders respond immediately to prevent retaliation.

In 1983, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention started to treat violence as a public health problem. They established the Violence Epidemiology Branch to focus public health efforts on violence prevention. In 1996, the United Nation’s World Health Assembly passes a resolution saying that violence is a leading public health issue in the world.

In New York City, one of the biggest cities in America, there has been an uptick in gun violence.

According to the NYPD, year-to-date numbers show total shooting incidents rose to 708 from 683 last year, a 3.7 percent increase. Shooting victims year to date rose 3.2 percent, from 815 to 841.

Cure Violence, which inspired True 2 Life, is one of the leading non-governmental public health anti-violence programs. It was founded in 2000 by Gary Slutkin, M.D. in Garfield, Chicago. Called CeaseFire at that time, it reduced gun violence in West Garfield Park by 67 percent in the first year.

CeaseFire started their first hospital-based violence injury prevention program (HVIP) at Advocate Christ Medical Center in Southern Chicago in 2005. HVIP is a model for treating people at high risk for gun violence. Several trauma centers have developed violent injury prevention programs based in hospitals of neighborhoods that struggle with gun violence to meet the psychosocial, medical, and mental health needs of wounded patients that may lead to reinjury and retaliation.

As of 2016, CeaseFire is operating four centers in Illinois. The other three are in Northwestern Memorial Hospital, Cook County’s John Stroger Jr. Hospital and Mt. Sinai Medical Center.

This model spread from Illinois to New York City. True 2 Life, where Lopez works at, is based in Staten Island to serve the community.

“So basically, we get a call from the hospital while my manager will put it in a group chat and two or four people depending on who’s available, but always have to be pairs and we go to the hospital and speak to the patients and stop retaliation,” said Lopez.

Professor Jeffrey Butts at John Jay College of Criminal Justice argued this model is effective for two reasons. “When you have someone who’s just been shot, in the hospital being treated, the family and friends have gathered. If the anger is allowed to build and they know who the shooter was, that’s where people start to talk about getting retaliating,” Butts said. “So, if a hospital-based worker can be there and control that, the anger doesn’t get out of hand. That could really help prevent retaliations.”

The second reason is that the quality of medical care and the follow-up consistency can help prevent retaliatory shootings, because many retaliations happened because the injured person had not managed the wound properly, Butts said.

“They leave the hospital, they go home, they don’t change the dressing on the wound enough. They don’t do all the things that they were told to do. It gets infected, it gets worse, they lose a limb, they die,” said Butts. “The neighborhood hears that, and some friend of theirs want to express their anger and get back at the person.”

Another project collaborating with hospital facilities in Harlem and Central Brooklyn, Guns Down, Life Up (GDLU), was established in 2011. The project puts together hospital-based and community-based services and uses a community outreach network to share information about violence prevention.

The staff members of GDLU are called violence interrupters. Working within the community, they identify the high-risk people and resolve potential conflicts before they escalate.

One of the most direct ways to identify the potential conflicts is to get information about the story behind the shooting incidents. GDLU collaborates with hospitals to counteract retaliation when violence erupts.

Like the hospital responders at True 2 Life, the trusted violence prevention specialists at GDLU, called credible messengers, can enter NYC Health + Hospitals emergency departments after violent incidents and help stop retaliation and potential violence.

In collaboration with GDLU, NYC Health + Hospitals implements programs in facilities in Harlem and Central Brooklyn, such as Harlem Hospital Center, Kings County Hospital Center, and Lincoln Medical Center. GDLU regularly runs the prevention programs in collaboration with these health and hospital facilities.

True 2 Life’s prevention program is beyond the hospital. “Plenty of participants or patients that came down here asked for help and we have different offers, like Legal Aid or helping them with resumes. We have certain events, telling them to volunteer just to keep them busy out the streets,” said Lopez.

These prevention programs that use the Cure Violence model allow the practitioners to prevent gun violence by “attending to the victims of prior shootings, friends and family and their social networks,” said Butts. “You have to know who they are, where they hang out, and if one of them has hurt, you need to quickly go talk with the other members and basically persuade them that they’re going to get nothing out of a retaliation shooting.”

For Lopez, she has suffered the trauma of gun violence so she understands other individuals who need her help. Lopez has a been a cure violence practitioner since December 2017 at True 2 Life. After two years, she said, “I’m working here. love what I do. I’m passionate about it.”

How Social Media is Used to Tackle Gun Violence on Staten Island

Alpha Kamara

We understand the street language, we have been there before”

PARK HILL—Ten E-Responders sit behind their computers. They are logged on to their social media accounts. They are reading hundreds of messages and posts. They pay keen attention to emojis of well-known youths and social clubs in the neighborhoods of Park Hill and Stapleton.

They assigned themselves key tasks. Some on Facebook and others on Instagram and Snapchat. They don’t only read messages, but they also decode the tone and the looks on the faces of the photos posted online.

The E-Responder social media monitoring model was developed in 2016 by the Citizens Crime Commission and New York University’s Steinhardt School of Culture, Education and Development. The program’s aim is to monitor online behavior that has the potential of fueling street violence. The commission trained 26 groups across New York including True 2 Life, to be proactive in tracking the online activities of those potentially engaging in crime.

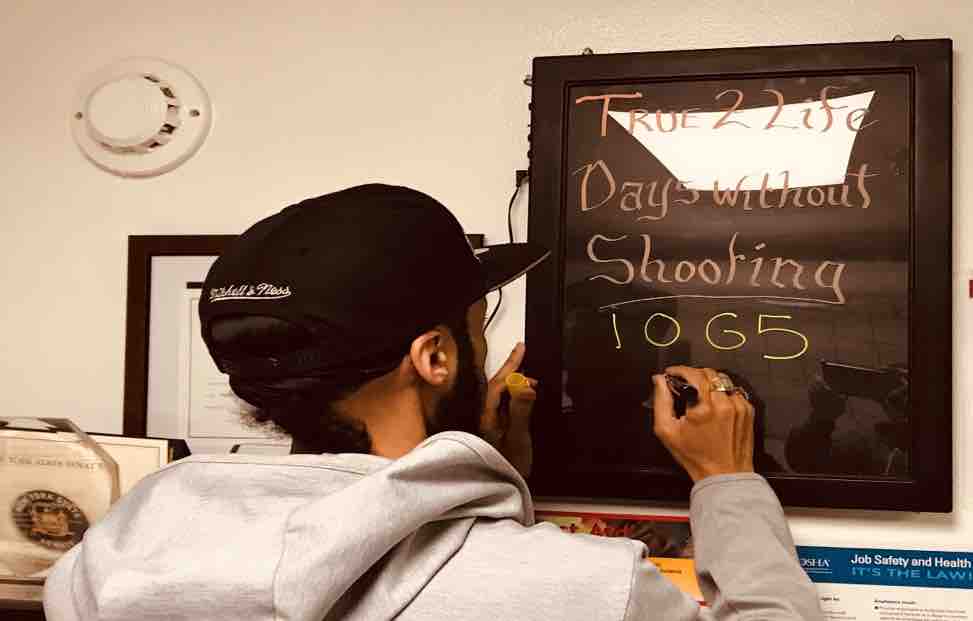

Mike stating on the board that they have not heard any shooting in Park Hill for over one thousand days.

“We dedicate two hours to this activity every day. We monitor and analyze violent or risky behavior online. It’s a key aspect of our campaign to end gun and gang violence in New York,” said Mike Perry, the program manager of “True 2 Life” Cure Violence in Park Hill and Stapleton, Staten island.

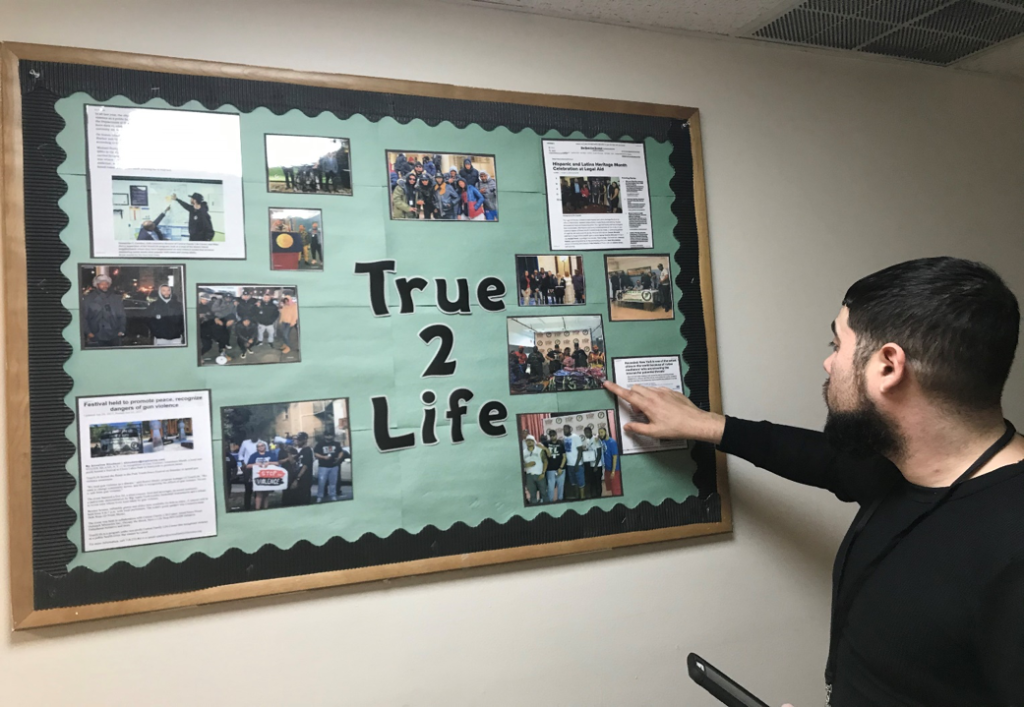

Santino pointing at their area of responsibility in Park Hill and Stapleton

With support from the Mayor’s office, True 2 Life Cure Violence program, monitors social media every day to identify posts and messages that have the potential to provoke gang violence or retaliation around the two neighborhoods in Staten Island.

Using Social Media to Fuel Gun or Gang Violence

According to a report from the Citizens Crime Commission New York, between 2014 and 2017, 200 cases of gun violence were documented related to social media posts. These are called cyber-banging by gang members in the country. Most of them were on Facebook.

The commission said however, there are far more cases than those presented in the report. “Our aim is to use this report as a way to not only track these incidents in order to prevent further social media-fueled violence—but also to encourage law enforcement to recognize and report such incidents, which we believe are woefully and dangerously underreported,” it said.

Policeone.com, a website affiliated with NYPD and the National Gang Investigators Association, said gangs use the broad reach of social media to recruit new members, intimidate rivals, promote criminal activities, advertise their brand, brag about to validate street credibility or dominance and violence.

The most popular platforms used are Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat and WhatsApp, the report said.

Several violent incidents recorded in the U.S. in the past have raised a red flag that social media needs to be monitored to avoid violence spilling over to the streets.

In 2017 in Chicago, Lamanta Reese, 19, was gunned down after posting a YouTube video disparaging a rival gang, which included an emoji that his shooter believed was an insult against his mother.

In 2014, the NYPD relied on one million Facebook posts in its largest recorded gang raid when officers stormed the General Ulysses Grant and Manhattanville houses in Harlem and arrested 40 suspects and charged them with 145 crimes of murder, assault, and violence conspiracy.

“We see cases of violent street gangs frequently; they’re bragging about what they do on social media. Our monitoring has proven to be an invaluable tool,” Dermot Shea, then the NYPD’s chief of detectives told CBS news.

An article published by the Daily news said that NYPD officers befriend some of the gang members on Facebook and monitor their activities and postings. It led to the arrests and imprisonment of over 40 members of the Washside gang, an offshoot of the Bloods that claimed control of some blocks in the Bronx.

Some critics however, questioned the action is not right because friends who had nothing to do with the incident were arrested in the raid.

True 2 Life’s Intervention

With these events and background, Perry and his staff said social media plays a critical role in spreading gun violence across the US. “Young people sacrifice their credibility, safety and morals for social media likes and fame. They can do anything on social media to attract crowd and intimidate their rivals”, he said.

Perry, a rehabilitated street gang member himself, lost his father through gun violence at 10. Nine years later, he lost his close friend in a similar incident. Those moments shaped his life to fight street crime and gun violence through, the True 2 Life Cure Violence campaign.

“When we see toxic language or emojis on line from a particular user, we can definitely spot the emotion and anger from the post. We move into action immediately with a direct message-like- yooo, what’s up? Halla at me. When he responds, we will find a time to meet and talk,” Perry said.

Street Language and Emojis with Codes

NYPD says they follow hashtags to spot organized attacks and grievances that are embedded in conversations, emojis and memes. But those types of engagements are difficult to understand without critical context, and understanding of the hyper-local language used.

But for True 2 Life, they understand the language of the street and it’s easy to spot an emoji or language that has a secret code.

“There are some words or emojis that have coded messages. You can read the post but can’t understand the language. But me and my staff have been there before. We can identify coded messages that breed hate or revenge,” Perry said.

“A common practice street gangs do to provoke a speedy reaction is wrapping and smoking stuff on line after the death of a rival gang member, he added. “It’s the highest form of disrespect in the street-he said. It means we are smoking your dead friend and you can’t do anything about it”. When we see that, we know it’s a red flag that something will explode if nothing is done.”

A team member is later dispatched to follow up on it until a settlement is reached.

True 2 Life staff are not new to street or gun violence. All of them are men and women who have been gang members one way or the other. They therefore understand the language and posts that have the potential to stir violent retaliation.

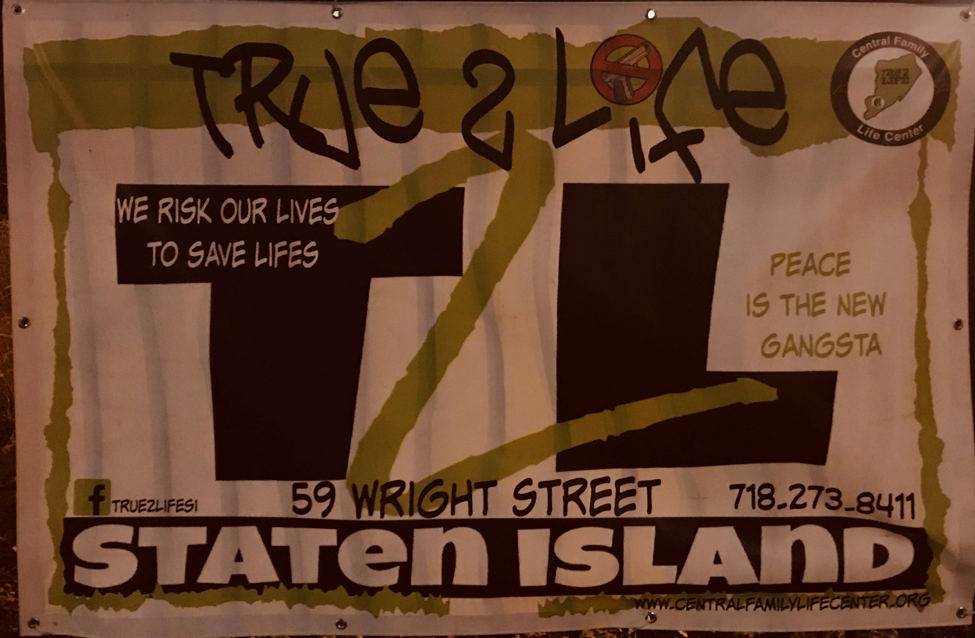

A wall paper of True 2 Life fixed along the street of Stapleton in Staten Island.

Santino Miranda spent over 15 years in the streets of New York. He survived a gun violence with a rival gang that tried to rob him. Street language and emojis are not new to him anymore. He said the gangs use emojis to pass on secret messages of intimidation.

He said if someone posts a demon emoji, it means he is thinking of evil because of a situation. It will likely lead to retaliation or revenge.

If someone writes “NO CAP-X,” he said, it means, he is not joking, he is ready for a revenge action.

If someone posts a gun online, it means it is loaded and he is ready to put a bullet in someone’s head. Ordinary citizens will never understand these messages. But my background gives me a clue of the situation,” he said.

Miranda said “If you live in a cool hood lane with Gs, they feel you in and out”-meaning, when you have integrity in the street, the street gangs will always have respect for you.

True 2 Life’s Timely Intervention

The interview with Miranda was interrupted by a Facebook situation. Someone posted a Facebook alert he needed to follow up on. “A friend selling (items) was harassed by a rival gang. They stole his items, beat him up in front of his wife and molested him. Some of his friends were angry,” he said. Miranda made few calls and scheduled a meeting. But he refused to speak in details on the issue.

A few weeks ago, the group’s immediate response helped avert a gun violence and retaliation that would have cost lives in the neighborhood. It started from an unusual Facebook post.

“A boy posted a picture with a gun on his lap on Facebook. We immediately contacted his dad,” Perry said. Together, we succeeded in convincing him to put the post down. We later realized he wanted to intimidate and retaliate on a rival gang member. We mediated between the two and ended the conflict peacefully. That stopped a deadly retaliation that would have cost lives.”

Doing this kind of work requires high credibility and trust. In the words of Perry, a credible person is one who doesn’t take sides. He keeps secret, truthful and doesn’t share sensitive street information with the NYPD. This is a key qualification of their recruitment.

“If you lose your credibility, you will not only lose trust, but you will also be putting your life in danger on both ends,” he said.

Challenges

True 2 Life E-Responders face challenges while doing this work. Their intervention is sometimes scrutinized by street gangs. For instance, when a post goes viral, it opens room for heated online exchanges, making it difficult to control.

“After a gang post goes viral, other actors involve will fuel the hate. The main party concerned now becomes reluctant to accept peace over the fear of been called weak by his friends. The focus will now shift to all other friends involved to accept. This can be very stressful and challenging,” Perry said.

Schneider Lopez is a hospital responder. She lived in the street for long. She survived gun violence after she was shot at a friend’s party. Schneider said gang members post their photos to provoke reaction and support from their friends.

“Some homies go on Facebook and post their reactions after an attack to provoke reaction. Some will even post their wounded faces. That alert will quickly prompt a response if not managed,” she said.

True 2 Life also uses social media to promote peace and highlight non-violence messages for feedback from the public.

Violent Social Media Behavior and Gun Ownership

Past hate-filled social media posts are getting more scrutiny. Suspects in several horrific mass shootings were found only later to have left social media hints of violence that went unheeded for years.

Now a New York lawmaker has introduced a bill that would require police to scrutinize social media and online searches of handgun license applicants, and disqualify those who publish violent or hate-filled posts.

“We certainly want to make sure we’re putting weapons in the hands of the right people and keeping them out of the hands of the wrong people,” said state Sen. Kevin Parker, a Brooklyn Democrat. He added he was inspired to act after the Pittsburgh synagogue shooting suspect left social media rants that Jews were “children of Satan,” he told The Washington Times.

But, True 2 Life is not against the right of citizens to own guns; their action is against the senseless use of guns by gang members.

“Listen, we are all going through the same situation, the same stress. Lack of jobs, poverty, illiteracy. Why should we hate and attack one another instead of supporting ourselves to change the big story?” She asked.

Two wrongs don’t make a right. Let’s put the guns away and the negative social media posts down and discuss as a family. “That’s why True 2 Life is here to support you,” she said.