Jamaica Rising

Jamaica, Queens in New York City is undergoing a transformation with new high rises and retail stores. Longtime residents worry that they may be priced out of a neighborhood that they call home.

Downtown Jamaica At Risk of Gentrification

Sabena Chaudhry

Downtown Jamaica is known for its mom & pop shops, family owned restaurants and single family houses. However, residents who have been living in the vibrant community for years are starting to notice changes such as big chains like Subway and Chipotle, high rise building developments, and a spike in rent costs.

New Yorkers sometimes joke that the arrival of a Starbucks is the first sign of gentrification. The first Starbucks arrived in Jamaica in 2016. The chain chose Jamaica to kick off its national initiative to uplift low income neighborhoods by opening Starbucks stores, the program’s first store opened on Sutphin Boulevard.

“Jamaica Avenue has always been an avenue known for small and family owned businesses when you see larger corporations come in like Starbucks, it’s alarming,” says Koshik Bhuyain, resident of Jamaica, Queens. “It makes you think this could have been someone else’s family business and now there is a corporation here.”

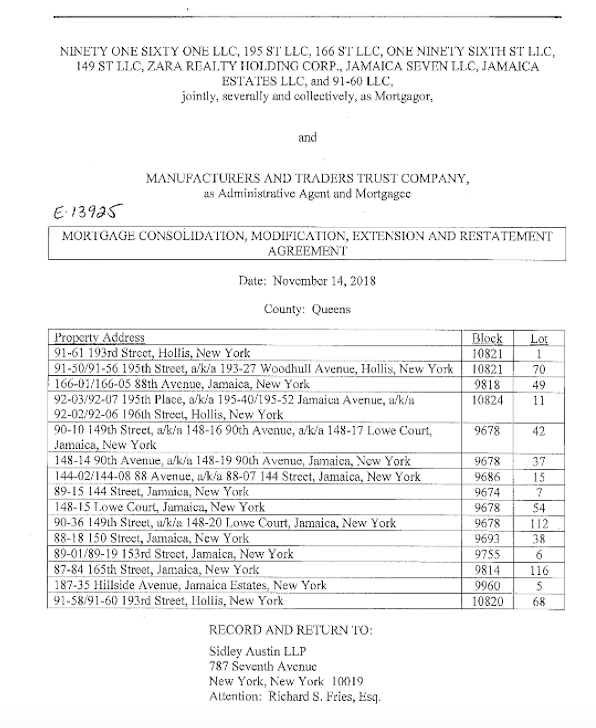

Zara Realty is one landlord that has built 40 apartment buildings in Queens, including dozens in Jamaica, making them the largest landlord of the borough. Since the 1980s they have been selling luxury apartments. “One sign of gentrification can be luxury apartments coming to an area,” says Dwanye Baker, Urban Studies Professor at Queens College.

All the changes has made some residents fearful that the soul of Jamaica will be lost because of gentrification. Over 60 percent of the population in Jamaica consists of African Americans, but transportation routes such as the LIRR, the E, J subway lines and Air Trains have attracted several immigrant communities to the area as well. “Jamaica has always been special to me. My neighbors are from everywhere,” says Courtney French, general manager at Jamaica Arts and Learning Center. “Living in Jamaica you can feel that the world can live together.” He added later: “Anyone wishing to gentrify the neighborhood should know many cultures have coexisted here for years.”

However, not all residents are viewing these changes as a problem in the community. “There is a Starbucks a few blocks away from me, so I am not complaining,” joked Tahera Akhtar, 22, who has lived in a single family home on Jamaica Avenue since 2006. “My sisters and I love going to the Chipotle on the weekend, so we don’t mind.”

In a gentrifying neighborhood, median income levels tend to shoot up. By definition gentrification is the “upscaling of a neighborhood which once was a place affordable to low income; now being replaced with higher income people,” says Dr. Melissa Checker, professor of Urban Studies at Queens College. The median income in 2016 for District 12 (Jamaica and Hollis) was $61,268, a 3.48% increase since 2010. Although the median income level is considered to be middle class, 14% of residents in the District are still living in poverty.

Jamaica was one of the many neighborhoods that fell under the city’s Inclusionary Housing Designated Areas program, passed in 2016. Under this program 30 percent of units are set aside for those whose income level falls below 80% of the Average Median Income (AMI) of the neighborhood. However, this program comes with an incentive for building developers. Buildings are allowed to increase their Floor Area Ratio (FAR), or the maximum amount of floor area allowable on a lot, allowing for buildings to expand resulting in more units.

Long time residents are noticing high rise buildings drastically changing the landscape of their neighborhood once dominated by single family homes. “The builders bought our neighbors house and now it’s a building. It’s kind of claustrophobic at this point because before we would have neighbors and backyard spaces. People would have barbeques. Now it’s just a lot of buildings and a lot of people coming in,” says Akhtar.

Tahera Akhtar’s family home crowded by high-rise buildings.

Although programs such as rent stabilization and inclusionary zoning protecting low income families are in place, residents are at risk of facing displacement pressure due to high costs of rent. Today, an average 1-2 bedroom apartment in Jamaica costs approximately $2,000, according to Zillow.

In 2017, Mayor Bill de Blasio made inclusionary zoning mandatory for certain areas that had been rezoned. Rent stabilization units protect tenants by placing restrictions on the amount a landlord can increase rent by. Earlier this year, de Blasio launched the Neighbor Pillars program, to protect neighborhoods that are “fast-changing” and where rent regulated apartments are at risk of turn over. The program seeks to build 7,500 affordable units throughout the city over the span of 8 years. However there are ways around it for landlords.

“You can’t just increase rent on rent stabilized apartments, so landlords tend to stop fixing things, turn the heat off, use intimidation and once that tenant leaves the [new] tenant doesn’t have to be rent stabilized,” says Baker. “That could lead to displacement pressure.”

There has been limited research published on displacement caused by gentrification since it can be difficult to track the number of people moving out of a neighborhood. “Displacement does happen if you look at it over a period of time. How can it not be happening? It’s not just housing that becomes unaffordable, it’s everything around. People can’t go to their cheap bodega, cheap Chinese take out restaurant, there’s so many aspects to it,” says Checker.

Jamaica is an area which has faced severe rezoning under plans such as South Jamaica Rezoning passed in the 2000s. These city policies allowed for greater density buildings to be built in the the zoned areas. “Rezoning and gentrification go hand in hand,” says Checker, “developers have been waiting for restrictions to be lifted in area.” There are not many situations where rezoning does not lead to gentrification.

The upside is that local residents are finding their community to be safer than ever. According to a study by NYU Furman Center the crime rate in Jamaica has gone down by 4.1% decrease since 2006. “My sister did not take night classes because she didn’t want to walk home alone at night and now I see people walking around the area at 11 pm, carefree,” says Akhtar.

There is still much debate about whether gentrification serves as a positive for any community. “Gentrification is inherently detrimental to existing neighborhood residents but if no displacement is happening and the neighborhood is just upgrading that means that property values are increasing, causing an increase in property taxes which leads to street lights, police protection, etc. Increased taxes go back into the neighborhood and that is positive,” says Baker.

Positives still come with risks. “Problem is,” warns Checker, “it’s for new people not the older residents living there.”

Investing in Jamaica

Emily DeLuca

This interactive map shows the fifteen buildings Zara intends to invest in the coming years. Each icon shows the number of units, block number, lot, the number of formal complaints, building & environmental violations, and any upcoming construction plans filed for this year.

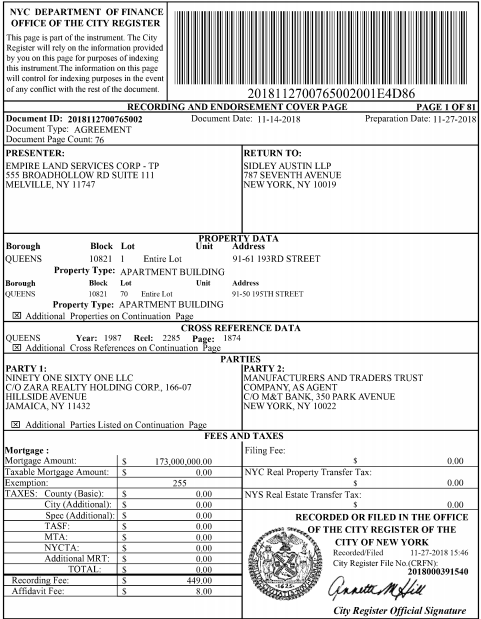

Zara Realty receives $173 Million Loan: what will this mean for tenants?

Zara Realty received a $173 million mortgage loan from M&T Bank on November 14, 2018. According to a statement issued by Zara Spokesman Jason Fink:

“We are making long-term investments in our buildings in Queens, modernizing and improving critical infrastructure and adding amenities for our tenants.” Such investments could include upgrading heating and cooling systems, installing new elevators, new roofs, gyms, new hallways in common areas, as well as renovating kitchens, bathrooms and flooring in individual units, according to the statement.

The main concern among tenants is whether or not these renovations will qualify Zara for an incentive called Major Capital Improvements. If they do qualify then Zara will be allowed to increase the regulated rent prices on all of the tenants living in the rent stabilized buildings. According to the Urban Justice Center almost all MCI applications submitted to the DHCR are approved,

“The vast majority of MCI’s are approved even when its not clear that the work was a renovation rather than a needed repair,” says Jonathan Cohen, the director of legal services at the Urban Justice Center’s Safety Net Project, a project that fights for the protection and rights of tenants.

“In some cases a landlord can allow certain aspects of a building to deteriorate and then come in, do the work and get a permanent rent increase from every tenant in the building for what should be properly characterized as a repair rather than a renovation.”

OBTAINING AN MCI

If a developer wants to obtain a MCI they have to get the construction improvements approved by the Division of Home and Community Renewal (DHCR) and lay out all their construction plans and costs in their RA-79 form. According to the DHCR, owners can qualify for Major Capital Investments if they meet a number of qualifications such as:

- Be depreciable pursuant to the Internal Revenue Code, other than for ordinary repairs.

- Be for the operation, preservation and maintenance of the building.

- Directly or indirectly benefit all tenants.

- Meet the requirements set forth in the useful life schedule contained in the applicable Rent Regulations.

Landlords can only apply for a MCI within two years after the construction has been completed. Since this $173 million loan has just recently been awarded, Zara will have to complete all of the proposed renovations before filing a MCI with the DHCR. If Zara does file for a MCI in the coming years, tenants can access the MCI and all the details of construction and costs by filling out a request form with the DHCR.

If tenants are afraid of a MCI rent increase they should keep a visual and written record of all the construction improvements that are being made to their building.

TENANTS

Tenants can fight a MCI increase and hold landlords accountable by collecting evidence and presenting a case to the DHCR when the MCI is filed. They have 35 days to submit an appeal to the DHCR once the MCI has been issued to the tenant. Issues that the tenant can track and present as evidence are not limited to the following.

- The work doesn’t benefit all tenants or doesn’t benefit the whole building. For example, the windows were only replaced on the third floor of a six-floor building.

- The work was not necessary and is cosmetic in nature only.

- The building owner did not properly document costs or did not properly calculate the costs.

- The building owner has harassed tenants. See DHCR Fact Sheet #17 available here for further information and file a report if necessary with DHCR.

- The owner’s MCI application was filed more than two years after the work was completed.

- Owner did not obtain the appropriate approvals from the local municipality as required by law.

- Owner received a government grant or insurance proceeds to pay for some of the work.

For a complete list go to DHCR page.

Jamaica Queens is changing and luxury apartment buildings are on the rise. Zara Realty is leading the way for these investments and with this new loan Zara will dominate the development scene in Jamaica. Landlords argue that MCIs are necessary to protect their investment and ultimately to ensure a profit. Without them, landlords warn, the city’s aging rent stabilized housing stock is at risk of suffering as it did in the 1960s and 1970s when deteriorating buildings were abandoned.

“Unless you invest and put in new boilers, new elevators and continue to use capital dollars you’re going to relive history all over again,” says Joseph Strasburg, president of the Rent Stabilization Association, a trade group that represents landlords. With these MCI renovations comes the decline of original rent stabilized units in NYC which has seen overall net loss since 1994.